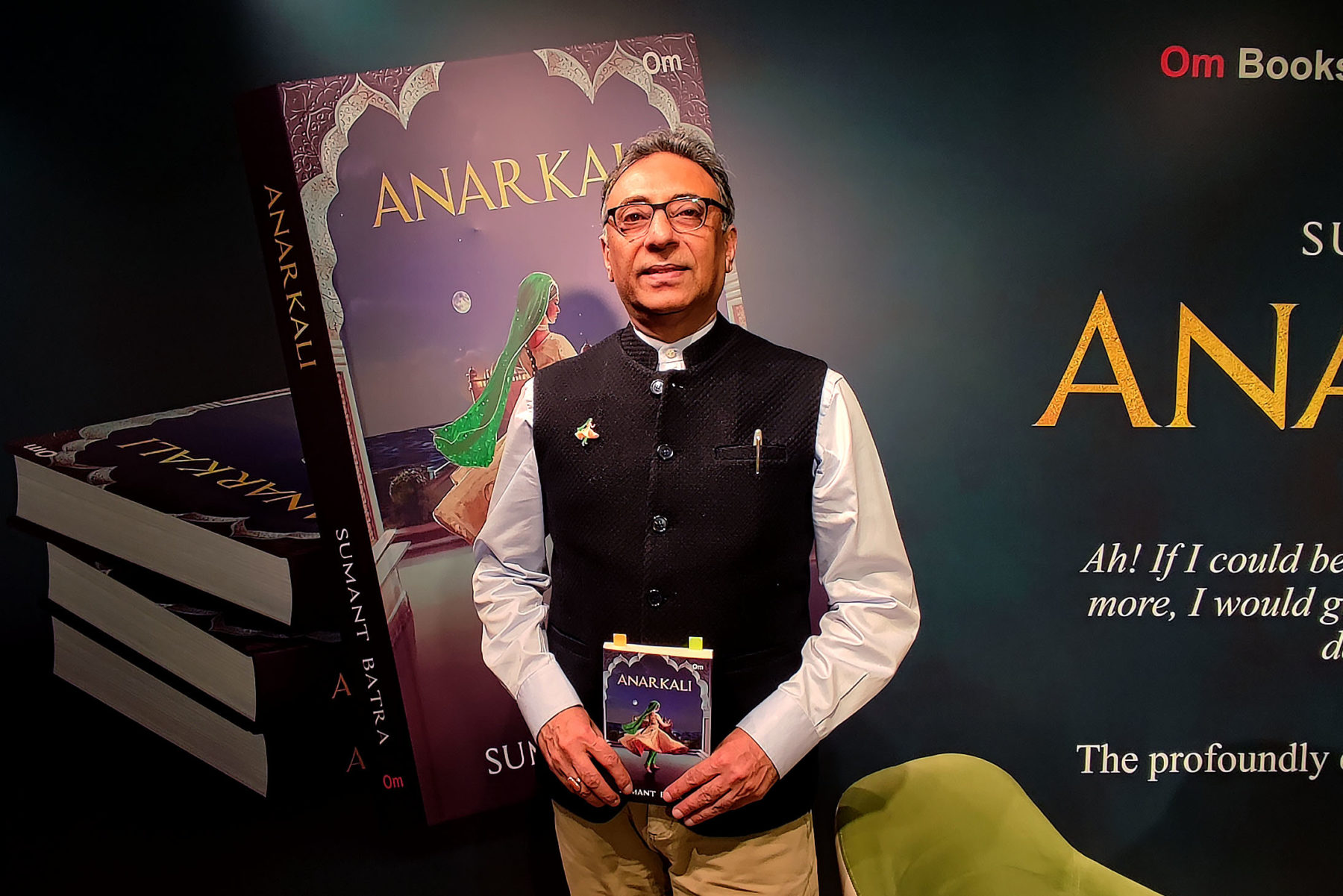

From forgotten stories and tales told by the tour guides at Fatehpur Sikri, author Sumant Batra traced the life of the legendary dancer Anarkali. He tells Kunzum Review how his book Anarkali came into being.

Bhavneet Singh Aurora: It is not every lawyer who gets into writing about literature. How did you get into this?

Sumant Batra: Lawyers do write literature, but normally they write what you may call as literary legal literature. I have been a bit unconventional in that I have been interested in literature which is other than legal, although I have a lot of books that I’ve written on law as well. It may come as a bit of a surprise to many people that as a lawyer I’ve written something which is a historical fiction, and not only a historical fiction, but something which is a very passionate love story. You could say that I somehow break the stereotype in a way.

BSA: Your book Anarkali is very rich in historical detail. How much research went into it?

SB: The research took about three years and I traveled extensively to Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Allahabad, even Lahore, because the entire book is set in primarily these four locations. And although it’s a fiction, but it is set in a historical backdrop, which is entirely accurate when it comes to dates, period, locations, culture, people, way of life and some other details. That required research. But Anarkali itself is something which required a lot of research too, because while she is a very popular figure in history, there’s surprisingly little written about her. There are accounts in history, in films, over a period of almost 100 years right from the silent era to the talkies, on Anarkali, but they are all based on the same narrative, so I didn’t really get much out of watching those films. There is some reference to her in history and also surprisingly, in accounts of foreign travelers to India in the Mughal era, and later on, which threw a lot of light on Anarkali. But ultimately, you know, I still had room for a lot of creativity, my imagination, my own way of giving her an identity, a name, a life which none of the writers or filmmakers have ever thought of, or even if they did think of it, at least executed it in their creativity.

BSA: How did you decide to write about Anarkali?

SB: That is a bit of a fascinating story. It happened on one of my many trips to Fatehpur Sikri where one of the tour guides at Fatehpur Sikri fort told us that this is where Anarkali was bricked alive, but actually Akbar allowed her to escape through a tunnel which opens somewhere in Delhi and he would give you a piece of a story about her. I found it very hard to believe. We were young at that time. I was somehow intrigued and I questioned and challenged his account. How can one even imagine that there would be a tunnel? I said it’s a figment of his imagination and he got very offended. He said ‘look, this is our truth. If you have anything better, accurate or different, why don’t you tell us, but don’t belittle our account of her because that’s what we’ve learned and been taught for generations and we’ve been telling people.’ I saw a point in in his getting offended by my questioning of his account because I was doing it just because it didn’t appeal to me, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it would not have happened that way. And that set me on the task to do my own search for the real story of Anarkali. It stayed in my mind for 8 to 10 years. One fine day I decided that I should actually take it up as a story which I should tell and that is how it manifested into this book.

BSA: During the course of your research for the book, did you come across any startling facts which you have not mentioned in the book?

SB: I think one of the first and most obvious things for me to discover was what was her real name? Because Anarkali – as she was popularly known – was a title given to her by Emperor Akbar because she was so beautiful. He named her after a pomegranate bud because he found her to be a very, very beautiful woman. But that was not her real name. And what I found is very surprising that in all the accounts that one had read, even the play that Imtiaz Ali Taj wrote in the 1920s, her name is not given; her an entity is not given. That actually led people to believe that she never actually existed, and that she was just a creation of a myth or a legend, or a figment of imagination of creative people, or oral storytellers. But ultimately, one of the things that I was able to put together was her real name. Although I still believe there are two names that came forward, but Nadira Begum, which I believe is something which I could safely say, was her real name. So that was a revelation for me.

The second was that everybody agreed that she was a dancer. She was a very good dancer. And the fact that Mughal-e-Azam and Anarkali are actually all built around some dance episodes, and they’re very telling dance performances, because the lyrics and the dance choreography, the costumes, the sets made them very grand. But the fact remains that she was a dancer and how she became a dancer, a Kathak dancer. For someone who came from a very different culture, from a foreign country, how did she learn Kathak? How did she become such a passionate dancer that she was invited to perform in the Royal Court because not every artist would get that honor or opportunity then. You really needed to be an extraordinary person and dancer and Akbar was someone who was known to be a patron for dance and his own understanding of Indian dance forms, cultures, arts was phenomenal. He could make out the difference between an ordinary and an extraordinary dancer. So she had to be an extraordinary dancer. How did she learn that dance? Where did she learn that dance? She was a performing art dancer. She was not a nautch girl, as the British would ultimately name any person, any dancer who performed, whether at the kothas or tawaifs, they were all performing artists in that sense. And they would normally not perform in public. They would perform for very select patrons of art. To me, I think that is the second most important, I would say, outcome of my research.

BSA: How satisfying was it when you found these two nuggets of information?

SB: More than it being satisfying, I think it was overwhelming. For me, Anarkali became a very passionate project. It started as something which was a search for some answers, a story, but on the way I think I fell in love with this whole project. And for me anything that came across as something which added value to the book, to my task, to my story, became something which I was always very gratified by. For me, therefore, there are a number of things. But more importantly, if I may say, ultimately I think my book, when I read it as a final product, threw up the fact that this was a story about the state of mind of 3-4 people. Why did they end up in that state of mind and how that state of mind affected their decisions, their relationships, their behaviour, their decision, their conduct, their attitude, all that to me, I think is something which I found to be a very human aspect of the book that every character tells the story of the same person as something which in a way tells the emotional, psychological and different shades of human behaviour.

BSA: At times, did you find the research and the writing of this book somewhat difficult?

SB: I think the only difficulty was to be able to find the time. I wanted to finish it much earlier, but my professional commitments are very demanding and I was not able to devote as much time to writing as I was able to for the research. So the only disappointment that I had, or I have, is that this book could have been done about 2-3 years ago had I found the time. But I don’t have any regrets though, because even those 3-4 years were well utilized. They were used to do other things of which I’m equally proud of. Destiny probably works the way it works. Everything is just trying to happen in a particular way at a particular time. God has his own ways.

BSA: Is there a particular chapter in the book on our colleague that you are extremely fond of?

SB: I would say it’s hard to narrow down to two, but there are two chapters which I believe will resonate with passionate, intense dancers quite a lot. One is the “Drowned in Dance” chapter, which was one of the toughest chapters to write for me because I am not a Kathak dancer myself and have no formal education or understanding of the Kathak dance, how the dancers feel, how they perform, how to even sort of explain that dance performance. That chapter is about a rehearsal which Nadira does in her room and is being watched by her aunt and it expresses the feeling of an aunt who herself is a dance teacher. The other chapter I would say is “An enduring passion”, which expresses Anarkali’s feeling at the time when she knows that she’s going to die, she’s going to be bricked alive and what is going through her state of mind at that point in time, about her family, about her love, about her decisions, about the afterlife. These are two particular chapters which I believe are emotionally very, very strong and powerful. I hope the readers will enjoy these two chapters alongside the others in the book.

BSA: If Vishal Bhardwaj, who is going to be introducing your book today, if he were to make a movie on this book, who would you like to see as Anarkali?

SB: That’s the most difficult question because I don’t think anybody can even imagine anyone else other than Madhubala as Anarkali. I think she is a benchmark which is hard to meet. We have a celebration of the book happening on the 17th and there is a Kathak dance performance happening as well. And we, including the artist who is coming from Pune, decided that she should actually dance with her face covered in a veil because we would like everyone to continue to imagine Anarkali and not see her face. And that is why if you see the cover of the book, it has a side profile. We haven’t shown her face because we just couldn’t gather the courage to give her that beauty because I don’t think anybody, any artist can do justice to that.

BSA: Anarkali is done, what next?

SB: I’m working on three books at the moment. One is something to do with law, but it will have a global appeal. It’s not really legal, but is meant for people, for economists, for socialists, psychologists, even students of history. It’s a very different subject, never been written about before. And it requires a lot of research of ancient texts. That’s one book. It will probably take about 11-12 months more. We’ve done a lot of research on that. One of my colleagues is assisting me on that. There’s another book that I’m working on, which will probably come out first out of the three. It is also a historical fiction, but very different from Anarkali. It’s not centered around a particular character, it is of a particular era, and again it has global appeal and I don’t think it has been written about at all. At least that’s what my research in the last six months shows. And I’m very excited about that, but that requires, tremendous research, too. And the third book on which we are working and which requires about a year and a half of research, is also an episode from history but it’s an episode of modern history, which I’m co-authoring with someone. It’s about something that happened in the last 50 years, after Independence, so we’ve heard shades of that in history, but nobody knows about it. It hasn’t been written about much, but I believe it’s a very important topic to bring out the pride of this generation. These are the three that I’m working on, all very different and that’s how it’s been for me. From Sanjeev Kumar to Indians before that, I try to do a different subject every time I start writing. My first book was actually a book on poetry.

BSA: From poetry to writing about Indians, then a biography and now Anarkali. Wonderful.

SB: It’s far more consuming in that sense because you know you don’t get the benefit of your previous research and knowledge on to the next work or even the profile for that matter, because people who like to read, for example, historical fiction, they would get disappointed. And also, I would not be able to sort of build on that particular category of readers which become natural buyers for your book, but I guess you know there are things that I do for myself. So that’s what motivates me, so it’s important for me to continue to do what I believe is something that will make me happy.

Pick up Sumant Batra’s Anarkali from any Kunzum store or WhatsApp +91.8800200280 to order. Buy the book and the coffee’s on us.