Engulfed in stories from the West since my childhood, I placed Western authors—their writing style, voice, and elite experiences—on a higher shelf until I discovered that, like many others, I was suffering from a colonial hangover. By Paridhi Badgotri

Growing up, my book pile never missed a classic by Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Oscar Wilde, Jane Austen, or Charles Dickens. There is no doubt that the European continent has produced some of the greatest literature of all time, but the reason behind its popularity is more than just excellent writing. Our reading choices are unconsciously influenced by socio-political factors. And historically, Eurocentric powers have often dictated what ought to be regarded as good or bad literature. The fact that many of these powers were also colonisers helped the cause.

As a naive literature student studying in Edinburgh, I was fascinated with the lives and works of Western authors. It was only after postcolonial writings were introduced in my academic course that I reckoned with my biases. Before going into what constitutes postcolonial literature, one needs to deconstruct the term itself. The ‘post’ in ‘postcolonialism’ does not necessarily imply that colonialism has ended entirely; it has a clear and persistent legacy. We still suffer from a colonial hangover. In other words, European colonialism might have ended in terms of physical occupation in the 19th and 20th centuries for most countries, but the colonised peoples still struggle with impoverishment and Western dominance over societal discourse. It lingers in ideologies and practices that assume supremacy of the colonising culture. Consequently, postcolonial literature not only discusses the exploitation of the colonised and their native lands, but also covers their resistance to the cultural legacy of colonialism as well as stories that engage with the process of decolonisation.

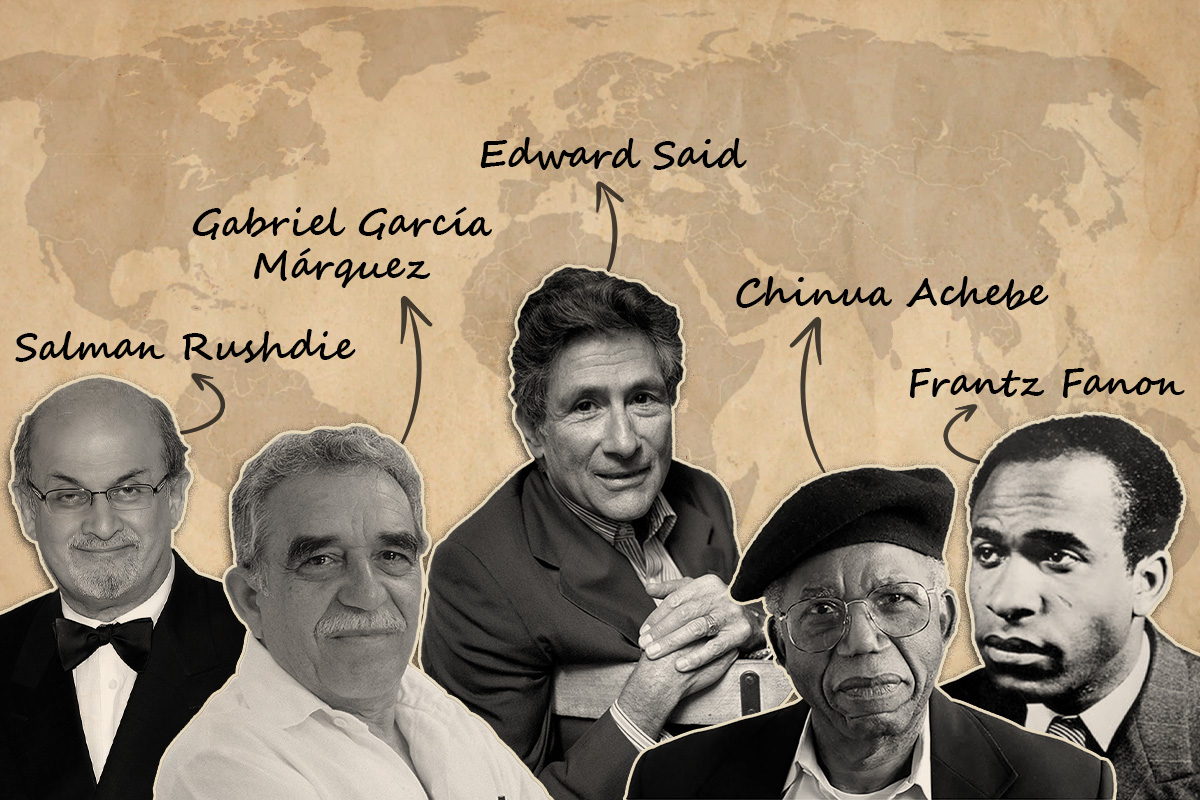

The first book one should read to understand postcolonial literature is Orientalism, written in 1977 by Palestinian theorist Edward Said. It was through this collection of essays that my mantle of European literature started to crack. Said points out how the West has constructed stereotypes of the East for its own benefit. Eastern didn’t get a chance to represent themselves historically, because they were subjugated by Western hegemony and automatically became the other. This changed with a wave of postcolonial writers like Chinua Achebe, Gabriel García Márquez, Pablo Neruda, Salman Rushdie, and Derek Walcott, who presented the world through the eyes of the colonised.

Decolonisation is important for overcoming our colonial hangover and bringing non-Western literature to the forefront. In his book, The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon rightly posits that “imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well”. In today’s world, postcolonial literature has gained prominence but narratives from non-Western countries are still very much restricted to their respective countries. In an active effort to decolonise my mind, I now consciously explore the wide variety of non-Western literature out there and forage esser-known books hidden beneath the blanket of Western literature—while also appreciating the beauty of the blanket.

Kunzum stocks a great collection of home-grown literature as well as underrated books from around the world. Start your 2023 by picking up a book that decolonises your bookshelf.

Related: Book Review: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams