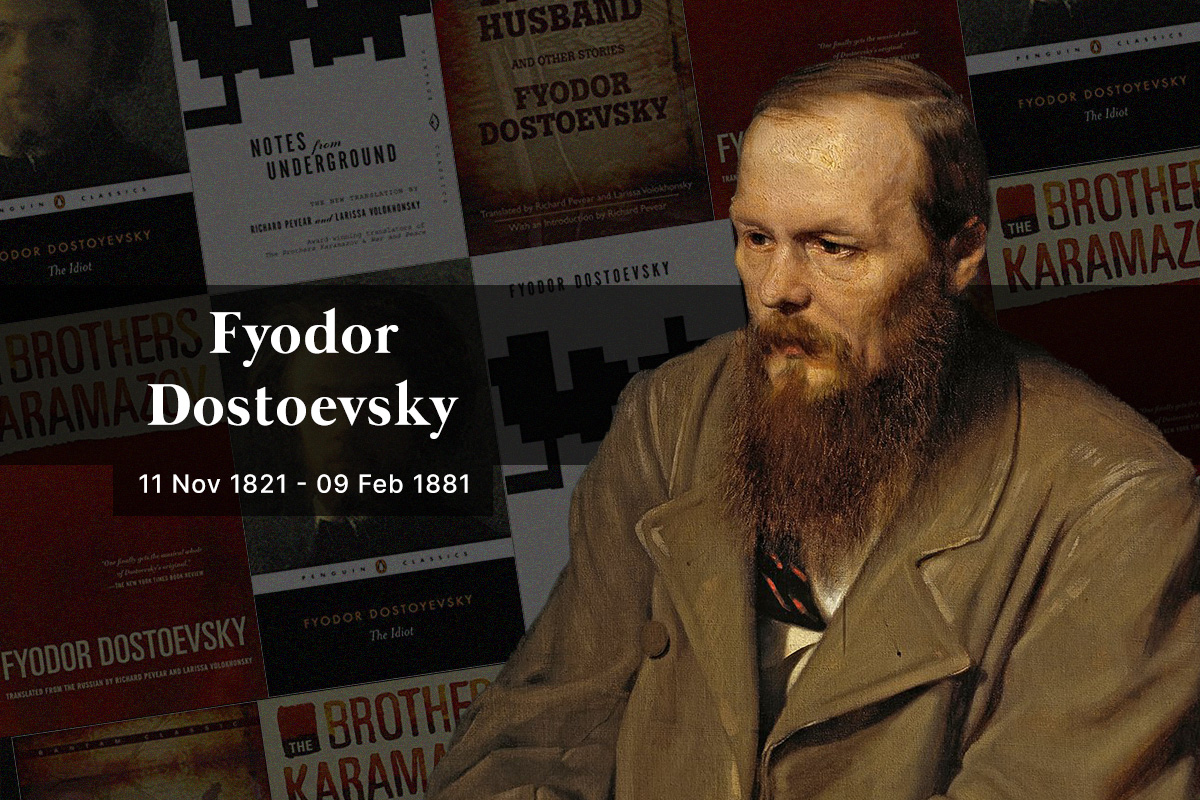

The Russian writer behind seminal works like Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and Notes from the Underground, dipped into his own trials and humiliations to craft his dark stories and complex characters. On his 201st birth anniversary, Kunzum revisits his life struggles and literary brilliance. By Sahil Sihag & Sumeet Keswani

Fyodor Dostoevsky is regarded as one of the greatest writers to have ever lived. Literary modernism and various schools of psychology and theology have been deeply influenced by his ideas. His most important works were once featured as chapters in issues of Russian Journals, reading which made for the high point of the day for many people. His four lengthy novels were all about putting the norms of his time to the test: Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880) capture the Dostoevskian stream of consciousness. They now populate the ‘Classics’ bookshelf of most bookstores, including Kunzum.

If you’re new to reading Dostoevsky, his twisted characters may take you by surprise. For this reason, you ought to know of the close connections between his life and literature. Born on November 11, 1821, the Russian was destined to experience hardships that outweigh even those inflicted on his fictional characters. For starters, he didn’t enjoy the familial money and privilege that most of the other Russian authors of the time did. It’s hardly a surprise that his first novella, the epistolary Poor Folk, focused on the humiliations suffered by an impoverished copying clerk. It found Dostoevsky fame, but he was soon cast side by the critics and writers of the time due to his behavioural quirks. We now know that Dostoevsky suffered from depression.

But the writer was never one to be tamed by criticism or boycott. He revelled in his individualism. Few things can give readers a truer glimpse of his mind than this letter he wrote to a friend:

“I want to do an unprecedented and eccentric thing, to write thirty printed sheets (480 Printed Pages) within the space of four months, forming two separate novels, of which I will write one in the morning and the other in the evening, and to finish them by a fixed deadline. Such eccentric and extraordinary things utterly delight me. I simply don’t fit into the category of staid and conventional people…”

Dostoevsky’s protagonists are always well-read individuals who have been overlooked by the social attitudes of their time. They reflect the kind of life the author led himself. Dostoevsky was arrested in 1849 for being part of a secret revolutionary group that opposed serfdom. He spent eight months in prison before suddenly being condemned to execution at a public square. The execution was halted at the last possible moment, with a letter of mercy by the Tsar, which drove one of the prisoners insane. The death sentence was replaced by four years of imprisonment in a Siberian labour camp, followed by an indefinite military service. But nothing came in the way of Dostoevsky’s writing; all of his trials, tribulations, and humiliations fed into his work.

The mock execution may have been a severe punishment in itself but it led Dostoevsky to write convincingly and memorably about the mental state of a person on death row: Prince Myshkin of The Idiot. This character also suffers from epilepsy, and Dostoevsky’s visceral narration of his seizures echo his own attacks, which started in prison. His experiences in the Siberian camp inspired The House of the Dead, and started a new literary movement in Russia. Not only did the work shed light on the cruelty of his captors and the evil that makes humans beings commit gruesome crimes, but it also emphasised the importance of individual freedom — in stark contrast to the prevailing ideologies of determinism and socialism. Notes from the Underground took this criticism of contemporary ideas a step further with an unnamed narrator launching into a direct attack.

Dostoevsky is known to play mind games with his readers by drawing them into the psyche of humans who commit crimes that they justify with peculiar reasoning. His characters are like pieces in complicated chess problems who remain the same to their bitter end, replete with their eccentric features and habits. A prime example would be Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. He murders a pawnbroker, convinced that it’s an act with a higher purpose of helping others, and hence, isn’t a crime at all. Much like the detective Porfiry Petrovich, who works on Raskolnikov’s emotions to get him to confess, Dostoevsky draws out the darkest thoughts and dilemmas out of the minds of his reader. The protagonist’s disavowal of morality is completely contradictory to the author’s own ideology, but he was never written as a vessel for Dostoevsky’s thoughts; instead, he represents the radical thinking of the intelligentsia of the time who stood staunchly opposed to Dostoevsky’s advocacy for every person’s freedom of choice.

Dostoevsky’s love life wasn’t without troubles either. His first marriage in 1857 was an unhappy one to a former widow who lived for just seven years after the union. His romantic dalliance with another author, Appolinariya Suslova, in Europe inspired parts of the 1866 novel The Gambler, which also reflected the writer’s own addiction to gambling. In 1867, he married the stenographer who helped him finish the novel in the nick of time (he was on a deadline imposed by the publisher). This marriage was relatively successful and the couple had four kids, but just two of them made it past childhood.

As a reader, I sympathise with Dostoevsky’s many misfortunes but I also know they were integral to his terrifying stories and psychological portraits. His work, notwithstanding its inspirations, forever changed the literary landscape and remains relevant even today, over two centuries later. And he lives on through it.

Today marks the 201st birth anniversary of Fyodor Dostoevsky and hence makes for a great day to revisit his epic works—or pick up one that you haven’t yet read. Kunzum stocks the Russian’s best-known tales as well as lesser-known writings.

Related: Sylvia Plath’s Drawings: The Lesser-Known Art of a Famous Writer