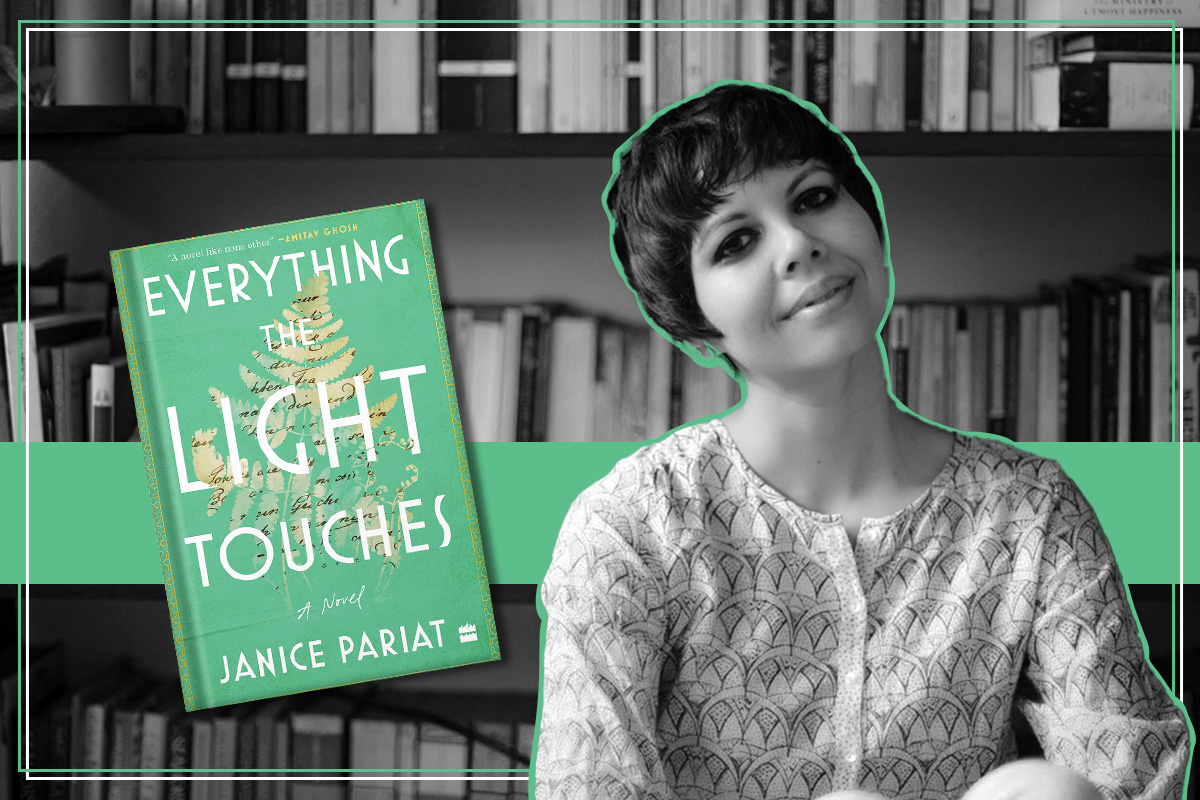

Author Janice Pariat speaks to Kunzum about her latest novel, Everything The Light Touches, and the tussle at the heart of it, her affinity for botany, adoption of erasure poetry, literary influences, and what she calls ‘the relationship trilogy’. By Sumeet Keswani

Literary accolades are not new for Janice Pariat, who won the Young Writer Award from the Sahitya Akademi and the Crossword Book Award for Fiction in 2013. Her debut short-story collection, Boats on Land, novel, Seahorse, and novella, The Nine-Chambered Heart, had already placed her among the constellation of Indian literary stars to watch out for. Her latest novel, Everything The Light Touches, does justice to that reputation by tackling universal issues of division and categorisation with the simple metaphor of botany—and two scientific yet conflicting ways of looking at plants.

The book follows four characters across centuries and continents as they embark on journeys of discovery and transformation. There’s Shai, a young Indian woman who goes back to her home in the Northeast and encounters indigenous communities and their traditional ways of living that continue to align with nature; Evelyn, an Edwardian student at Cambridge who gets inspired by Goethe’s writings and goes on a quest for a mythical plant to the forests of the Lower Himalayas; the famous botanist and taxonomist Linnaeus, who led an expedition to Lapland in 1732; and Goethe, who formulated his groundbreaking botanical ideas on a tour of Italy in the 1780s. It’s a whirlwind of a book that’s been 10 years in the making, Pariat says.

We sat down with the writer to know more about the characters, settings, metaphors, and meanings of her wonderful book. Excerpts below.

A Conversation with Janice Pariat

Kunzum: The Nine-Chambered Heart explored the themes of identity and perception, Seahorse retold a Greek myth. What made you centre this book around botany?

Janice Pariat: Everything the Light Touches doesn’t centre around botany as much as it employs botany as a metaphor to explore ways of seeing the world—the particularly Linnean mode of perception that relies on separation, distinction, labelling, and categorising, and the Goethean way that gently urges holisms, unity, connection, and the use of imagination. So while we meet many botanists in the book, the focus is on their practice and what that reflects about the generation of knowledge (particularly in colonial times), and how this has had devastating effects on our relationship with the natural world. I’m interested in the intersection between botany and philosophy—how you see a plant (whether as a whole or a collection of parts) is how you see the world.

Kunzum: What’s the origin of your own fascination with botany?

Janice Pariat: I always enjoyed it as a subject in school until I was forced, by a particularly ridiculous education system, to choose between “arts” and “science” and had to leave it behind in choosing the humanities. This is precisely what the novel, and perhaps all my writing, rails against. The need to fix and categorise, to splinter, to divide. I don’t think I returned to botany in any meaningful way until I began my research for Everything the Light Touches, a decade or more after I was done with school. But I returned in a new way, a Goethean way, that re-taught me the subject, that made me look at it with new eyes. I also started spending a lot more time in the outdoors, in forests and open spaces, following rivers and chasing waterfalls. I tended a small garden. Kept some house plants alive. Noticed more. Began conversations with green living beings, and learned, in all this, to be a humble observer, note-taker, storyteller.

Kunzum: You said at the book’s launch that the first character you came up with was Evelyn—10 years ago. What made you take up her story a decade later?

Janice Pariat: Evie, as a character, stayed with me all those years—she didn’t go anywhere. It took that long for my research for and writing of Everything the Light Touches to be done.

Kunzum: There’s a lot of travel and discovery in each character’s journey. And you wrote a lot of this book during the pandemic-enforced lockdowns. What were the challenges of doing this? Were there any benefits?

Janice Pariat: By some stroke of luck, I managed to travel to libraries in London, to Linnaeus’ home in Uppsala, to Goethe’s apartment in Rome, all before the first lockdown. In fact, Italy shut while I was still in Rome, in March 2020, and making my way home to India from there is a story for the ages—but I’ll save that for another day. Sadly, the places I couldn’t visit were the remote villages of the South West Khasi Hills, where my character Shai travels to from Shillong—this in fear of accidentally carrying the virus to these isolated areas—so I had to rely on reportage, interviews, and documentary footage on the uranium mining issue in Meghalaya from other sources. In retrospect, the benefits, though, were numerous, and I say this acknowledging the privilege of having a home in which to spend the lockdown. I had time to tend to my small garden. To be still. And perhaps in that stillness write about movement and travel more meaningfully, more thoughtfully, and even with some longing.

Kunzum: Do you subscribe to the Linnean or the Goethean way of thinking? In other words, when you’re travelling, do you like to know the names of things or does namelessness help in seeing them as parts of a whole?

Janice Pariat: This is tricky. How much easier to say I subscribe to Goethe’s way of seeing the natural world and be done with it. But I also acknowledge it’s more complicated than that—that this tussle between the two exists precisely because there is value in allowing for understanding and clarity to spring from names. It’s safe to say I disagree with method then—in how Linnaeus places himself in a position of power and entitlement when he says “only after a thing is named is it known” whereby Goethe suggests we allow for a green living thing to reveal its name to us, to begin a conversation with it as subject not object, and disrupt the hierarchy set up by traditional ways of “doing” science.

Kunzum: A part of the book is written as erasure poetry. Tell us more about this approach and why you adopted it.

Janice Pariat: My idea was this—that within a novel that hoped to question our penchant to categorise, I would insert, amidst the prose, a section of lyric narrative, one told entirely through verse, and more specifically, Erasure. Erasure poetry is crafted using an original pre-existing text, and mine would be Linnaeus’ Lachesis Lapponica or a Tour in Lapland, translated in 1811 by James Edward Smith. The journal entries would serve as material for poems—not in the more tangible way that Erasure can function (for example, “blacking out” or visibly obscuring portions of the text to craft a wholly new work from what remains) but in a gentler, less intrusive manner. To take Linnaeus’ words and place them in a poem, sometimes teasing them into a sestina or sonnet form, or allowing them to work in free and blank verse. So while what emerges eventually are new poems, these new poems are constantly haunted by the old, by the original text—in the same way that I believe the world is still haunted by Linneaus’ way of seeing.

Kunzum: Shai has similar roots to yours—and a similar urban displacement—and is in search of a semblance of home. Where do you, Janice, feel at home?

Janice Pariat: A few years ago, in the before-Covid times, I would possibly have given you a more itinerant answer—the kind that voiced how, in my life of much movement and shifting, between cities, nations, continents, wherever I placed my suitcase was where I felt at home. Less so now, I think. Perhaps because I’m older. Perhaps because the pandemic-ridden lockdowns did shift something within us, and make us question where we truly wished to be. I live between Delhi and the hills of Meghalaya, but more and more I am drawn to being back in Shillong—to exploring the stories of a place where I have, like Shai in Everything the Light Touches, been told to move away from to be a “success”. I am drawn to these storied landscapes, to the histories that have lain hidden for so long, to people and community that I feel I am only now beginning to know. In the book, Shai has a revelation about how “here is everywhere” and in truth I feel similarly. That, like a tree, we need to root, so we may reach up and away towards the sky.

Kunzum: Which writers have most influenced your craft of writing?

Janice Pariat: Jeet Thayil for his meticulous rhythmic pacing of sentences, Shirley Jackson for her precision and startling imagery, Robert Macfarlane for his immensely rich vocabulary when writing about the natural world, Madhuri Vijay’s astonishingly rigorous sentences and story structures, the gorgeous simplicity and power of Easterine Kire’s poetry. Yet alongside all these and more, for I couldn’t possibly recount all my debts of gratitude here, the storytellers in my life from Shillong and the hills of home—most of whom could not read or write, but who told marvellous stories. Indeed my deepest “literary” influences are those to whom I listened, who wove stories out of thin air, who kept us captivated by the fire, who thrilled and enchanted us evening after evening. My craft of writing owes so much to the craft of telling stories.

Kunzum: If you were to recommend five books to our reading community, which would they be?

Janice Pariat: Pranay Lal’s Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent, Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Robert Macfarlane’s Underland, Sharmistha Mohanty’s Extinctions. Each of these in their own way offers us long perspectives, deep contexts, and geological timelines that teach us humility and gratitude, that place us and our species right where we belong, in the small, the fleeting, the joyful, the miraculous.

Kunzum: What are you working on next?

Janice Pariat: The second book in what I’m beginning to think of as “the relationship trilogy”—with the first “instalment” being The Nine-Chambered Heart.