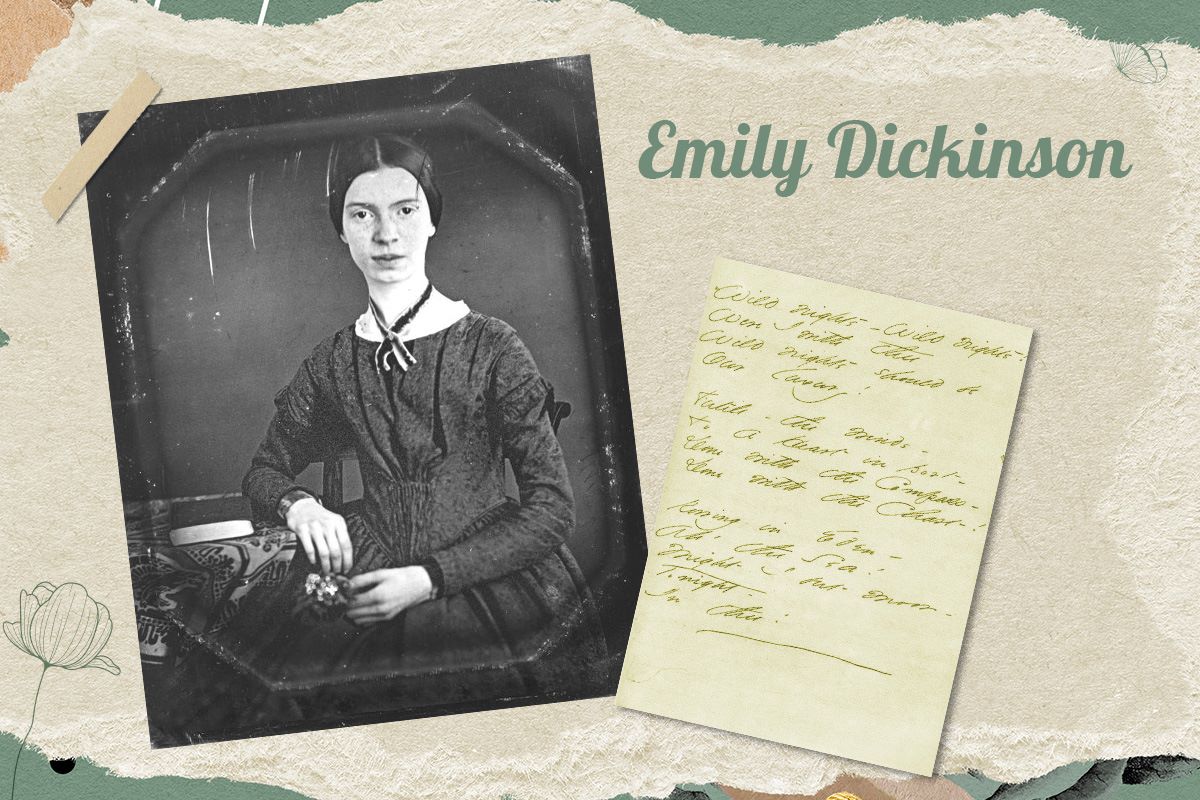

Emily Dickinson is an icon of American Literature whose genius was recognised, unfortunately, after her passing. Her original poems leave you in a state of flux—forced to ponder over the abrupt and fleeting thoughts of the poet. By Paridhi Badgotri

For the uninitiated, Emily Dickinson’s poetry can be disorienting due to its inventiveness—abrupt images, and oddly placed capital letters, dashes, and lines. From imagining death as a lover to representing the travails of being a woman in 19th-century America, her poetry does many things but mainly expresses the intense emotions she went through during her singular life. Dickinson’s desire to be a poet was constantly suppressed by the patriarchal conventions of her time. It was only after her death that bits of her poems were discovered and published—to widespread acclaim.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don't tell! they'd advertise – you know! How dreary – to be – Somebody! How public – like a Frog – To tell one’s name – the livelong June – To an admiring Bog!

One of the distinctive features of Dickinson’s work is that she did not give titles to her poems. This curious absence of labels seems to suggest that her poems are unfinished, like a thought that keeps on developing and emerging from the previous one and, thus, cannot be named. The inconsistence of the human thought process is also acted out on paper. Our thoughts rarely flow in a streamlined fashion, after all. Her externalisation of this imperfect mental process makes her poems unique for her time. The various dashes that she deploys, seemingly abruptly, may depict halts in her own train of thought.

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading – treading – till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through –

Dickinson spent a large part of her life in social isolation, not leaving her home for long stretches of time. It is no surprise that her poems are written in a manner that mimics the way the mind converses with the self, deducing a line from the previous sentence. For example, in the following poem, when Dickinson makes a statement about her present state ‘being comfort’, it is deduced that the ‘other kind’ is ‘pain’. Further, she goes on to say, ‘But why compare’, suggesting an extension of this internal monologue.

I’m “wife”—I’ve finished that— That other state— I’m Czar—I’m “Woman” now— It’s safer so— How odd the Girl’s life looks Behind this soft Eclipse— I think that Earth feels so To folks in Heaven—now— This being comfort—then That other kind—was pain— But why compare? I’m “Wife”! Stop there!

Putting down her troubling thoughts on paper gave Dickinson peace of mind—and a reason to live. She once famously said, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold [that] no fire can warm me I know that is poetry.” She wrote thousands of poems despite her life’s limitations, and nothing could alleviate her pain except the literature she read and wrote.

Before I got my eye put out I liked as well to see— As other Creatures, that have Eyes And know no other way—

Dickinson’s vivid imagery, mixed with a narrative of her internal thinking, is a conscious effort to express herself but not to reveal the whole. As she once wrote, “The Truth must dazzle gradually / Or every man be blind —,” Dickinson plants a seed of ambiguity in her work so as not to blind us with its horror. Pick up The Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson from a Kunzum store to delve deeper into her work.

1 thought on “Reading Emily Dickinson: How the American Simulates the Irregular Process of Thinking in Her Poems”