Mmhonlümo Kikon, author of His Majesty’s Headhunters, a seminal work on the Battle of Kohima and the role of the Naga Headhunters of Nagaland says his book is a necessary contribution to discourse on the idea of India.

Bhavneet: Your book, His Majesty’s Headhunters, is something which would have taken you a lot of time, patience and a lot of research. How did you go around working on that research?

Mmhonlümo Kikon: I had a fair idea because in the kitchens, in any social gatherings we would discuss the Battle of Kohima. Priority has also been given to it by even the state government because we have the World War 2 cemetery in Kohima and also a World War 2 museum in Kisama, the site of the Hornbill Festival. There was a lot of discussion happening everywhere. It prepared me mentally and I had a very clear idea of what I wanted to know and what I wanted to write. The only issue was getting the Japanese side of this story because it was written in Japanese and not readily available in India. I had to go through a lot of books which were written by both the Britishers, Americans and some Japanese writers. I went to museums, to libraries, and I have my own collection of books. But having said that, the background of it, especially the colonial history of the Naga Hills in the 19th century, was readily available. It took me two years actually to finish the research and after that it didn’t take me much longer. I wrote and edited it several times for around six months.

BSA: The Northeast was always a pain point for the Britishers. They never actually could control the entire region properly. What kind of revelations did you come across during the research for this book?

MK: It was very convenient for the British to demarcate what areas they can control, what they couldn’t or didn’t want to control in terms of the fact that the resource and revenue interest was not there in the hills, especially in Naga hills, Miso Hills, Lushai hills, and generally the borderline between present day Myanmar and India. So they focused on the plains in Assam due to their tea plantations and the oil exploration plus the elephant trade that they practiced mostly was focused in areas in Assam, which were bordering both the Naga Hills, Lushai Hills and even present day Arunachal. It was difficult for them to control the Northeast because they didn’t have the economic interest and their policy was driven essentially by revenue and resource.

BSA: The Naga hills have always been a very interesting area. It’s a very unexplored area. It has its own culture. The way life is lived there is very different from the rest of the country. In all of that, how did you decide to pick up a topic like this one?

MK: For many years, anthropologists have shown interest in the area and also because of the conflicts that exist there. Political scientists and journalists also wanted to write, and they have been writing about both the conflicts and also the demographic side of the Naga people. However, because of the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Kohima, there has been a recent surge of interest in the topic both among the Japanese and the British and American societies and that interest led to a lot of sporadic research being done and books being written but there has never been a narrative from the Naga side. They would always want to separate the Battle of Kohima, that period of three months in 1944 from the colonial history, which is like 100 plus years because the Britishers first came to the Naga Hills in 1832 and it took them 45 years of conflict and violence and war. Usually in India you hear a lot about the Battle of Plassey, the Revolt of 1857, but you wouldn’t know about regions where the Britishers were resisted and challenged by various communities in India. So here is one such story which has not been told.

BSA: Do you think that this story has the potential to bring the northeast closer to the rest of the country?

MK: Definitely. If you want to continue with the discussion 75 years after India’s Independence on the idea of India, then this book is a necessary contribution to that discourse on the idea of India. It completes the entire discourse on the idea of India.

BSA: It’s been so many years now that the battle of Kohima took place. It must have trickled into the folklore and folk history of the Northeast. Are there variations of the same battle happening within these those stories?

MK: There are variations because there are new narratives being told. The only issue is it’s not being written. The only issue is that the Japanese are now coming. I’ll give you a very recent example: see the British, in spite of the fact that the Nagas supported the British, as much as you know, the Indian National Congress led by Gandhi at that point of time before Independence, supported the British. However, post-Independence, they (the British) were very grateful for the help rendered by the Nagas as intelligence gatherers, as porters, as stretcher bearers, but they have not really done anything for this region. I’m not saying that we want something from them, but when the Japanese came, they came with projects to uplift the region. They’ve been supporting the state governments with various projects, especially for the rural sector.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is present in all the northeastern state with funding. Unlike the British who have a war memorial in terms of a war cemetery, the Japanese, after losing the Battle of Kohima in the Second World War, have started making peace parks, and they’re doing it on their own. There’s one being built even now because it’s going to be 80 years next year of the Battle of Kohima and they want to commemorate that with this park.

BSA: Do you see these parks as sort of a repentance for what happened during that time, or maybe coming to terms with what happened at that time?

MK: If you remember, before Abe died, he had pushed for the interest of the descendants of those Japanese Imperial Army men. A lot of them (the descendants) could not retrieve their dead bodies in Indo-China, Indonesia, Malaysia and parts of Nagaland. So they instituted a commission to go and search for the bones of the dead Japanese soldiers. And that is a government program of Japan.

It’s interesting because they also have this philosophy that if you don’t bury their dead properly, given them the proper burial, then their soul will not find peace.

BSA: Has there been any success? Have they managed to find any remains?

MK: They’ve managed to find some. They have come to Nagaland, they’re still digging for the bones. And I’ve written about this here as well connecting it with the similar animistic belief of the Nagas with the Japanese belief. A lot of discussions are now emerging out of the interactions that we’re having with the Japanese government and the people.

BSA: When the Second World War started and the Japanese started invading, a lot of Indians had to flee from Burma and come in to India. Is there any mention of that?

MK: Definitely, because the entire organization of the Naga Labour Corps could be perfected because they had experience of handling the Indians who were coming from Myanmar via the Naga Hills, because that’s the only route towards Dimapur because Dimapur was the nearest railway station from which they could travel to the rest of India. There is a place in Dimapur called Burma Camp, even now. This actual place was the actual place where all the refugees came and stayed. And a lot of people died. But the Naga people were able to tend to the sickly. And there was another hospital there. This is pre-Independence time, this is pre-1944, around 1941-42.

Around that time there was a British Deputy Commissioner, Charles Pawsey, who – interestingly for me as a literature student – was a classmate of Graham Greene, he was an ex-army man and was able to use that experience of handling the refugees from Myanmar because that time it was called Burma and the Japanese has already captured Burma. So the fear was that the British would have to prepare for the war against Burma from 1941 onwards. It was as early as that. But they could not have levelled up their capacity and also the ability to resist and repulse the Japanese Imperial Army if the Americans had not helped them. So the American military engineering engineers came and actually improved the railway network there in the Northeast especially the whole of Assam.

There was a lot of history going on and that time, the only success of the Allied Forces because it was already the Second World War, was in Arakan by the Chindits, the famous word was coined after that, and then because of the victory there, with the aid of the American airplanes, they were able to secure that. Today that history is being revisited. This is one book where it attempts to revisit the entire period, but also connects it to the present-day political situation of the region. The geopolitics of that battle has always been neglected. It’s not being given its due importance. Today a lot of conflicts are just spill overs of the colonial period. And if you understand the past, you will be able to facilitate proper resolution of all the conflicts in the region.

BSA: You earlier spoke of how the Japanese were had already started translating your book. Would you please comment on that?

MK: There is a discussion going on of translating this book into the Japanese language. I have given due importance to General Sato’s activities. As a general he was different from the other Japanese generals. In that he chose to oppose or rebel against the plan because he realized that there weren’t enough resources to maintain the assault on Kohima and without enough resources, they would not be able to sustain. He was also the first one to say that we should withdraw. The concept of surrender, I think did not really exist with the Japanese Imperial Army. It’s like the Nagas; the Naga head hunters do not have the concept of surrender. We don’t understand surrender. It’s either defeat or victory. So our headhunters and the head hunting practice was based on a certain philosophy and concept which people, because today we are no longer headhunters, don’t understand their context. And also the parallel that we draw from the Japanese onslaught and also why they came and how they came and how they sustained and then why General Sato decided to withdraw. Among all the generals who were involved in that theater of war, General Sato’s role was most important. I would want to do more research on General Sato, but because of the ambit and the scope of this book, I limited it to two or three chapters. I find him very very interesting, because at the end of the day, he was the central figure who was responsible for doing something which the Japanese army would consider unthinkable: A withdrawal.

BSA: That was not there in their entire concept of war.

MK: It’s not in their concept. And his superiors, especially Mutaguchi, who was another strong-headed general. He wanted to go ahead with the assault, continue their assault in spite of the fact that he knew that they were losing.

BSA: Now that this book is done, it’s already out. What next after this? Is there going to be a sequel to this?

MK: There’s a lot of demand, in fact, by historians who have communicated with me after reading the book that I think this book deserves a sequel. So I’ll be giving a thought to it, but definitely I’ll be writing more.

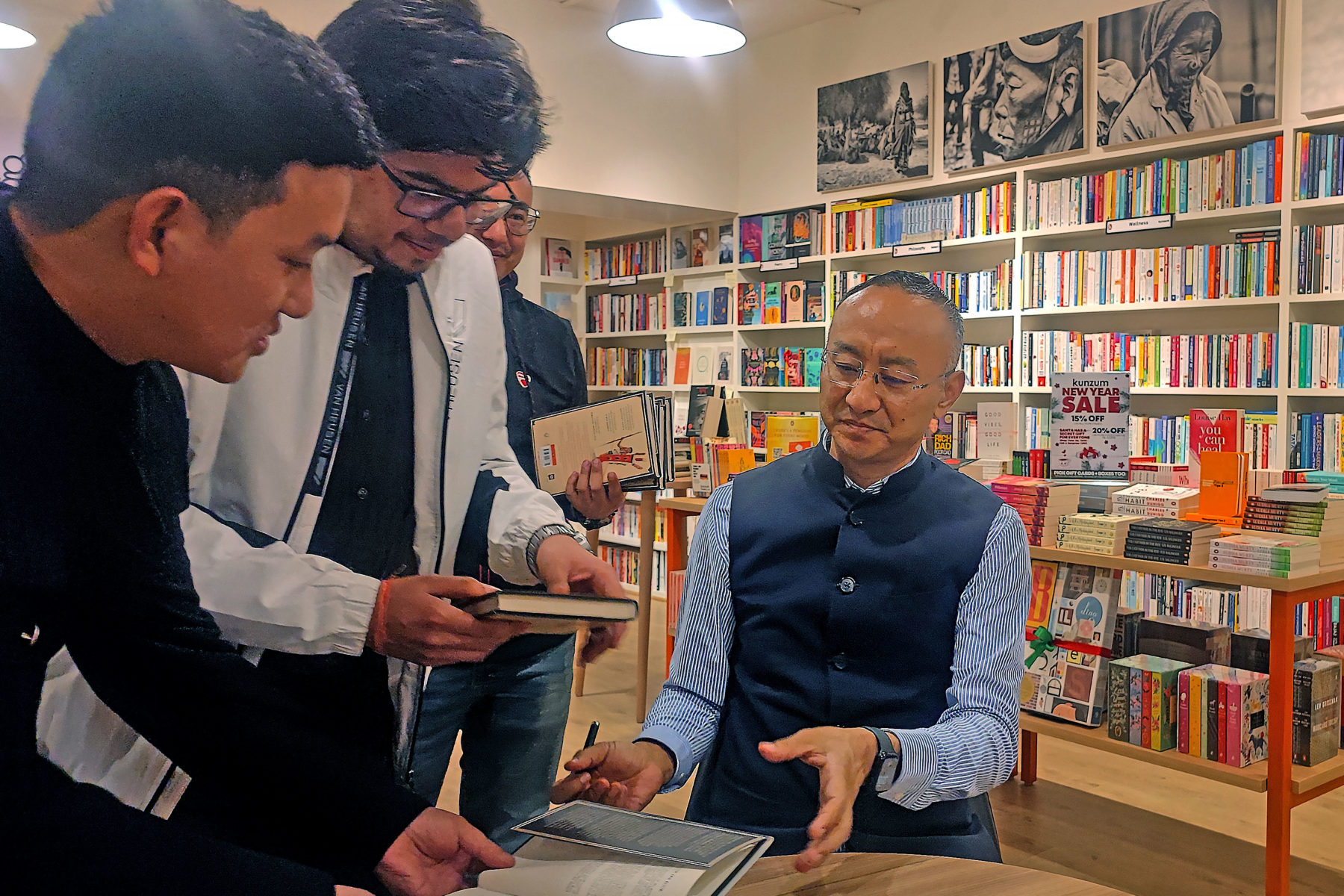

Pick up Mmhonlümo Kikon’s His Majesty’s Headhunters from any Kunzum store or WhatsApp +91.8800200280 to order. Buy the book(s) and the coffee’s on us.