An art curator and writer experiences a peculiar detachment from the world that allows her to observe it closely. As is often the case, she finds company and resonance in a book—Exteriors, written by French Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux. By Arushi Vats

There’s a certain kind of loneliness that settled into my body at the onset of middle age that’s difficult to pin—it’s not the joy of solitariness or the pain of separation from the world. It’s somewhere in the middle, a tacit acceptance of a truth long rustling beneath the skin—there are moments of spectacular belonging within the vast tracts of life spent feeling always a step removed from the world, trailing a beat behind its proceedings. I remember Maggie Nelson’s note in Bluets: “Loneliness is solitude with a problem.” Fair enough—but there are states of mind between loneliness and solitude, pleasure and pain. After all the feelings have been felt, disenchantments have encrusted into wisdom, dreams have been whittled through the funnel of possibility, a form of loneliness that is devoid of desolation and tinged with wonder presses in.

It’s not a wounded retreat or indifferent withdrawal from the world or a tense state of alertness. It is the loneliness of living in the everyday, repeating that which makes up the ordinary of your life, not expecting grand encounters or revelatory light to fall from the sky. In this kind of loneliness, there is a heightened awareness of the world around me—the texture of the sky, the colours of the season, the billboards, the gravel, the windows of houses one is passing. The mind seeks scenes to read: close enough for observation but sufficiently at a distance so as to not disturb the order of inner sentiments.

I remember Maggie Nelson’s note in Bluets: “Loneliness is solitude with a problem.” Fair enough—but there are states of mind between loneliness and solitude, pleasure and pain. After all the feelings have been felt, disenchantments have encrusted into wisdom, dreams have been whittled through the funnel of possibility, a form of loneliness that is devoid of desolation and tinged with wonder presses in.

The closest I can come to describing this is: circumspective curiosity. Observing at a cautious remove from the proceedings. In my commute and other chores, I find myself paying attention to strangers in the metro or the market—catching snippets of their conversations, noting which books they are reading, taking a temperature on how exhausted everyone is. It’s a delicate act to not stare at or offend a person, but to observe a crowd; groups of people—the way they navigate their bodies in conjunction with one another, their voices overlapping and interrupting one another. The swell of chatter rising and the hum of silence; touched by slumber, our slumped forms forgetting boundaries of propriety. It is a form of being in the world without any encumbrances. I am merely one in the space of many, and in their being here, however fleetingly with me, they are helping make up chunks of my world by sharing with me the usual hours that arrive without fail, the hours that must be lived without fault, in the comfort of routine.

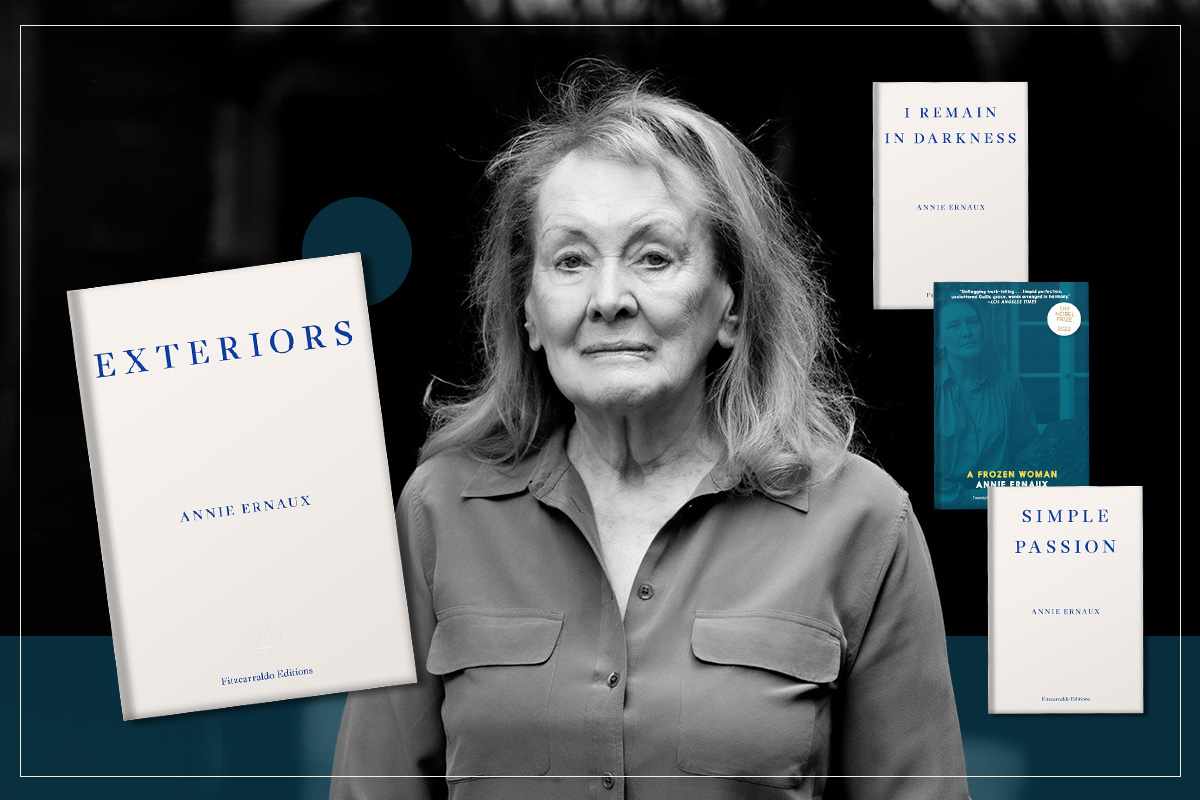

I’d chalked this proclivity up to my usual oddities, the shard-like qualities that keep me at an arm’s length from the world, and an undying wonder which has made me its devoted student. I was tremendously excited to chance upon Exteriors, a book by Annie Ernaux comprising solely the overhead snippets, the glances of short durations and ephemeral observations excerpted from seven years of her time living in a new town that had sprouted outside Paris and where she lives till this day—a recently inhabited town that Ernaux describes as having no memory of its own. Ernaux begins this book with a simple mission: “I felt the urge to transcribe the scenes, words and gestures of unknown people whom one meets once and whom one never sees again…”

Working through her diary, Ernaux assembles fragments of conversations heard on trains, graffiti, news items, everything sourced from the world outside the orbit of her private life; everything that is brief and existing only in the span of a moment. These are irregular passages filled with narrative starts, and Ernaux leaves the fragment open, we don’t know the before or the after of the scenes we are being presented with, and neither does Ernaux. There’s something indescribable about this partial knowing, a suspended state of reading the world, where the urge to fill in the blanks or figure a conclusion never sets in, there’s simply attention to perspective and description to render that moment sharply alive on the page.

It’s filled with lines like these, which could describe any number of days or any number of towns with buildings in glass and chrome, because it understands how much atmospheric elements influence the experience of day: “On a sunny day like today, the seams of building lacerate the sky, the glass surfaces radiate light.” And there are lines that sting like astringent for their closeness to life: “‘Go home!’ the man tells his dog… The same expression used throughout history for children, women and dogs.”

“I felt the urge to transcribe the scenes, words and gestures of unknown people whom one meets once and whom one never sees again…”

—Annie Ernaux, Exteriors

Exteriors is a rare book in Ernaux’s bibliography, which has otherwise drawn extensively from the personal, the domestic and familial. Unlike other writings of Ernaux which are episodic, whether it is narrated, such as A Frozen Woman, or recounted, such as A Simple Passion, Exteriors retains the quality of snapshots—flashes of light that extinguish at great speed. Ernaux begins the book by confessing that this commitment to looking outwards was a deliberate attempt to think past the illness gripping her mother at the time, and to “ease the grief” of watching the memories of someone you know and love slip into blankness, and Ernaux writes with precision her witnessing her mother’s Alzheimer’s in I Remain in Darkness. With Exteriors, Ernaux feels that in some ways by noting these observations in her diary, she was retaining her own connection to a world which was receding from her mother’s consciousness. Where I Remain in Darkness is a study in the social shame attached to illness, Exteriors is a coping mechanism, a way to escape the circuit of pain and incomprehension that personal tragedy holds. It feels illicit. Late in the book, Ernaux identifies what this particular mode of pleasure is: “I am visited by people and their lives—like a whore.”

It is a rare book where we also see Ernaux by herself, not defined in any weighted relation to another, and accessing her life solely through her notes and observations. It is Annie alone, the person she is when not a daughter or lover, but simply, commuter or neighbour. A spectrum of emotions, from guilt to pleasure, escape, presence, and even pain kept at abeyance, sediment beneath the surface of Exteriors, which reminds us that however alone we may be, as Ocean Vuong writes, it is “still time spent with the world.”

Arushi Vats is a curator and writer based in New Delhi. She is the recipient of the Momus – Eyebeam Critical Writing Fellowship 2021 and the Art Scribes Award 2021.

(Kunzum stocks all of the Annie Ernaux titles mentioned in this article. You can visit any of our bookstores or place an order on WhatsApp.)

Related: The Year of Magical Thinking: How Reading Joan Didion Helped Me Cope with Loss and Articulate Grief