In a world tripping over its convoluted reasoning and rigid rules, children’s fiction can open new doors of thinking. The Little Prince and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are two such books that will turn your adult worldview upside down. By Paridhi Badgotri

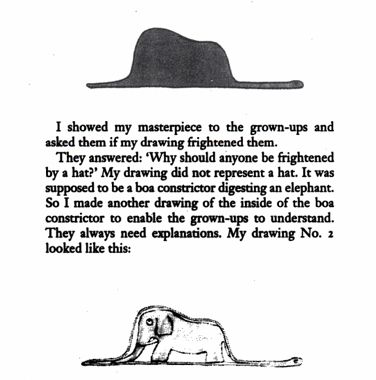

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince begins with an innocuous drawing. It’s a drawing that the adult narrator says he made as a six-year-old, and that the grown-ups around him construed as a hat. He’s, however, quick to point out that it was actually a drawing of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Later in life, as an adult the narrator is asked to draw a sheep by a stranger in the middle of the Sahara Desert: the little prince. After three failed attempts to impress the prince with realistic sketches, the narrator makes a simple box with three holes in it—and says the sheep is inside the box. “That is just what I wanted!” exclaims the little prince.

These drawings encapsulate a simple yet powerful message: inner experiences are more important than outer appearances. How then do we communicate our rich internal life through a limited external medium? Through a child’s imagination, perhaps. For the little prince, life on his tiny planet is like life in a small box with three pinholes, that’s why he can see the sheep inside the drawing. In fact, the novella is preoccupied with what cannot be seen but can be felt. For example, while the desert appears inhospitable, its wide expanse emerges as the starting point of the little prince’s personal growth and quest for truth—a meaning that is invisible on the surface.

Another instance in the novella that forces us to see beyond the surface is when the prince laments about his rose. The prince was fond of his rose due to its presumed uniqueness—he thought that such a thing would not be found on any other planet. But when he arrives on Earth, he is appalled to see that there are plenty of roses here; his rose is not at all unique. This is when the fox tells the prince, it is not the appearance that makes the rose exceptional but what it means to him—it’s their connection that makes his rose distinctive. At this point, it is evident that this fable-like story about a prince, his planet, and his rose is much more than meets the eye. Go beyond the surface, and there’s a wealth of meaning to be found.

While Exupéry’s simple story explores our profound relationship with the universe, the nonsensical world of Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland presents a higher form of sense. It is a parable of innocence and courage delivered with sparkling wordplay and anarchic humour. Down the rabbit hole lies a world where logic is suspended—only in this world is Alice able to make out her identity. The chaos of the Mad Hatter’s tea party becomes a critique of the Victorian era’s nobles, who were ignorant of ground realities. The Cheshire Cat defends the realness of Wonderland by posing a profound question: what is reality? And the clocks in the Wonderland defy the usual passage of time to show that time is a malleable construct.

With its surreal world-building, the book poses many philosophical questions. Carroll’s manipulation of language makes you question your perception of reality. He continues this search for truth in the sequel, Through the Looking Glass, where Alice experiences a world of twisted words, portmanteaus, and the absurdity of Humpty Dumpty.

Through their imaginary worlds, these three books offer insights into reality and our limited perception of it. They also offer us a way out of the cages of logic we build for ourselves as we grow up. After all, it is the innocence and ‘nonsense’ of children’s books that make us believe in the absolute freedom to live our lives and fulfil our desires. Perhaps they warrant a re-read in our adulthood.

Related: Sylvia Plath’s Drawings: The Lesser-Known Art of a Famous Writer