Online retailers offer heavy discounts but they can never replicate the experience of browsing a bookshop and finding a book you did not know you needed. A Kunzum bookstore helped a fan of Sylvia Plath discover a hidden facet of her life: drawing. By Sumeet Keswani

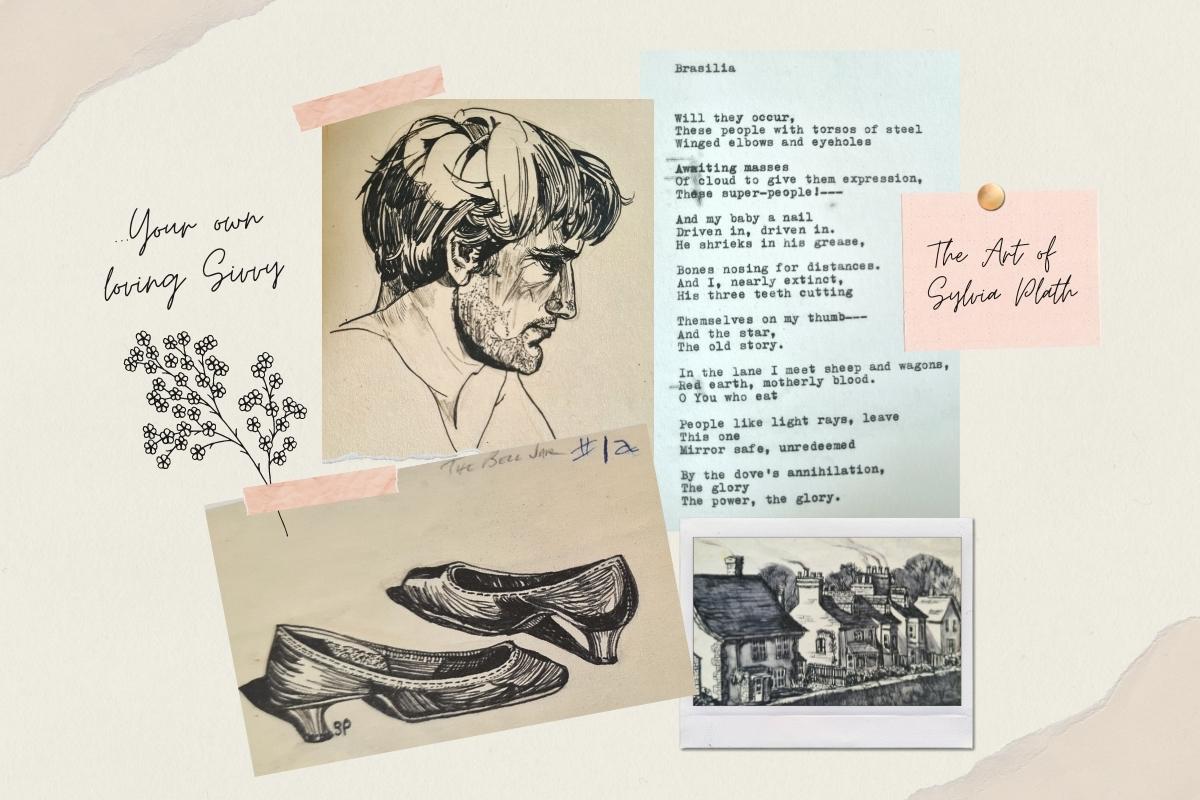

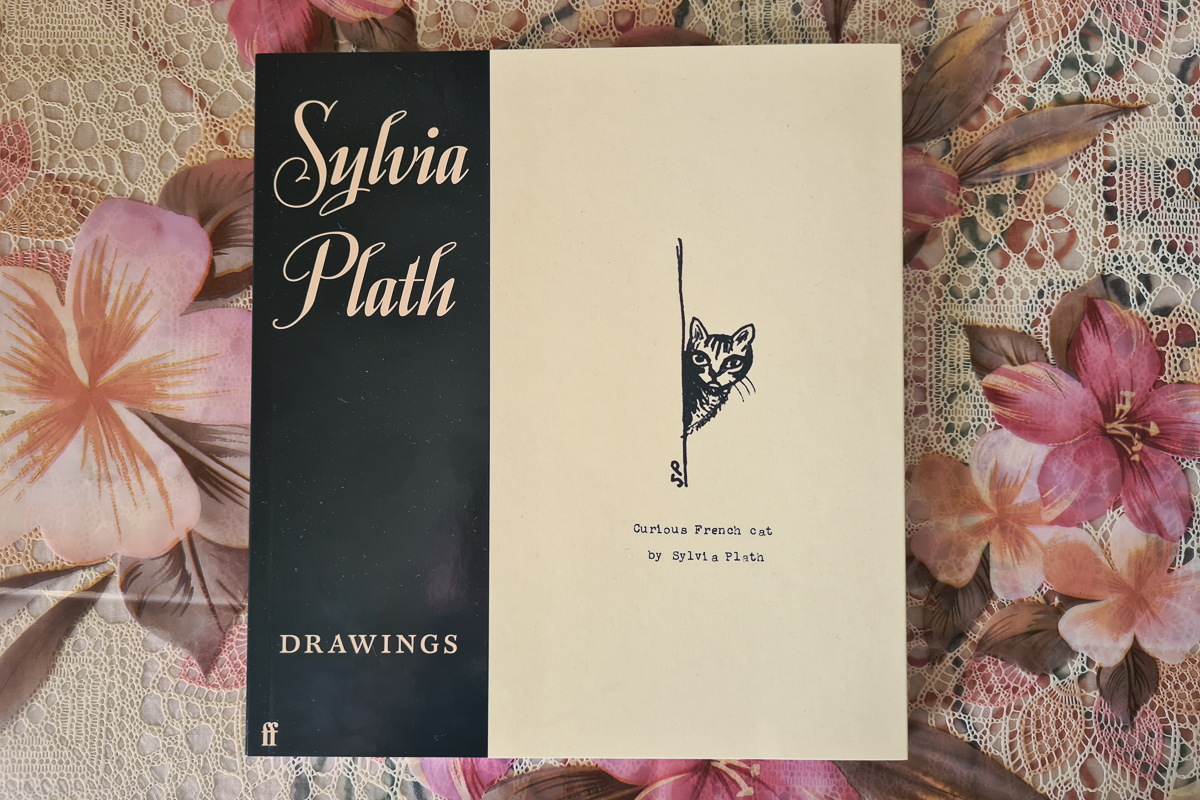

I have an unhealthy obsession with Sylvia Plath. I’ve consumed her writing in almost all its forms: not just her semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar, which resonates with women and readers struggling with depression all over the world, and her Selected Poems, infamously edited and arranged by her estranged husband Ted Hughes, but also her letters, journals, and short stories, which make up the books Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams and Mary Ventura and The Ninth Kingdom. So, I was thrilled to find a new form of art that I didn’t know Plath had practised in her short but trailblazing life. At Kunzum Vasant Vihar, on the shelf behind the billing counter, Sylvia Plath: Drawings sat innocuously—a ‘curious French cat’ inked on the cover—alongside graphic novels by Joe Sacco and Guy Delisle.

This rare book features a collection of Sylvia’s drawings (from England, France, Spain, and the USA) that Ted Hughes bequeathed to their kids, Frieda and Nicholas Hughes, before his death in 1998. Most of them are from 1956-57 and find a mention in Sylvia’s journal entries and letters—to Ted and her mother—but some are undated. The said letters and journals accompany the drawings in the book for context.

In the book’s introduction, Frieda Hughes objectively states the history behind this work, inevitably touching upon the dual tragedies of her mother’s and brother’s suicides, without letting emotion getting in the way. Perhaps she wants all the sentiment to come from her mother, who felt everything intensely and poured it out in her work. Or, perhaps, an introduction isn’t enough space to talk about every emotion stirred up by revisiting her parents’ lives and work—a subject of epic debates and almost lore.

Copyright: The Estate of Sylvia Plath

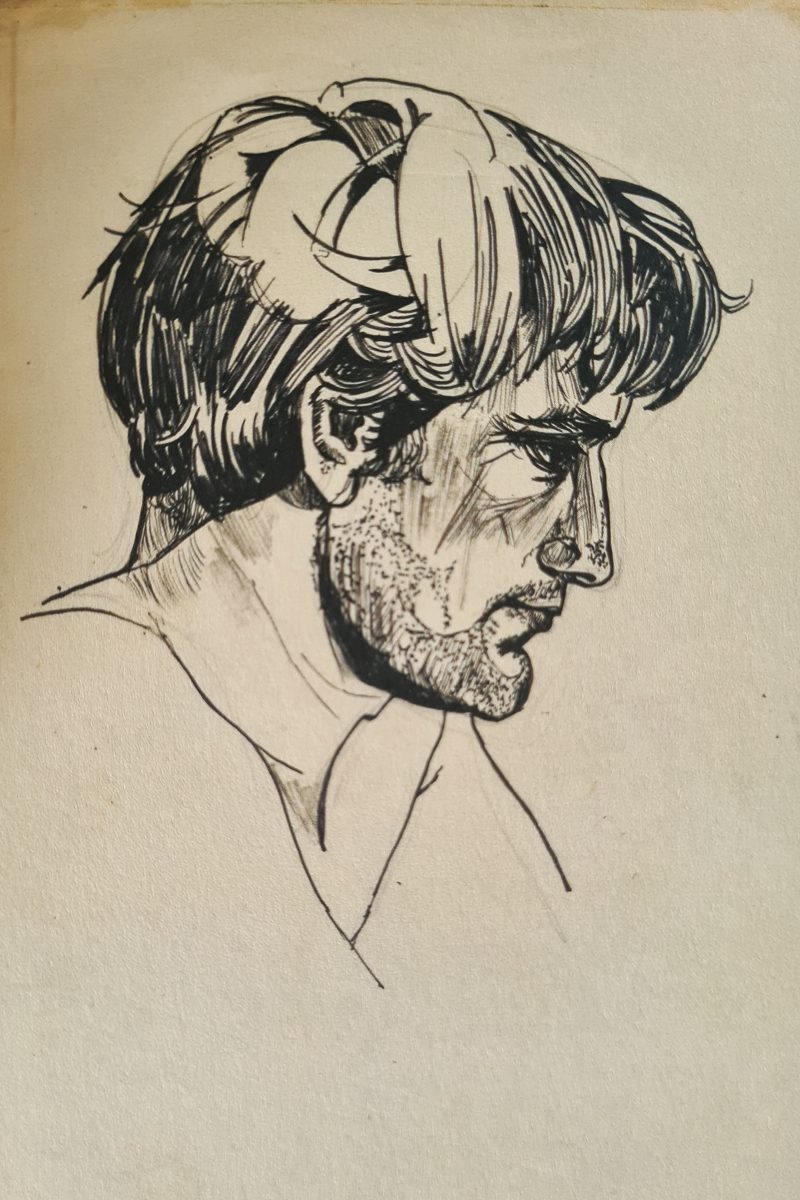

The drawings themselves are surprisingly strong in technique and unsurprisingly meticulous. In a letter to Ted Hughes dated October 7, 1956, months after their secret June wedding and during her study at Cambridge University, Sylvia describes a day she spent drawing bulls while sitting amid cow-dung on the Grantchester Meadows. The act of drawing gives her peace, she says, a state she relishes as a reprieve from the violent longing she feels for her new husband during this period of self-imposed separation.

Copyright: The Estate of Sylvia Plath

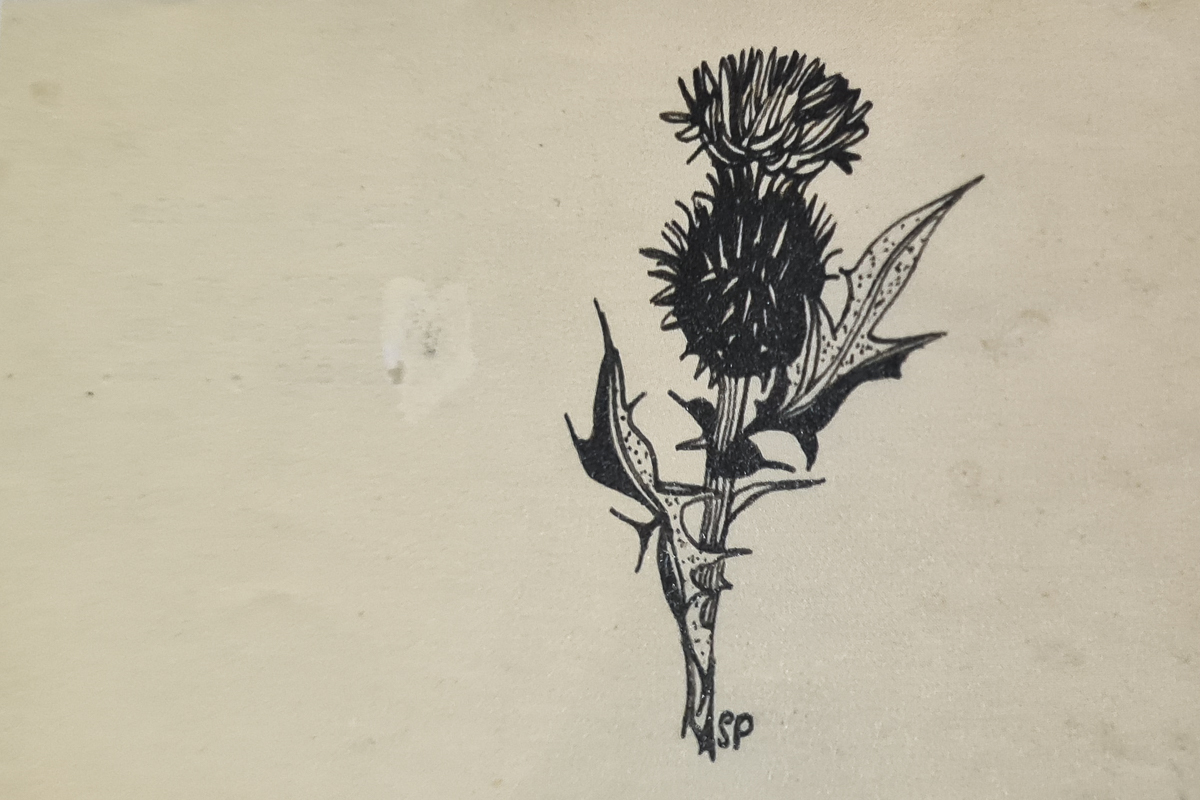

Sylvia loses herself in drawing; in fact, it gives her more peace than prayer or walking. And so, on one of her walks she collects a purple thistle and a dandelion cluster, and sits down to draw them in loving detail. But true to Sylvia’s nature, even her drawing comes with unbridled ambition. She wants to send “a sheaf of stylised small drawings” of everyday objects to The New Yorker in the hope that the magazine will publish them among the illustrations that break the monotony of its articles. In her private journal entries (The Journals of Sylvia Plath, Faber & Faber), she acknowledges her “dreams of grandeur” about the magazine using her illustrations with her own written work some day.

It turns out, there’s a whole book of them today.

Copyright: The Estate of Sylvia Plath

In letters to her mother, Sylvia expresses pride in her evolving art of drawing, asserting that the ones she has made in Benidorm (a Spanish town where she and Ted spent five weeks of their honeymoon) are the best she’s done in her life. She credits Ted for encouraging her practice and is later thrilled at getting four of her Spain sketches published—along with an article—in The Christian Science Monitor for £9. She urges her mother to “get lots and lots of copies of each article,” reinstating that the sketches are “very important” to her.

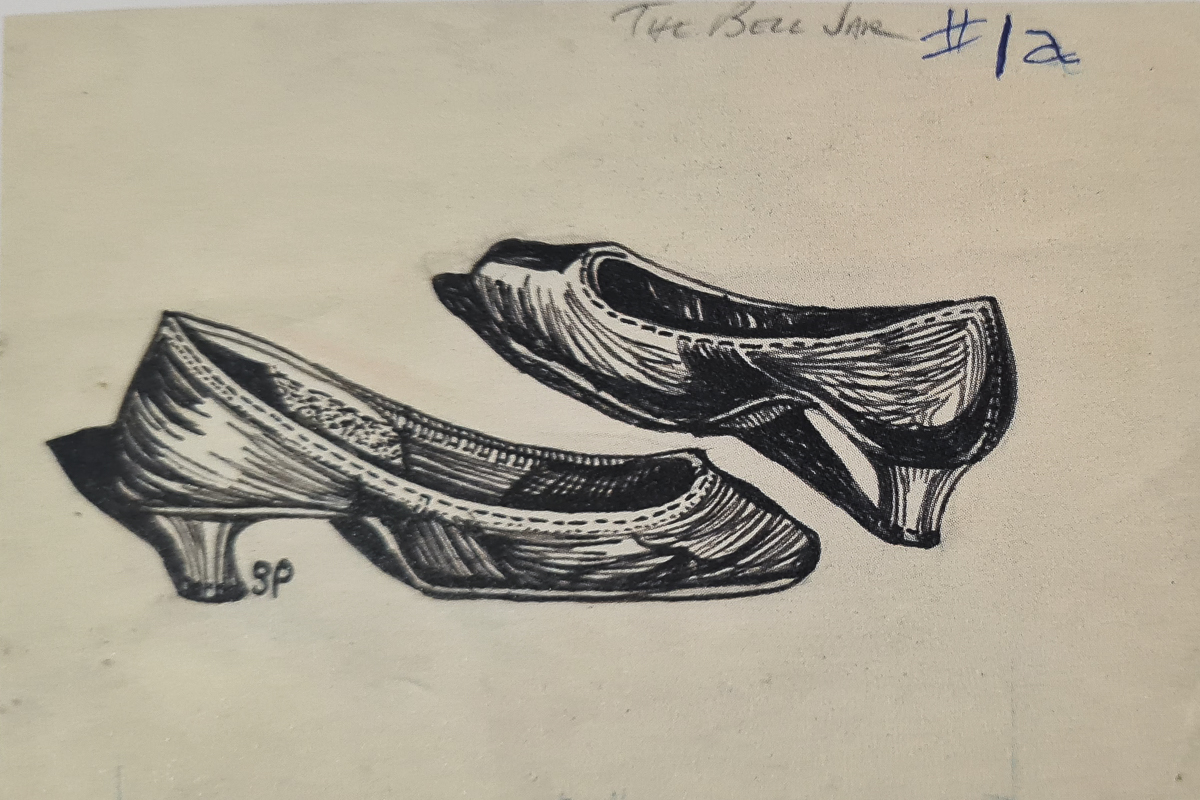

In a later letter to Ted, Sylvia describes her developing style as a “child-like simplifying of each object into design, peasantish decorative motifs.” Even so, some of her sketches are haunting. A 1956 study of shoes is labelled with The Bell Jar, suggesting that it was intended for the novel that was eventually published in 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas, just weeks before her suicide.

Copyright: The Estate of Sylvia Plath

Many of her drawings are incomplete. Some are just lines, scaffolding for the actual art that never came, while some others are half-pictures, with details missing in parts. A jigsaw puzzle with pieces lost to time. Although she might have left those manors and meadows for good, not intending to return to finish the drawings, the art has the same eerie effect on you as her poetry collection, Ariel: The Restored Edition, which featured poems in Sylvia’s original arrangement, unchanged by Ted Hughes. Both works hold the makings of a masterpiece halted abruptly by the cold hand of untimely death.

Copyright: The Estate of Sylvia Plath

The drawings are not just therapeutic for Sylvia, but they also feed her writing. In a journal entry dated August 21, 1957, she describes the rough outline and character sketches for a story centred on two antique corn vases. This book reproduces her sketch of a particularly ornate corn vase from the same year. Did the drawing birth the story? Or did her unflinching focus on the story make her draw the vase? We might never know. But to see both the art forms collide in a rare book that offers a glimpse into the mind of one of the greatest poets of the 20th century is priceless.

Get this singular book of Sylvia Plath’s drawings, and find other hidden gems, by walking into a Kunzum bookstore near you.

Related: A Room of One’s Own: What Virginia Woolf’s Inquest Tells Us about Women’s Spaces

2 thoughts on “Sylvia Plath’s Drawings: The Lesser-Known Art of a Famous Writer”