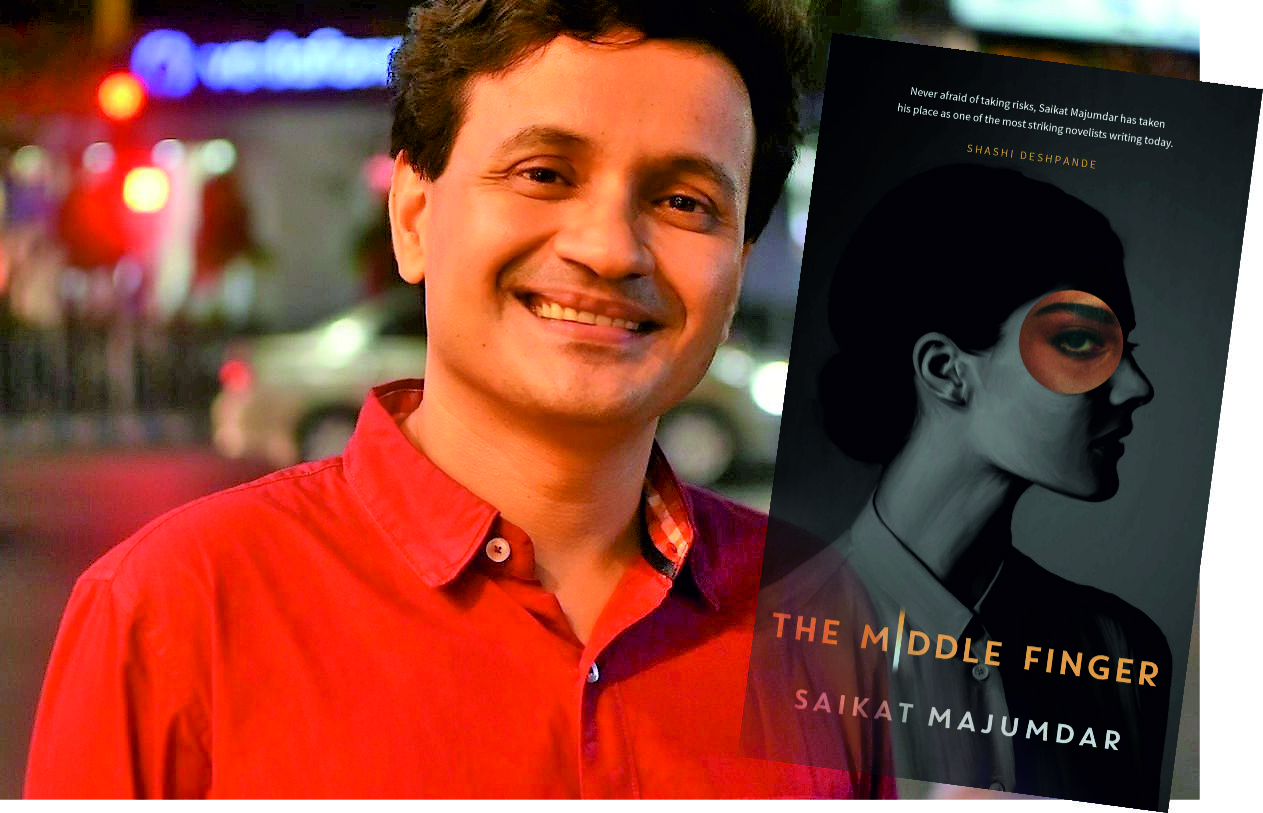

Where would we all return if not to love? Why won’t we die, to live? Saikat Majumdar’s latest novel is about love, and sacrifice. It’s about Eklavya giving up his thumb to his guru. It’s about Megha returning to arrange a bookshelf with Poonam.

In a world in transit, The Middle Finger travels through its strictly sheltered alleys and leaves behind a sparkling smudge. “…this novel reveals an intersection of many kinds of identity, particularly marginal identities. Queerness in liberal and progressive atmospheres can be open and can name itself,” says Saikat in conversation with Shruti Kohli, Managing Editor, Kunzum.

Shruti: The first thing that stood out in your book is the shortness of the chapters. Was there a particular reason to do so – considering people’s attention span – or is it just how it happened as you wrote the story?

Saikat: I think I’m a writer of “short fiction”, even when I write novels. I’m more interested in small and ordinary stories, fragments of our immediate reality, than in the grand, the epic, and the fantastic. My novels are usually slim and depict the lives of a few people caught up in some locally grounded events. Also, I imagine fiction more as physical scenes rather than narrated sequences, which is why, I guess, my writing has been described by some critics as “cinematic”. If I can create a powerful scene that says something about the characters and their relationship, that, for me, is good enough for a chapter. A scene that feels natural, even raw and smarting, sometimes even a little unfinished, as in real life. When I tell a story, I don’t feel obligated to explain, analyse or offer a lot of information.

Shruti: How did you research for your book?

Saikat: Researching to write fiction, for me, is trying to relive intense memories. There are no facts to research – those are either fabricated, or when they are true, come from accessible memory. It’s the feelings that need researching. I try to re-inhabit moments and people that have provided inspiration for the characters, even when it’s just small, partial inspiration. Or try to be other people, to imagine how one must feel. The nature of feeling, emotion, and atmosphere is more important in fiction than factual details. Writing a novel as this one, with the lives of people very different from my own, required me to become many different people, people very different from who I am.

When I come across a powerful visual or impression, either directly or through someone’s narration, it stays with me and some of it resurfaces in my fiction.

Shruti: Fiction is not really all fiction. The house in the Kolkata slum, the acid mark on the floor, the shrieks of chickens, old primary school accommodation with high ceilings in the US…Did you happen to see or experience all of this at some point in life? Or did you hear about some of this? How did it all come together in your story?

Saikat: Thank you for noticing these important details. Such details are very important for me as a fiction writer. They all come from real life. Some of these I’ve seen myself, and others I’ve heard people talk about in a vivid and unforgettable way. Like the housing colony in the middle of a market, above a butcher’s shop – I know a vegetarian person who had to live there. When I come across a powerful visual or impression, either directly or through someone’s narration, it stays with me and some of it resurfaces in my fiction. Some of it claims a subterranean importance in the story – such as this story of meat, vegetarianism, and butchery.

Shruti: Until only two years ago, same sex relationship was strict taboo even in parallel cinema and literature. In fact, it was frivolously used as a mock in mainstream movies and literature. Now, it’s everywhere, almost every movie and TV series made in the past two years, has a strong queer presence. How do we explain the shift and how has it impacted reading?

Saikat: I think there are different ways to look at this shift. One is that same-sex relationships are now widely accepted. Sometimes they reveal elements of transgression in the most ordinary stories. I know I’m drawn to emotions and relationships that break rules – most of the time they remain unrealized but their very existence is a kind of a threat. Readers of novels have long been used to transgressions – think of adultery and the 19th century novel, for instance. The important thing is to keep the transgressive instinct alive without falling prey to the fashion of what is ‘hot’ or ‘in’. The relation between such artistic transgression and political activism, however, is never easy to formulate.

Only through reading can you establish a fluid relation with language that can give you a certain meaning and command of your life.

Shruti: How difficult or easy was it for you to portray not just queer relationships but queer relationships in two very different environments? Each of the two couples are based in contrasting environments – Alberto and Kevin are in a comparatively more progressive place while Megha and Poonam’s love takes seed in a less progressive environment and they end up in not just a regressive but a hostile place.

Saikat: That’s a great question! You’re absolutely right – this novel reveals the intersection of many kinds of identities, particularly marginal identities. Queerness in liberal and progressive atmospheres can be open and can name itself. In less enlightened atmospheres, dissident sexualities do not even get a name, much less support or approval. But sometimes relationships that grow between unlikely people, separated by large social and cultural differences, are harder to perceive. Sometimes acknowledging something, giving it a name, causes it to exist. Without that name, it is just a wild force, an intangible emotion.

Shruti: Did you have two, or three, different endings in mind before you settled for this one? Would you call this a happy ending?

Saikat: To an extent, the ending was claimed by a certain re-imagination of myth. I wanted to write a story where Drona turns away from Arjun and supports Ekalavya. But that has to come at the end of a transformative, even difficult experience for Drona. I was also drawn to the idea of learning as a giving experience, as a means of profound connection between two people. I would call it a happy ending. But a happiness that is hard to name, that perhaps cannot be named.

Shruti: How did publishing your first book change your process and style of writing?

Saikat: My very first book was a collection of short stories published by P. Lal from Writers’ Workshop when I was in college. I think that event inspired me to become a writer, whatever of that ambition I understood at that time. My first novel was published years later, shortly after I finished my Ph.D. Ironically, I think the latter was written in a more simple and direct style. I think growing as a writer usually means writing in a style that comes from somewhere deep inside you, and speaking in a voice that is true to the experience and emotions described, rather than assuming a uniform writerly cleverness all the time, which seems attractive when one is younger.

Queerness in liberal and progressive atmospheres can be open and can name itself. In less enlightened atmospheres, dissident sexualities do not even get a name.

Shruti: What’s your message, as an author, for young readers?

Saikat: First, read anything you want. In the beginning, forming a habit to read is more important than being selective about what you read. Once you feel reading is a steady part of your life, try to reach beyond your comfort zone, beyond books and subjects that naturally draw you. Literature is our great opportunity to experience otherness along with odd and intense versions of one’s self. Once you are more confident as a reader, push yourself to reading different things. Only through reading can you establish a fluid relation with language that can give you a certain meaning and command of your life, both personal and professional. Nothing else can give you that. Reading also distils a form of concentration that can be adapted to many other tasks and goals. It is meditation with some fun thrown in!

Loved reading about how the author carves out characters and relives intense memories before writing about them.

This line is absolutely true! “Only through reading can you establish a fluid relation with language that can give you a certain meaning and command of your life, both personal and professional. Nothing else can give you that.”