Murakami’s men are not so much alone as they are solitary individuals without an emotional centre, without any firm emotional connections that tether them to their world, Drishya Maity writes

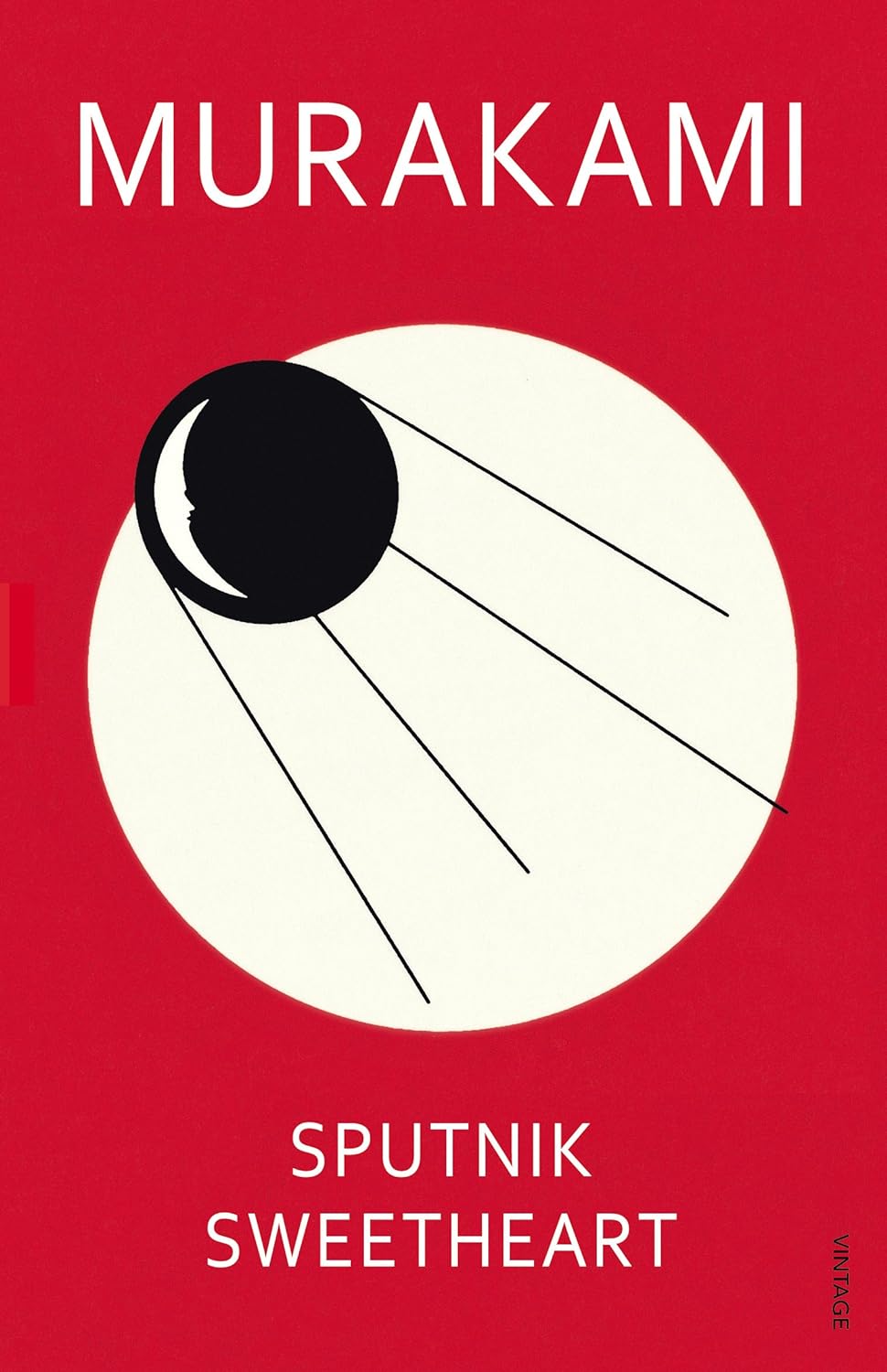

“Why do people have to be this lonely? What’s the point of it all? Millions of people in this world, all of them yearning, looking to others to satisfy them, yet isolating themselves. Why? Was the earth put here just to nourish human loneliness?”

K—the narrator-protagonist of Japanese author Haruki Murakami’s novel Sputnik Sweetheart (2001)—wonders while lying alone on a slab of stone on an unspecified Greek island, gazing at the sky, looking for the light of a satellite (in Murakami’s words: “Lonely metal souls in the unimpeded darkness of space, they meet, pass each other, and part, never to meet again.”) Only — he is not alone in feeling this lingering sense of loneliness. This is a recurring theme in Murakami’s decades-spanning body of work — a theme he keeps returning to and examining through different characters: most of them men, all of them predisposed to floating through surreal, slightly-shifted alternate realities with the same lingering sense of loneliness, isolation, and alienation.

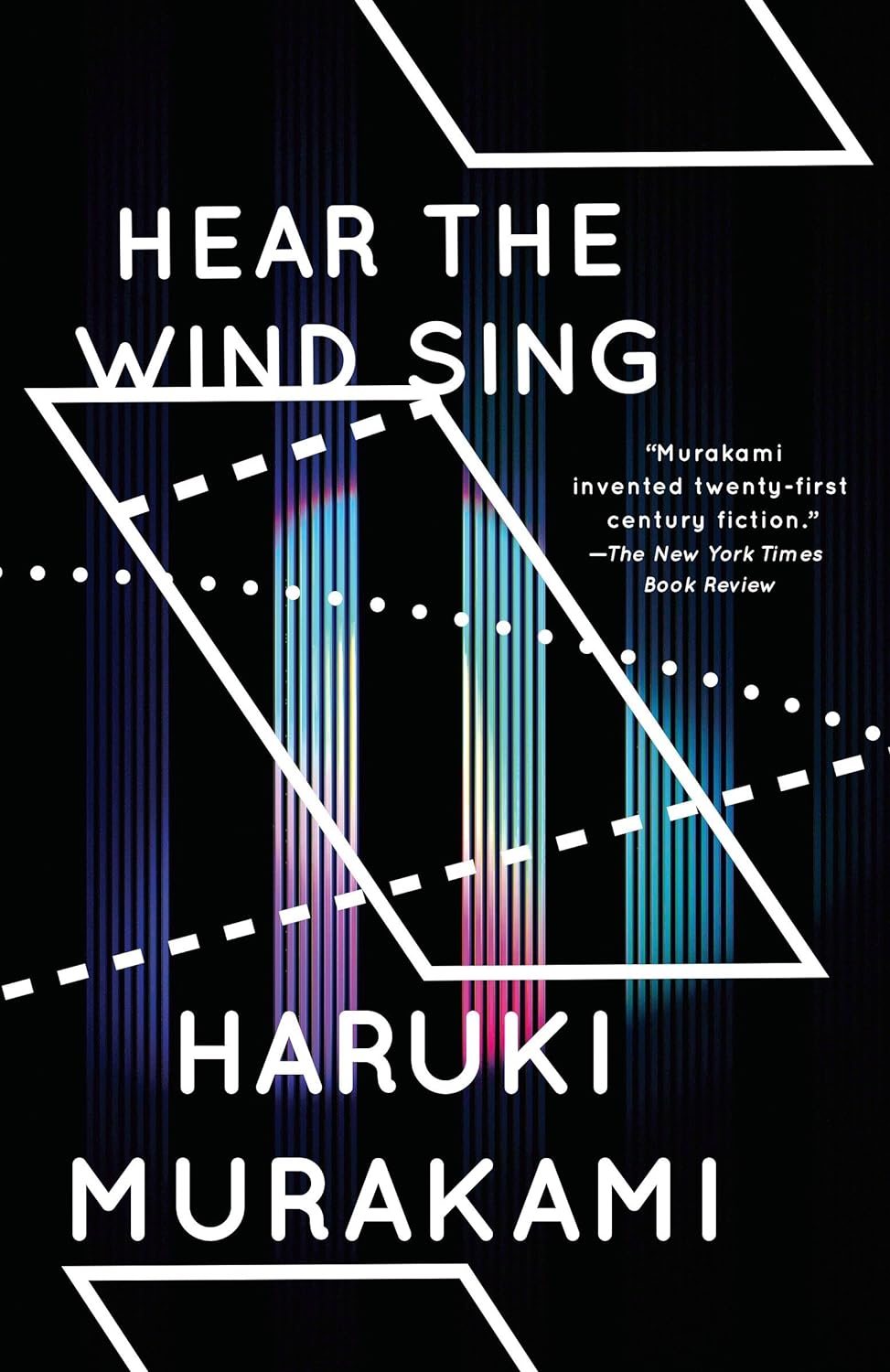

The beginnings of this exploration of male loneliness in Murakami’s works can be traced back to his very first novel Hear the Wind Sing (1987) and its sequel Pinball, 1973 (1985)—later published in English as a single volume under the title Wind/Pinball (2015)—in which the nameless narrator-protagonist reminisces about the summer of 1970 when he returned to his seaside hometown in Kobe from his university in Tokyo during the summer holidays; his friend “the Rat;” his brief relationships with his college girlfriend who died by suicide, a nine-fingered girl he found unconscious in the washroom of J’s Bar that summer, and a pair of unnamed identical twins who mysteriously appeared in his apartment in Tokyo one morning in the spring of 1972; his mid-twenties as a freelance translator; and his memories of the 1968-1969 Japanese university protests.

Much like many of Murakami’s later works of fiction, the narrator of these early short novels, too, is a detached, emotionally distant character whose deadpan demeanour and dry humour stands in stark contrast with the other characters that inhabit their world. In this way, the unnamed narrator-protagonist of Wind/Pinball turns out to be the precursor to Murakami’s men — estranged, alienated, transparent non-entities whose primary narrative purpose is to serve as lenses that focus on and magnify the peculiarities that surround them. This is something Murakami returns to time after time in his work:

In Killing Commendatore (2018), the narrator-protagonist—another unnamed man—is abandoned by his wife and finds himself holed up at a famous artist’s home in the mountains. When he discovers a strange painting in the attic, he opens a circle of mysterious circumstances. To close it, he must complete a journey to a metaphorical underworld.

In Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and his Years of Pilgrimage (2014), the protagonist Tsukuru Tazaki is abandoned by his four best friends from school. One day they call him and announce that they do not wish to see him or talk to him ever again. Since then he floats through life, unable to form intimate connections with anyone.

In South of the Border, West of the Sun (1999), the protagonist Hajime is an only child—a term he detests—from the first generation of Japanese children born after WWII when having two or three children in the family was considered typical, and it was accepted that only children were spoiled, weak, and self-centred. As such, Hajime has an inferiority complex about it, and he grows up friendless and aloof. His later life is dominated by these melancholy feelings of solitude and isolation even when he is married with children.

What explains Murakami’s near-obsessive fascination with male loneliness? Is it his own feelings of isolation and alienation and unhappiness in the literary world in Japan? Is it because, in his own words, he is considered kind of an outsider — a black sheep, an intruder in the world of mainstream, traditional Japanese literature?

Like the best of Murakami’s distinctive, beguiling novels and short stories, the answer is always in the oblique, never in the obvious. The truth is Murakami’s men are not so much alone as they are solitary individuals without an emotional centre, without any firm emotional connections that tether them to their world and, more often, themselves. In fact, they are almost always surrounded by other people — friends, lovers, wives, co-workers, and strange acquaintances. Their sense of loneliness, isolation, and alienation, then, is almost always entirely internal — it comes from deep-rooted feelings of psychological isolation, from their own, personal experiences of unresolved loss and unmet need for intimate connections.

This is perhaps more apparent in Murakami’s elusive short fiction, especially in the collections Blind Willow, Sleeping Women (2006) and The Elephant Vanishes (1993). In almost all of the short stories in these two collections simple, straight-forward, mundane everyday situations—a routine visit to the hospital, a chance encounter, an extramarital affair with an older, married woman, a job interview, a phone call—are altered by how Murakami’s male protagonists, who sometimes also happen to be the narrators of their own stories, react to them in classic Murakami fashion with claustrophobic poignancy and wistfulness laced with idiosyncratic humour. And this rises to a crescendo in Men without Women (2017).

In ‘Scheherazade’—one of the stronger stories in Men without Women—a man who is home-bound because of an unspecified reason (Is it punitive? Is it because of an illness? Is it self-imposed? We never know!) is visited twice a week by a woman who provides him with groceries, sex, and strange and gripping stories. The man does not have much else to do, no one else to talk to, no one to phone, no computer to access the internet, and he never watches television. Should the woman’s visits cease for some reason, the narrator tells us, the man would be left all alone, and all his ties to the outside world would be severed. But he is not overly concerned about this possibility. If that happens, he thinks, it will be hard, but I’ll scrape by. I’m not stranded on a desert island. No, the man thinks, I am a desert island.

There is a kind of Zen acceptance in how Murakami’s men approach their loneliness. They play the role of passive spectators, isolate themselves inside metaphorical caves, and accept their self-imposed psychological exile with the warmth of memory. Murakami paints his characters’ deep sense of loss and loneliness with an undertone of calm acceptance of their vanishing vitality. Near the end of the story, the protagonist of ‘Yesterday’—another story from the collection titled after The Beatles’ song—reflects:

“…when I look back at myself at age twenty, what I remember most is being alone and lonely. I had no girlfriend to warm my body or my soul, no friends I could open up to. (…) For the most part, I remained hidden away, deep within myself. Sometimes I’d go a week without talking to anybody. That kind of life continued for a year. A long, long year (…) At the time I felt as if every night I, too, were gazing out a porthole at a moon made of ice. A transparent, eight-inch-thick, frozen moon. But no one was beside me. I watched that moon alone, unable to share its cold beauty with anyone.”

And, again, in the eponymous Men without Women, the narrator-protagonist—after learning about the passing of a former lover—thinks:

“Suddenly one day you become Men without Women. That day comes to you completely out of the blue, without the faintest of warnings or hints beforehand. No premonitions or foreboding, no knocks or clearing of throats. Turn a corner and you know you’re already there. But by then there’s no going back. Once you round that bend, that is the only world you can possibly inhabit. In that world you are called “Men without Women”.”

In this way, in trying to reach out and find each other, and in failing to do so, Murakami’s men become islands unto themselves until one day they come up against the shadow of their own solitude and embrace it with a sense of wistful nostalgia for all that is already lost and all that eventually will be. They become men without… men without women, men without the world, men without themselves.

Pick these books from any Kunzum store or WhatsApp +91.8800200280 to order. Buy the book(s) and the coffee’s on us.