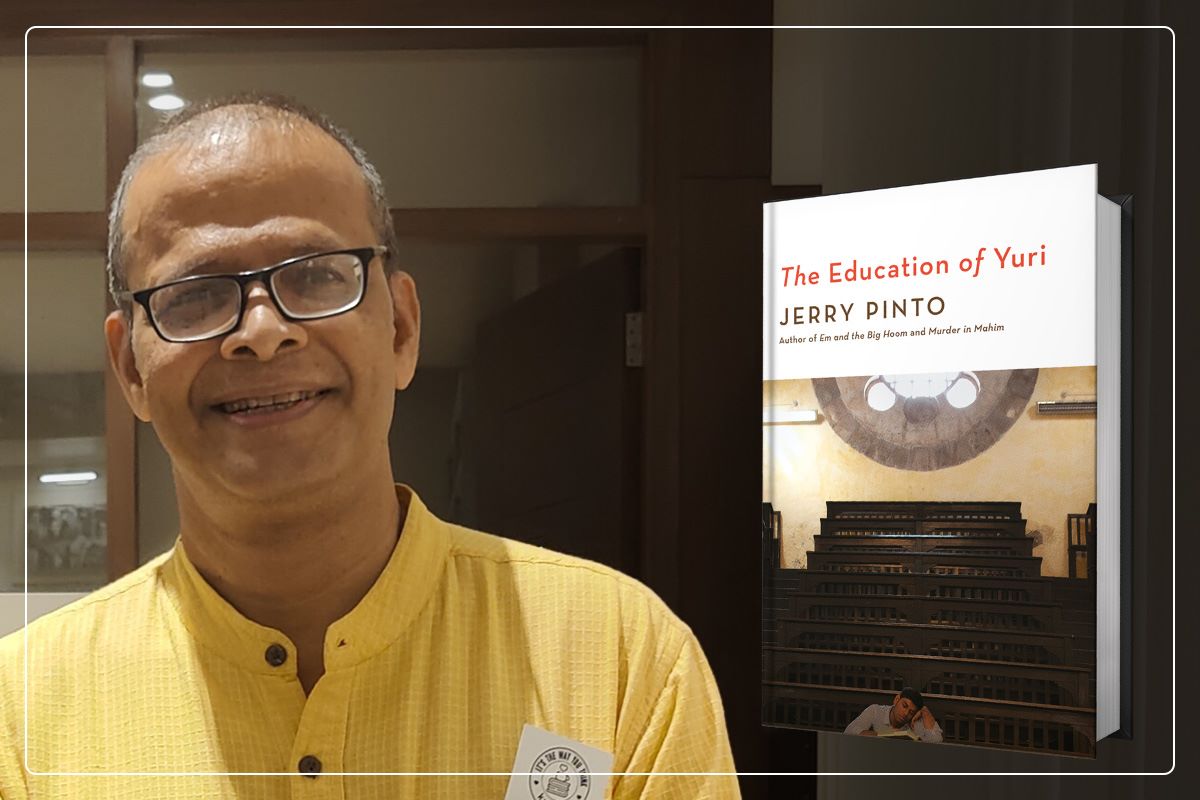

In Kunzum for the launch of his latest book, prolific writer and translator Jerry Pinto speaks with Paridhi Badgotri about existential writing, deconstructing stereotypes, and the relief he finds in translation.

Having a conversation with Jerry Pinto is a delight unto itself. His passion and profound thoughts on literature reminded me of why I love reading. My rendezvous with the writer and translator happened at Kunzum Jorbagh, where Pinto was launching his latest book, The Education of Yuri. I couldn’t resist asking him the most pressing questions about the field, and he was gracious enough to dole out his unfiltered thoughts without pretence.

Excerpts from a Conversation

Kunzum: Adil Jussawalla posited that The Education of Yuri is ‘the first Indian existential novel’. How does your novel compare to Western existential form?

Jerry Pinto: See, I think the Western existential form was born out of a crisis―and that crisis was the crisis of modernism, a complete collapse of belief in God and belief in the stability of society. In India, we’ve never had that problem because we’ve never believed in a unit to be a sort of God―and we’ve never believed in the stability of society. We know through experience―regular experience―that our world is fluid and that everything is subject to change. So, the only constant is change. Dealing with that, existentialism then majorly becomes a way of investigating the interior landscape in India, looking at what is happening in the sight and inside one’s head―and what is happening to one. It’s that moment when the interior becomes the exterior and the exterior becomes the interior. It’s like, “This is happening outside, what is happening to me?” And that’s why the constant conversations that you read, the things that I think of, are familiar to all of us who have heightened self-awareness, that you’re never very sure that what you’re doing is actually a reflection of what you’re thinking. So you’re in a constant dilemma about it.

Yuri, in the novel, starts out with the standard feeling of being underprivileged while being privileged. Through his life, he never probably has to worry about whether he is going to have dinner or not, or if going to college is a certainty. I think part of his education is literally to find out that there is much beneath him as well. When a solution of his problems is offered to him, he rejects those solutions because they are not his solutions.

Kunzum: You paint a portrait of 1980s Bombay in The Education of Yuri. What made you choose that era and what impact do you hope it will have in contemporary times?

Jerry Pinto: The reason we need to remember is because there are two ways of looking at memory, one is memory as a corrective and that old one that if you do not remember your history you’re going to repeat the mistakes of history. Again, Indian philosophy tells us that there are cycles, whereas Western growth models seem to have been as the arrow of time: things move straightforward. We know that we are spiralling, but the interesting thing about the spiral is that you may find yourself at the same place on the spiral―but at a completely different place because you’re moving in a circular pattern―through spaces. So, I think one of the ways of looking at the 1980s, or looking at the past, is also to recognise that there are eerie echoes in the present and that there are easily avoidable mistakes that we make. Eventually, there is a grand narrative of history that is unfolding around all of us―and this grand narrative makes some of us very uneasy and make some of us very joyful. We must not forget who rejoices in the history that we are making today. For both of these, memory is an important thing―and it plays a different role. Maybe, when we look back, one of the things that we do is try to process what we went through. And this processing is often forgotten—we often seem to think about just witnessing, we seem to think about gathering information. But processing is really, really important. And it is an ongoing process, it is not something that ever stops. A historian was asked recently what he thought of the Treaty of Versailles, and he asked, “Isn’t it too early to say?” But, of course, it’s too early to say―it’s probably too early to talk about the Egyptians, but what choice do we have? We’re gonna have to go out on a limb and start talking about it sooner or later. And the 80s were such an ugly generation, the ugly decade. Everyone talks about the 80s as a failure of a decade. I can see that, but I also have a great affection for those years and that’s why I had to represent the 80s.

About the impact it might have: one thing that one learns about the writing of a book is that it is infinitely mutable. It is not a steady fixed object; you might make it as a steady fixed object because you hold it in your hands but the first copy is the last time it’s steady. You know then that Pridhi (the interviewer) will read and make it another thing―and even if you forget it and you think it has no impact on you, two days later you’ll find that it is still staining you in some way, and those things are cumulative. So, this will be part of a whole narrative of different books that you are reading. You tend to think that your curation of narrative will give it a particular place; there is actually no such thing. And I would love to think of my books as something ‘dealing with’ or ’emphasising that’ or ‘foregrounding this’, but my own experience with each one of my books is that when a reader takes it, they make it their own―and that impact is something even a reader can’t quantify. Often, when I’m writing, suddenly a line from a book that I read 30 years ago starts happening under my pen. Sometimes, I leave it as a homage to the fact that we are not unitary and solitary individuals making books but we are forming literature in groups out of nowhere―we are the sum of our readings. So, this book will become the sum of other people’s readings, it will become one of the factors that will play into into the region. Someone told me that it’s about loneliness. I said, Yes. Then someone else said it’s about the futility of the middle-class. Indeed, it is also about the futility of the working class. Someone told me it’s about adolescent sexuality. Each one of these people brought their lens to the reading and therefore refracted my book. So, maybe the book is a kaleidoscope. You pick it up and it changes because your eye changes in the moment reading happens.

Kunzum: Language has always been inadequate in describing the human experience. How do you then, as a translator, transfer a text from one inadequacy to another and still maintain its essence?

Jerry Pinto: First of all, you’ve got to decide what the essence is. Like, why is someone coming through the door to smoke? And what is the word they want to put, so when it’s something like Baluta, which is a Dalit autobiography, you know that the majority of the readers of its translation are going to be privileged people from the upper echelons of society, who are, for whatever reason, looking to encounter another kind of guy. What the essence of that book is the life, but when you are doing something like Cobalt, which is about a young man and the siblings who fall in love with him simultaneously, does he play them simultaneously? Or does he simply, as an act of magnanimity, love them simultaneously? And why does he abandon them? So, a reader is looking for emotional tonalities of a certain company, right? And the relatability of that will be whether they find the plunging seat in that moment. Therefore, for me, it is [about] tone. Because once you get the tone of a book right, the reader picks up the tone too. Resonance among the readers is actually like the physics word―it is about frequencies matching each other. Soldiers marching with a certain matching frequency can bring down a bridge, so they break their frequency while crossing a bridge—to keep the bridge intact. If the tonality of the translation does not match the tonality of the reader, the bridge that I’m trying to build between two experiential sets of language, collapses. So, as an act of faith, you try to find the tone, you set the tone up, and then you pray that they cross the bridge.

Kunzum: You have often talked about how people have tried to put you in a certain linguistic position with respect to your socio-political identity. Did you want to defy that position by learning multiple languages to the extent of becoming a translator?

Jerry Pinto: If you have one dominant language in your life, any other reading experience becomes a translation. When I’m walking through the streets of Delhi, I rejoice that you have four different scripts on the same walls! For most people, looking at the signboards in Delhi will be a boring experience, but for me [it is] the experience of looking at four scripts! How lovely is that? We have only two in Mumbai. I think, in some ways, almost everything about language is a fascination [for me], that’s why I became a translator.

And these things that people say, ‘Oh, Romans Catholics are lazy’ and ‘They like to just sit and play guitars’ are just stereotypes―and you learn to live with them. Stereotypes are a serious business―and, of course, they have an element of truth, and, of course, they are false. I think challenging those stereotypes might also be part of the fiction writer’s problem, because as soon as I named somebody Caterina de Souza, you’re already thinking of what Caterina de Souza looks like—or if I name her Toral Shah, you already have another set of ideas. Now, if I’m playing into that, into that stereotype, my life becomes much easier as a writer, but if I am deconstructing it, I must work, I must decide how much work I’m going to put into that deconstruction and how many words are going to be taken to deconstruct. So, it’s a lot of effort that you’ve got to put into working with stereotypes, and acknowledging that they exist.

Kunzum: You have practised so many forms of writing: poetry, novel, children’s fiction, journalistic writing, translation. Which form do you enjoy most?

Jerry Pinto: Every time I pick up my pen, I’m hoping it’d be a poem. So, the writing is always—like a proper fountain pen—careful and cursive. And then I discover that it’s not a poem, 98% of the time. The words that coalesce the ideas are kind of encoded and performed inside the head. When that comes together on paper, most of the time it comes out as prose, and then I have to give a format to it. I sit to write a poem, but a little essay comes up. Then suddenly, it opens out into a story, then becomes a novel―then becomes a huge novel. I’d love to be writing poetry all the time, but it does not happen. And there are times when you wish you could make it happen, but I think if I made it happen, I would be cutting prose into short lines and pretending that it’s poetry. And I’ve seen enough of that to not want to do that. So, I allow the words the liberty to take the form they choose. The only thing that is an act of volition, therefore, is translation, where you have to sit down and say, ‘Okay, open the book and you’re now an 85-year-old lady who was writing an autobiography about living in Bombay; you are now a 40-year-old man who has come back from England and just had a wild fling with a Jew and is committing his thoughts.’ So, translation is actually the relief of being in a cage. When you have experienced higher quantities of freedom, and you’re very frightened and tired, you will retreat into the cage of translation, and you’re happy in that cage. But then, of course, it becomes constricting as all situations and you jump out again and go back into freedom.

Kunzum: What are the five books that you would recommend someone to read?

Jerry Pinto: The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki! The east―the Orient—invented the novel in the 11th century. Murasaki is talking about novels that her characters read, which are old fashioned. We’ve lost those and keep talking about Pamela by Richardson being like the first novel―no way! We had novels in the 11th century, and no one’s reading them. Genji is blue ink on purple paper―I love it so much! That’s my first all-time choice. The second is The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, because she’s delightful. And the third one would be—it sounds like one is kowtowing but it’s—The Mahabharata. It’s just enormous, It is immense, it is wonderful! And you have to give up everything and plunge in, because you just lose track of everything but it is wonderful to lose track. The fourth is Marcel Proust. There will be moments of intense rage, immense annoyance, intense problems with the solipsistic and narcissistic view of the world, but at the end of it―oh my god, you feel an achievement of climbing a mountain; you’re on the top and you put your tent and you find yourself going back to it. The fifth is a toss-up between Middlemarch by George Eliot, Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, and Anna Karenina [by Tolstoy].