Sheela Tomy’s debut novel, Valli, was shortlisted for the 2022 JCB Prize for Literature. In a JCB panel of the Jaipur Literature Festival 2023 last month, Tomy spoke about the importance of forests and its guardians. Kunzum wanted to know more about her environmental activism and bring her ideas to you, so we sat down with the author for an enlightening conversation. By Paridhi Badgotri

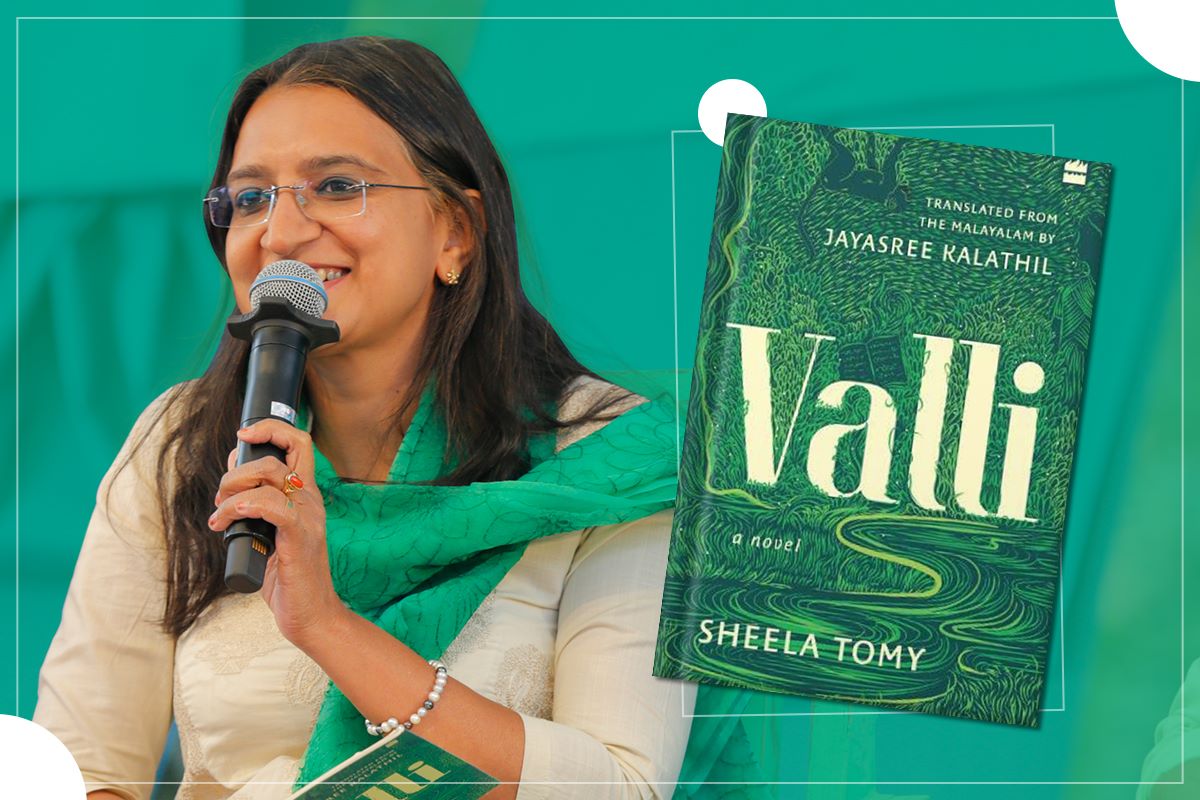

In a white kurta layered with a green dupatta, Sheela Tomy was the embodiment of the cover of her novel, Valli, as she spoke at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2023. Set in the Western Ghats in northern Kerala, the book paints a landscape shrouded in mist and mystery—forests teeming with the folklore of the indigenous people. Spanning four generations of people who call this place their home, this eco-fiction narrates the exploitation of their pristine land—by traders, colonialists, migrants from the lowlands, and the timber and tourist industries—and the resulting erosion of Adivasi culture, and their resistance. The author immortalised the script-less Paniya language by deploying its words in the Malayalam font, and the translator, Jayasree Kalathil, in turn, put the novel on English literature bookshelves.

As we cross these language barriers, Tomy makes us sit next to the remote tribes of Kerala and listen. It’s a much-needed perspective in these times of rampant deforestation, climate change, and social injustice. We spoke with Tomy about her influences, the script-less language she uses, the lives of the aboriginal communities she describes, the politics of land and much more.

A Conversation with Sheela Tomy

Kunzum: Valli refers to Gabriel García Márquez at three different places within the first 50 pages. What is the influence of Márquez on your writing and environmental activism?

Sheela Tomy: Márquez was one of my favourites since I started reading—in my teenage. And more than that, magical realism attracts me. Márquez tells us how to use memories, depict things and create new places like Macondo (the fictional home town of the Buendía family in One Hundred Years of Solitude). I was also very fond of Love in the Time of Cholera. And when I was designing Susan’s (Valli’s protagonist) bookshelf, I was thinking, She has nothing in her life except for her daughter and their books, so which books should appear in her library? And the first thing that came to my mind was Márquez… There is an influence in the structure of writing [as well], but I’m trying to escape that. Every novel, or every story, should be in a different form. So, in my second novel, I try to escape that writing style. Most writers are influenced by the books they read… You cannot say that I’m creating out of nothing. I didn’t learn literature after Class 10―I’m an engineering graduate. But the Malayalam skill that I acquired was only through reading; the words I use, I get them from my reading experience. [As for] social activism, it’s not from books but from life itself. I was born and brought up in Kalluvayal, the village mentioned in Valli, where half of the population consists of aboriginal people but they don’t own any piece of land. However, they were the first owners of it. We, the migrants, came later. When we go through the history of the land, we see how much injustice we have done to the aboriginal people of the land. So, I think I became an activist from the real life stories I heard. The struggles of the people, of the migrants who came from southern part of Kerala to Wayanad because of poverty and 1947… these are also important. I have heard a lot of stories of survival from my grandparents, from their parents—and people around me.

Kunzum: In Valli, you show how atrocities on lands and its people earns nature’s payback. What made you address the politics of land and wages?

Sheela Tomy: The title of the book, Valli, has different meanings in Malayalam. Valli is Earth, Valli is [also] wages. In my part of the world, the Adivasi people have to work for the same Jenmi (landowner) for the whole year―for a certain measure of paddy, which is called Valli. If Adivasi people break the contract, they are punished severely. This practice has been going on in disguise since 1970. They say that they (Adivasis) are not slaves and we (landowners) are giving them enough wages, but that’s not true… I think changes will come [eventually], because many children of the aboriginal people are getting educated and signing up for government jobs. I think the scenario will change in another decade. It is difficult to fight the corporates, and it is a struggle for the environment too, but I do have hope.

Kunzum: You have employed the Paniya language, a gothrabhasha that lacks any script. What challenges did you face in putting such a language on paper?

Sheela Tomy: Paniya people stay close to my house. I have contact with them since my childhood, but I’m not familiar with their original language. [To use this language] I took the help of a friend, Sarita, who reads news on a radio station in Paniya language. Whatever I wanted to express in the Paniya language, I wrote it in Malayalam and sent to her; she would write the meaning of the [Malayalam] words in Paniya language. We used the Malayalam font because Paniya is a language without script. This is how I managed to get the conversations, and for the songs, I did a lot of research. Many studies have already happened on Paniya songs—they have a rich vocal tradition. I took the support of those researchers, especially of the books written on Paniya songs and folklore.

Kunzum: Why did you choose to write in a language that you didn’t know?

Sheela Tomy: It is a dying language, someone should stand up for a language that’s getting lost. A language is not just for communication but also culture and history. So, I supported the cause in the way that I could. It would have been easier for me to write in my own language, but it would not have been the right thing. Paniya is the language of an aboriginal community. Kerala is known for its high literacy rate, but I wonder if they include these communities. A lot of them go to school, but they sometimes drop out because they don’t know the languages taught in school. They feel inferior because in schools they don’t teach things that are related to them.

Kunzum: Did you receive any reactions to this book from any indigenous communities?

Sheela Tomy: It was well accepted by them. When I was writing, I was very worried about doing justice to them. I’m from a migrant community, and migrants took over their land—our ancestors came to Wayanad for survival. This politics of the land is very complicated. Only through education is resilience possible.

Kunzum: Which books would you recommend to our community?

Sheela Tomy: Márquez! I love all of his books. The book I recently read was Shashi Tharoor’s Ambedkar: A Life. And people should also read Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste. These are the books that everyone should read.