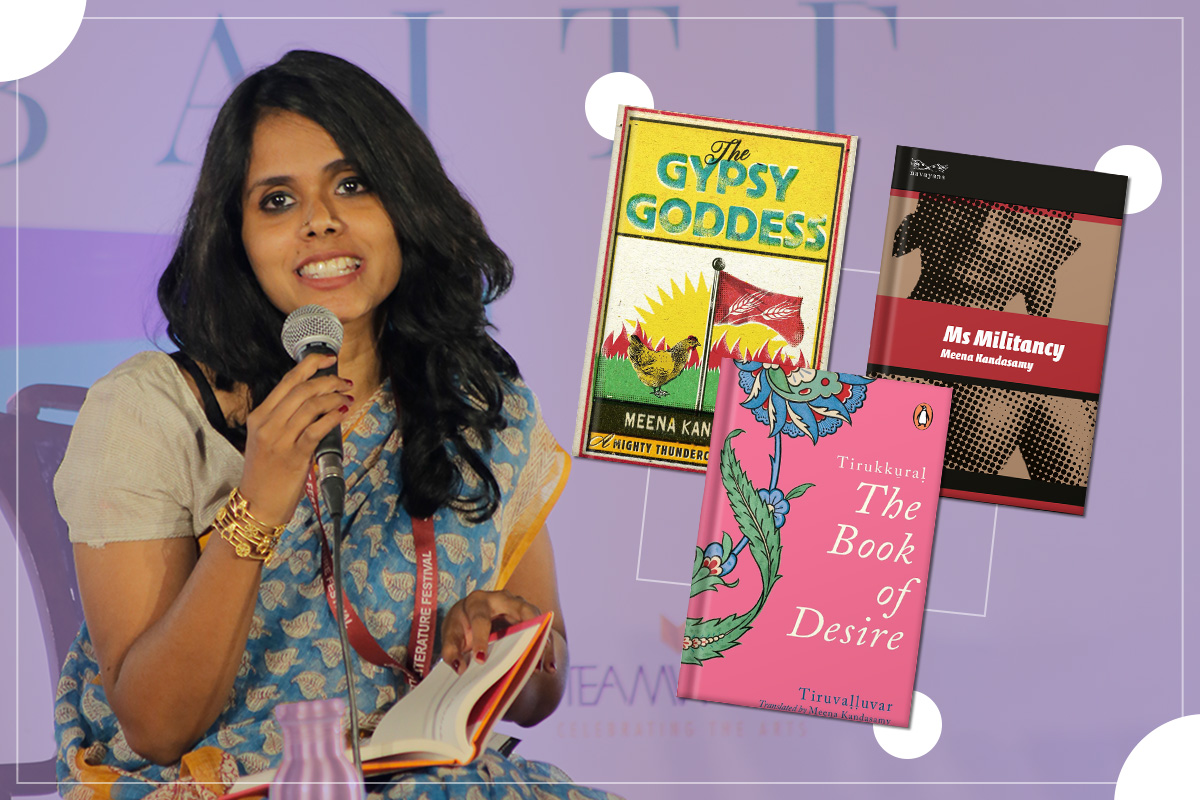

At JLF 2023, Kunzum sat down with poet Meena Kandasamy to discuss her latest book—a feminist translation of a Tamil classic—her tools of activism, artificial intelligence, her next poetry collection, and the writers and books that have shaped her craft. By Sumeet Keswani

Meena Kandasamy wears many hats: poet, fiction writer, activist, translator. At the recently concluded Jaipur Literature Festival 2023, Kandasamy spoke at length with Manasi Subramaniam, Editor-in-Chief of Penguin Random House India, about her newest work that actually dates back 2,000 years! It is an English translation of Tirukkuṟaḷ, commonly shortened to Kural, which is a classic Tamil-language text composed of 1,330 kurals (couplets). Kandasamy’s translation is titled The Book of Desire, aptly so since her intervention—she’s only the second female translator of the text—frees the female lover in the Kural of the male gaze typical to other English translations and gives her back the agency and desire the original text intended.

Kunzum had a lovely chat with Kandasamy on a wide range of topics, from the powerful influence of a good translation, to AI and social media, activism and accolades, and her next poetry collection (coming out this May!). Excerpts below:

A Conversation with Meena Kandasamy

Kunzum: Your latest work is an English translation of Tirukkuṟaḷ (The Book of Desire). And you’re famously only the second woman to translate this 2,000-year-old text. How much influence does the translator have over a classic that’s composed entirely of couplets?

Meena Kandasamy: This is very interesting. I think the translator has enormous power—not because we’re going to do something wrong [with the text], but because we’re going to correct some mistakes that have happened [in the past]. The original book speaks of love, of one lover who’s male and another who’s female, but apart from this basic gendering, it doesn’t say anything more. But in almost all of the translations, they’re shown as husband and wife; the idea of marriage is foisted on them—it doesn’t exist in the [original] text.

Also, none of us know how marriage existed 2,000 years ago. We don’t know with any clarity what its form was, what it meant, what the rules were. There’s this concept of nirai, which means ‘fullness’ or ‘self-containment’ in Tamil, but somehow all the male translators—not just the English translators but also the Tamil commentators—have decided to translate nirai as chastity, purity, virginity. The idea here is to reclaim what the text [really] is, not about inventing a new text. All I’m saying is: read the text without imposing masculine prejudices, without patriarchal constructs.

Kunzum: You spoke in your JLF panel about how the original text is omnipresent, for instance, in school assemblies where schoolchildren recite it. You, too, learned it by heart as a kid, thanks to your father. When did you realise that the translations had these imposed meanings?

Meena Kandasamy: When I was young, I didn’t do much research, obviously. Then I started writing poetry in my early 20s. I started translating some of this [text] because none of the translations were capturing the [true] meaning and I was dating people who were not Tamil—I wanted to send them a translation. So, I started doing little translations for myself. That’s when I realised that at some point I was going to do it. I’ve been with this book for 10 years because I do a little translation here and there but I’ve never done it full-time, and then, the pandemic happened. I was in London, and there was a really difficult lockdown. So I moved back to India with my two children. When you have small kids, it’s very difficult to work—to sit and write a novel. So, Tirukkuṟaḷ was an easy thing to do: it’s really short and crisp. It’s a very ‘pandemic work’.

Kunzum: You’ve also talked about how social media-friendly these couplets are. Instagram poetry tends to be short and often bereft of depth by design—to appeal to short attention spans. Do you think any of these platforms pose an existential threat to the craft of poetry?

Meena Kandasamy: Poets have been trying to kill poetry for thousands of years. So, I never think anything is a threat to poetry. And I think new formats always give rise to new ways of writing and thinking. I’m very technology-friendly—I don’t do Instagram poetry, but a few weeks ago, there was all this craze about ChatGPT so I wrote a short story collaborating with ChatGPT. You have to use everything at your disposal, whether it’s AI or social media. All of this has to coexist with art, because art is always one step ahead of innovation. There are so many ideas that are thought about in the world of art before they’re translated in the world of science.

Kunzum: I actually read your collaborative short story with ChatGPT. What did you make of your conversation with the AI?

Meena Kandasamy: A lot of the times, those of us who are in the social sciences are very suspicious of machines. Most of us are very suspicious of new technology. And a lot of the press I see around AI comes, of course, from a place of concern—that AI is racist, for instance, in terms of facial identification, or that a certain AI listens more to men’s voices than women’s voices. But it’s very easy to fall into this trap of thinking. When I was asking ChatGPT questions about regime overthrows and dictatorships, it worked on data [for its replies]—and data is history. From history, AI cannot introduce any of its own biases. So, everything it pulled out is what a left-wing intellectual will tell you: that Turkey, Egypt, and the Soviet Union are bad examples. It also has an endless memory, so, for me, it was amazing! If I said this, or you said this, we would be seen as people with biases. But here’s a machine that’s telling us something based only on data.

Kunzum: Talking about speaking up, congratulations on winning the Hermann Kesten Prize! What does a prize like this do to you—does it pose more risk to your activism or does it immunise you to some extent with its international limelight?

Meena Kandasamy: It’s a very intelligent question to ask. I was very, very torn about this prize. The first instant, when I got the prize, I thought it was a trap—like what happened with Nidhi Razdan. So, I did not believe it’s true—even when people started talking to me about it. Then it appeared in the Zeit, the German newspaper. That’s when I knew it was real. Until then, I didn’t even tell my parents. The second question that came to me: on the one hand, you feel so exposed—nobody consults you before giving you a prize, and unlike a lot of people who raise their voice, I live in India—but on the other hand, any international exposure is good, it’s a safety net. So it gave rise to mixed feelings in me.

Kunzum: And did the prize affect your choice of literary projects?

Meena Kandasamy: No no no… I just felt pissed off for like five seconds. (laughs) You know, when you’re a writer everybody has this idea that you should be winning writing prizes. And I won a prize for writers who are activists. People in India have a tendency to dismiss you as an activist and not look at how literary your work is, and I often feel that when you’re an activist you have to be far more literary, far more beautiful, far more persuasive, far more seductive, far more intellectual, otherwise you’re easily dismissed.

Kunzum: Let’s go back to the beginning for a bit. You started writing poetry at a young age, and later fiction. What makes you choose poetry as your main tool of protest as an activist?

Meena Kandasamy: I started writing poetry when I was very young. But I always wanted to write fiction, because, for me, fiction is like being in a large house and having control. You have so much room to move, and the reader is living in there with you. Whereas poetry is something you can do on a stage—you get five minutes to convince them. There’s also a difference in how you live. When you’re young, you have a lot of time. I wrote a lot of fiction between 2009-10 and the time I had my first child. But afterwards I didn’t have much time, so I returned to poetry; time is very fragmented for me [today]. It’s also the political climate. You cannot expect to have a book out every five years with ideas that challenge fascism. If the fascists are on Twitter, you have to be on Twitter as a writer. You have to be where the people are. You can still do the slow, long-form literature, but you also have to respond. You have to adapt to the changing times. My new poetry collection is coming out this May after 12 years. It’s called Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You. I think it really speaks to our times.

Kunzum: Which book would you recommend as essential reading to our community?

Meena Kandasamy: The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, Annihilation of Caste by Dr Ambedkar, The Autobiography of Malcolm X—these are books that fundamentally changed me. [In terms of poetry] The poetry of Sylvia Plath, and Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky.

Kunzum: Which writers have had the most influence on your craft?

Meena Kandasamy: I love Kamala Das—the way she allowed Indian phrases and sounds to enter [poetry]. My poetry is heavily influenced by her, both in theme and feeling. I love Arundhati Roy, but I don’t write like her at all—something that happened to young women writers was that everybody started saying, ‘Oh you’re trying to be an Arundhati Roy’, so you tried to style yourself differently. But I love her work. I also love Roberto Bolaño and Gabriel García Márquez. These are writers whose style I like a lot. Also, Nabokov! He’s a great stylist, nobody writes like him.