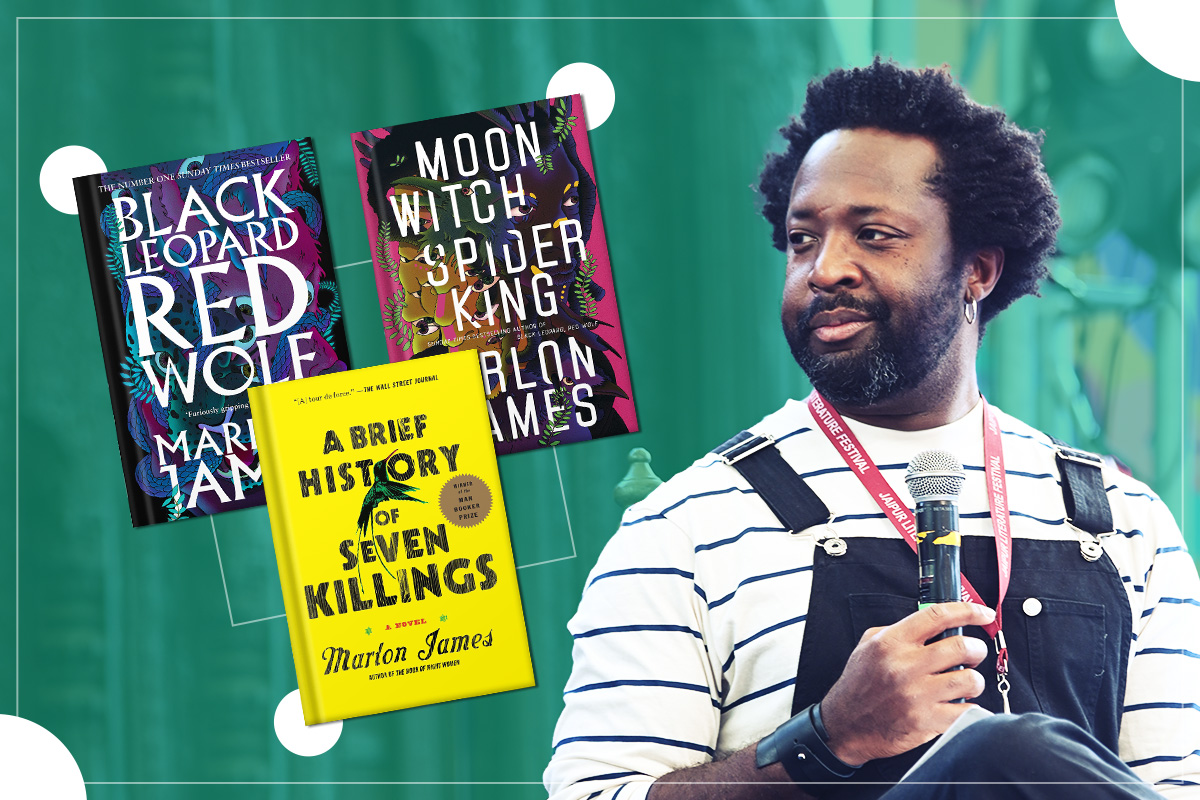

Winner of the 2015 Booker Prize, Marlon James, was one of the many acclaimed speakers at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2023. We spoke with him about African myths, unlearning Eurocentrism, his book recommendations, and the upcoming third book of his Dark Star trilogy. By Paridhi Badgotri

Marlon James charms you with his humour and easy smiles, but his books are the opposite of his personality―their violence leaves you disturbed and terrified. His Booker Prize-winning novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings, explores the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in the late 1970s and what it meant for Jamaicans. With over 70 characters—all written in first-person—James tells a story that is full of perspectives. His latest fantasy trilogy follows a similar rhythm. He tells the same story in each book of the trilogy but in three different voices—a character from the first book becomes the narrator in the next one. James’s explanation: in African myths, a trickster narrates the story, and you can never know the truth.

At the recently concluded Jaipur Literature Festival, James was engaged in a fascinating conversation with Age of Vice author Deepti Kapoor. Later that day, we sat down with him for a dialogue on his books, characters, use of language, African myths, and much more:

A Conversation with Marlon James

Kunzum: You once said that you are not a writer but a journalist for your imagined people—but you also write in first person. How do you maintain the distance that journalism requires while also becoming the voice of your characters?

Marlon James: I will get into the second part of the question first. I have to sort of sit down and spend the day with these characters. So, I spend a lot of time not-writing, and I’m just trying to hear a voice and then maybe I’ll write a paragraph―and that turns out to be the wrong one―or I’ll start with five pages straight. And by themselves, they’re worthless, but in terms of pointing out where to go and where not to go, they can be really, really useful. You have to get to the point where you can embody the character, or if you can’t embody them, then at least observe them as a journalist—as a competent journalist. There are writers I know who would never score points for personal empathy, certainly not as people, but their eyes are sharp and they pay attention. As for the distance, I teach a lot of memoir [writing] and personal essays, and a lot of things that I have to remember and teach others is [that] you have to turn yourself into a character. So, there’s a narrative self and there’s a reflective self, and both of them come together to tell a story. But sometimes, one of them has to dominate. If the reflective self dominates, then you’re going to give a lot of opinions and an alternative story. And yes, first-person is ultimately somebody’s opinion but a story has to be more than that. What if a character is unreliable? So the character has to give enough objective detail that you believe the world you’re talking about, regardless of the character being biased… Again, I don’t necessarily write them as characters but people, and they see things in a certain way, so I just have to remember all of that. I also have to remember to be humane with these characters, especially because they do some terrible stuff sometimes. And even then, I have to remain humane and consider all the aspects of a character.

Kunzum: Does this journalistic view of literature come from Marquez?

Marlon James: Yeah, because he was a journalist. And to me, the journalistic side and the magical realist side are not separate—because of the world he is writing about. The world I’m writing about, the world Deepti [Kapoor] is writing about [in Age of Vice], the world Roberto Bolaño writes about—and I’m not saying that I am as good as Marquez or Bolaño—but that we come from worlds where reality is wilder than fiction. Mexico is crazy. Philippines is crazy. Mumbai is crazy. And everybody else is thinking it’s too fast but no, that’s just the world we live in. I had a student from Mumbai and he was talking about how noise comes right in [his home], and I’m like, “Dude, I know what you’re talking about. Whenever I open the window, I can hear traffic.” And that’s our reality, our normal, but we also feed on it. It’s our energy. We need [that] energy because they are the worlds we write about.

Kunzum: I know what you mean. When I went to Edinburgh for a year, the silence terrified me…

Marlon James: Yeah, I can’t do it. My boyfriend likes silence, and he goes away to writing retreats. To me, silence sounds like deafness. I rarely go to residences, in fact I am resistant [to residencies]. I finally went to one, and I kept it short. It was supposed to be a month, but by the third week, I was like, “I’m done. Cannot do this!”

Kunzum: Going back to Marquez, does the Dark Star trilogy have a touch of magical realism?

Marlon James: I think it does. I could have easily said it was a magical realist trilogy. I don’t know about here but certainly in America, the UK, we still have these categories that we impose snobbery on. So Margaret Atwood is magical realism. Ursula K Le Guin is sci-fi. And therefore, Margaret Atwood must be a better writer—of course, Margaret would be outraged by such a statement because she certainly wouldn’t believe it. But that’s where we are. I could have easily said the trilogy is speculative fiction because I’m a “literary fiction” author, but I am [actually] writing a fantasy novel. It’s a little ridiculous when people think it’s a lesser genre. All storytelling comes from myth-making. [When] We want the really big answers, we go back to our mythologies or we make new ones. So, there’s something fundamental about this kind of storytelling that, I think, makes us human. So yeah, I don’t shirk away from that term.

Kunzum: While we’re on myths, you’ve talked about unlearning European myths and celebrating your own. What kind of challenges did you face in doing this?

Marlon James: Well, the problem in unlearning is that I am still writing in English. You know, some people think you can’t use the master’s tools to dissemble the master’s house. So I’m like, I am not trying to dissemble a house so much as I am claiming it. I don’t think anybody owns the English language. And I have to remember that, because that is not the way in which I learned English. I learned English in a very colonial way. And the problem with Jamaican English—and a lot of Commonwealth English—is that we all sound like a butler. We were taught how to serve English; we weren’t taught irony. The British would never have taught us irony ’cause then we’d laugh at them. But I had to realise that there is no such thing as ‘standard English’. No culture owns it. Honestly, if it wasn’t for Irish, Indian, and Caribbean people, I’m not sure we’d have an English language now. One was the idea that I was serving language and something that is an exalted thing that we should approach with kid gloves. I’m like, No! Use it, abuse it, violate it, bring in other languages, you know, realise that your dialect is on par with your so-called standard.

Kunzum: Yes, I think Indians, too, are obsessed with the structure of ‘standard English’ and its correct pronunciation.

Marlon James: It’s okay to learn structure if you want. It’s not necessary whether you learn the idea of proper English, [because] it’s just a tool. If you want to learn so called ‘standard English’, then fine, it’s useful. But I think we still look at the language as something aspirational. Like you’ve accomplished something if you can speak properly. And what does that mean anyway? You know, one of the funny things about British English is that they’re so obsessed with dip-downs, like you know someone is talking in British English when they put vowels that are not in the world. You know, “book” has two Os, not 15. Have a British person say ‘W’ and ‘R’ at the same time—they can’t. It’s always S-I-R, but it’s S-O-U-R. That’s just the centricity of British English, and they have tons of them. Nobody owns English anymore. Nobody owns language. The second people start to own languages, that second they kill it. And I think when we realise that, we realise just how powerful it can be and also that we can communicate in the languages we have. I think it’s upto us to take some more time. Instead of telling somebody, “Well, you need to start speaking in the English English,” maybe spend some minutes and learn Indian English. Or listen more clearly, or listen deeper.

Kunzum: One of the things that you found in the research for Dark Star trilogy was that African myths celebrated gender fluidity and had they/them pronouns but none of it survived colonialism. The same thing happened in India—we also have gender-fluid figures in our mythology. Why then is the West seen as more progressive?

Marlon James: I mean, one reason is the penal codes. Britain repealed a lot of the penal codes, but they never did it in the Commonwealth. No wonder there are homophobes in the Commonwealth. The thing about the British attitude towards repealing laws is the idea that we have now become so sophisticated, [that] we no longer need this law. Britain didn’t apply that sense of sophistication to the colonies, because they didn’t think we were sophisticated enough for the repealing. And because of that, the laws remain. I think, because a lot of these societies come from particularly non-British, non-Christian, non-Calvinists, the idea of gender fluidity is, funnily enough, one of those things that go through almost every culture. People think this is a new thing. I got news for people. You know, for some of my friends, Black friends, it is so easy to call somebody “them.” There are Native American societies with 14 genders. So, I think—and this is what research showed me—that’s how we always were. People think that society has accepted it now but we were born ready―until a bunch of European religions and European Pope told us we weren’t. If anything, it’s not even an unlearning. It’s a relearning of what we have lost.

Kunzum: What can we expect out of the third book of the trilogy?

Marlon James: Well, if I’m going to tell you that, I might have to kill you. I mean, I can tell you the name of it but I don’t think the name is a secret. The name is White Wing Dark Star, and you can use that title to guess who would tell the story.

Kunzum: Can you give us five book recommendations from your recent reads?

Marlon James: John Wray has a book coming out called Gone to the Wolves. And I really like it because it’s very hard to capture rock-and-roll in a novel. That novel is the first one I’ve read about heavy metal, and even if you’ve never cared about heavy metal and will never listen to a heavy metal record, I think it is very important to look at the wasted youth and why a person, who is born with no prospects and almost no future, turned to music―and when is it constructive and when does it become destructive. I’ve been thinking about Roberto Bolaño’s By Night in Chile. It is one of his shorter novels but may still be his best book. I also really like Arabesques by Anton Shammas. I just read Giovanni’s Room [by James Baldwin] shockingly. I’m so glad I read it now. I couldn’t have read it when I was 17—I would never have finished it. I identified with it too much, and it would have been very painful. Oh and Mrs. Caliban [by Rachel Ingalls]. A lot of people thought The Shape of Water (the movie) stole the idea from Mrs. Caliban, and maybe it did―I don’t know. But it is, you know, bored-housewife-falls-for-a-sexy-sea-creature and that’s all I’m gonna say about it!

Kunzum: Which authors have influenced you the most?

Marlon James: I mean, every author influences me, and I read a lot when I’m writing. I also find it funny when people say they don’t read when they’re writing ’cause they don’t want to be influenced. I’m like, man you can only hope! I love being influenced! I still know the first long paragraph in Black Leopard Red Wolf happened because I was reading Kate Tempest’s novel. And I loved how near the beginning of her novel, a sentence is not even a run-on sentence but a sentence that runs away with itself, and I’m like, I want to do that. I know which parts of Brief History [were formed] when I was reading Mrs. Dalloway. So yeah, I’m constantly inspired from whoever I’m reading.

At Kunzum, we have many of Marlon James’s books available across stores. You can browse our extensive and thoughtfully curated collection by walking into our bookshops, or place an order by sending a WhatsApp message to 8800200268.

Related: Every Obituary Is a Hurried Piece of Literature: Anees Salim