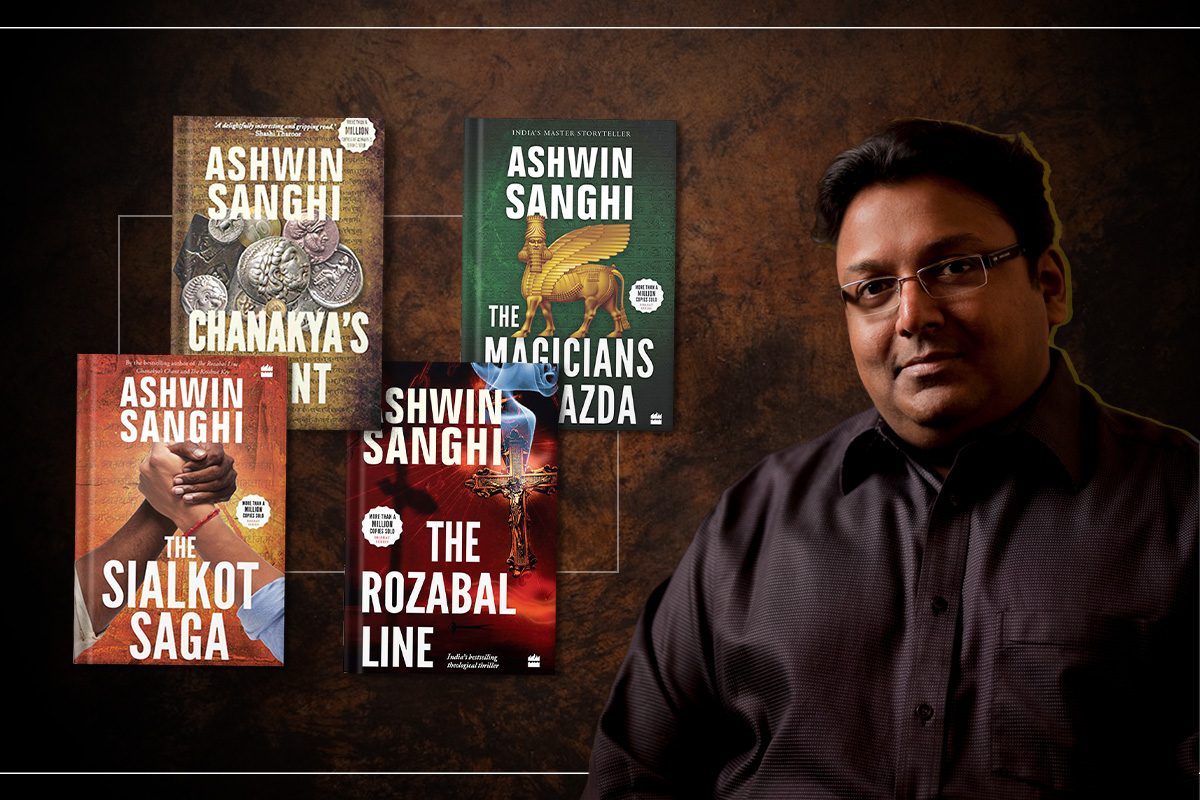

Ashwin Sanghi has crafted a niche for himself with his peculiar combination of mythology, theology, and thrilling plots. This came out of a mixed inheritance of reading habits, he reveals to Kunzum in a candid conversation. By Sumeet Keswani

The author of seven books that make up the bestselling Bharat series, Ashwin Sanghi recently came down to the sunlit bookstore of Kunzum Vasant Vihar. He spent two hours chatting candidly with his fans, signing book copies, and sharing anecdotes from the making of his books. We sat down with him to understand how he crafts his unique books, the literary influences of his childhood, and what he wants to work on next.

A Conversation with Ashwin Sanghi

Kunzum: In your latest book, The Magicians of Mazda (Bharat Series #7), you have put the focus on the Parsi community. What made you do that and how did you go about the research?

Ashwin Sanghi: The Parsis are a minuscule community—their population in India is about 60,000, globally it is probably around one lakh. And yet, they have made massive contributions in terms of economics, politics, culture, and medicine. There isn’t a single sphere where they haven’t been incredibly influential. It was always on my mind that I would do a book based on this fantastic community, but the trigger was a flight I was taking from Delhi to Mumbai—seated next to me was Boman Irani. I told him that I’d like to do a story about the Zoroastrians who came to India, and he asked me to read the ancient Qissa-i-Sanjan. The next day, I was able to procure its English translation. It was tremendously fascinating, not only because it described the journey of the Zoroastrians from Hormuz to Diu and then to Sanjan [in Gujarat], but more importantly, it also tells you of the ancient connections between the Parsis and those who followed what we now call the Sanātana Dharma. For e.g., in Hinduism we have Asuras and Devas, and in Zoroastrianism you have Ahuras and Daevas; in Hinduism we worship and venerate the cow, but so do the Zoroastrians; deities like Varuna and Mitra are given a lot of respect in the Rig Veda as well as the Gathas; both use fire as a means to reach out to God—with yagya or yasna. So, I wondered whether that journey of the eighth century was one of fleeing Iran or was it, in some ways, a homecoming of sorts to their spiritual home.

Kunzum: Is there a religion or myth that you haven’t explored and would like to in a future book?

Ashwin Sanghi: Frankly, there are so many stories I want to write—a lifetime isn’t going to be enough. It takes me two years to write a book in the Bharat series, so I have to pick my stories carefully. The Rozabal Line touched upon the commonalities between Eastern spirituality and Christianity; The Krishna Key was fundamentally about the possible historicity of the Mahabharata; in Keepers of the Kalachakra, I have covered, to a great extent, the commonalities between the Shiv Shakti tradition and Tantrik Buddhism; in The Magicians of Mazda, Zoroastrianism has been covered. One faith I haven’t gone into great detail is Sikhism. More importantly, there are about 10-12 story ideas, because, as you know, not every book in the Bharat series is religion-oriented. Chanakya’s Chant is political, and The Sialkot Saga is business-oriented; there are many such spheres that I want to cover.

Kunzum: Which writers or books have influenced your storytelling craft?

Ashwin Sanghi: The greatest influence was that of my maternal granduncle, who lived in Kanpur. He would send me one book every week and expect me to read it and write a one-page letter to him, in which I’d tell him what I had read and whether I liked it or not—and my reasons for liking it or not. He got me into the habit of reading, and he would lovingly curate those books. There were classics, the Mahabharata retold by C Rajagopalachari, Autobiography of a Yogi (by Paramahansa Yogananda), Freedom at Midnight (by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre); there were also books that he wanted me to read but I couldn’t, like War and Peace (by Leo Tolstoy)—I couldn’t get through more than 25% and I still haven’t.

He rewired my brain because the stuff he sent me involved spirituality, history, philosophy, mythology—all the material that makes up the Bharat series. At the same time, my mother was also an avid reader, but a different kind. She was always reading the latest potboiler, from Jeffrey Archer to Sidney Sheldon, Arthur Hailey, Frederick Forsyth, and Robert Ludlum—and she would pass it on to me. So, for 15 years, I imbibed a lot of material from the stuff my grand-uncle sent me, but stylistically, I was loving the stuff my mum passed on to me. That’s why the Bharat series books are stylistically potboilers but the material they cover tends to be far deeper.

Kunzum: You’re often called ‘the Dan Brown of India’. Do you embrace that moniker, or would you rather not have that parallel be drawn?

Ashwin Sanghi: I’m probably Dan Brown’s greatest fan. So, any comparison to him is something I wear as a badge of honour. But the comparison is misplaced. The very first book I wrote was called The Rozabal Line—it revolved around the possibility that Jesus Christ could’ve been buried in Kashmir in a tomb known as Rozabal—and that story also had an element of the sacred feminine and some occult powers with Mary Magdalene. At that time [2007], any book coming out in that space was considered similar to The Da Vinci Code. So, it was easy to tag me as an ‘Indian Dan Brown’, but if you read The Da Vinci Code and The Rozabal Line, you realise they’re completely different animals. So, I think the comparison is misplaced—but do I have a problem with that comparison? Not at all!

Kunzum: If you had to recommend some books to our reading community—and be that granduncle figure for them—which would they be?

Ashwin Sanghi: The one book that has remained on my bedside is Autobiography of a Yogi. I must’ve read it at least 10-15 times over the years. There was a time when the stories being narrated to me felt like fantasy. It was this book that made me realise that just because I can’t explain something doesn’t mean it’s not real. So, I read it again and again, and every time I read it, I pick up something new from it.

The second book that influenced me a lot was Freedom at Midnight. That book made me realise that you can take a subject considered to be boring—in this case, history—and you can narrate it like a fascinating story. The realisation that history can be interesting came to me from there.

The third book that influenced me very much was Midnight’s Children. I realised it was possible to tell a story with an element of magic and still make it believable. Not just that, but also its language. If there’s one author I’m truly envious of, it is Salman Rushdie. I know I can never write like him. But I can aspire to.

The fourth book, hands down, is The Da Vinci Code. It’s difficult to come across thrillers that can take such archaic material and make it into a fast-paced thriller. It’s a study in page-turning, and I’ve always maintained that the greatest quality of a novelist is to make a reader turn the page.

The fifth author, not book, is Arthur Hailey. He would devote months to understand a setup, like hotels or the banking system, and then craft an incredible story around it. The reason that you see so much research in the Bharat series is because I’ve grown up on Arthur Hailey.

Related: Writing a Sequel to a Pulitzer Prize Winner: Less is Lost, But Andrew Sean Greer is Not

1 thought on “Talking Books with Ashwin Sanghi, the Man behind the Myths”