It is not ironic that Gobind reminds us of the tenth and last Sikh warrior, the philosopher and poet Guru Gobind Singh. Harinder S. Sikka’s brilliantly crafted narrative about an INS officer, Gobind, born in an impoverished neighborhood in the hinterlands of Bihar, turns into a tale of unanticipated valor, yearning in misery, and a triumphant plethora of audacious fearlessness. Against all preconceived notions, the novel refuses to be bogged down by and rejects the weight of nationalistic revelries, upholding the ideals of human empathy in the most unexpected registers instead, as seen in his previous works, Calling Sehmat and Vichhoda.

The story centres around protagonist Gobind, a poor lad who was never destined to move beyond his dire neighbourhood. The context of his father, Ranjit Singh’s efforts at uplifting his family out of their undulating circumstance supplements the protagonist’s awe-inspiring bildungsroman, especially as Gobind proudly scores a perfect mark in his school-passing test. The penury of his household compelled him to work at an early age. But Gobind’s adolescent ambition of aiding his father soon takes a tragic turn. While helping the landlord, Bihari Lal, take care of the oxen, Gobind’s soporific lifestyle moves towards isolation. Meera, Bihari Lal’s daughter, shook all possible equilibrium in Gobind’s life. Diving within the contours of enchanting euphoria, they were separated from each other’s love, never to return, unwittingly embodying the words of mystic poet Meerabai– ‘this separation is a bridge for our togetherness.’

The compromise in the beginning is always an usher, a push for the missing silver line in the cloud.

Gobind’s trajectory is one of uprooting oneself from the belittling muddles of casteism, and yet is a testament to the never-ending cycle of proving and disproving oneself. Bihari Lal’s late realizations about his daughter’s simple wishes and the consoling words of a kind-hearted superintendent in the Navy are both crucial examples of inalienable humanity. Their regret and emotional upheaval are as unexpected as they are refreshing, offering depth to their masculine performances. The narrative tells us about the principle subtlety within these men who work within the stifling climate of agrarian apparatuses.

Much like them but also different, Gobind is a man of principles. He is soft, yet firm. The absence of a genset in the new submarine and its replacement with a decommissioned one from the old submarine Sindhkosh, infuriated his ideals and disillusioned him about the premises of the Russian safety operations. He was aware that the use of second-hand instruments would only put millions at risk. This challenge kick-started his life at the Navy bloc. Amidst the self-alienating system of ploy, the protagonist could only attempt to fight. And fight he did.

What is intriguing about the protagonist’s story, specifically within the context of the cyclical life he seemingly leads, is the sheer amount of coincidence and repetition that seems to occur, slightly reminiscent of Nietszche’s theory of eternal return. This is specifically evident in Gobind’s interaction with Taraa, a near-resurrection of Meera and his future partner in Russia. It is perhaps this very thought that compels Muthu, his best friend, to ask, ‘But why does it seem to me that you both have known each other for decades?’

The tale is a mysterious enormity of emotions, tribulations, endurance and prowess. In the novel’s penultimate section, the reader encounters the spellbinding story about Taraa’s mother as well as details of their life in Russia. Taking refuge in the religious dispositions of Hinduism, she augments the beauty of amalgamation and fraternity. Even in Leningrad, a land where Russians are devoted to their motherland, it is the minority Hindu population of 0.1% that goes on to make an impact on Taraa’s family. The secular peace and an overtly enthusiastic juxtaposition of Hindu temples alongside the Russian Orthodox Church come as a serene addition to the narrative. Resembling Gobind’s spiritual mother Amrita, Taraa brings renewed intent in her genuine praise for poet Tulsidas – ‘the one who brings good and removes evil, he is Dashrath Nandan Shri Ram, may he bless me.’

One cannot judge a story for its outlook on life. Rather, one ought to look into the behemoth obstructions intimidating the character’s advancement. Even though Gobind excelled in the navy, being posted in the frontline warship frigate in Bombay, the rising sun and the hard-hitting waves on deck were all searching for his long-lost Meera. It is the genius of Sikka’s gruelling hauntology that enthrals slow-moving melancholia within the fateful success of Gobind, a brave soldier, a public servant, and a lover.

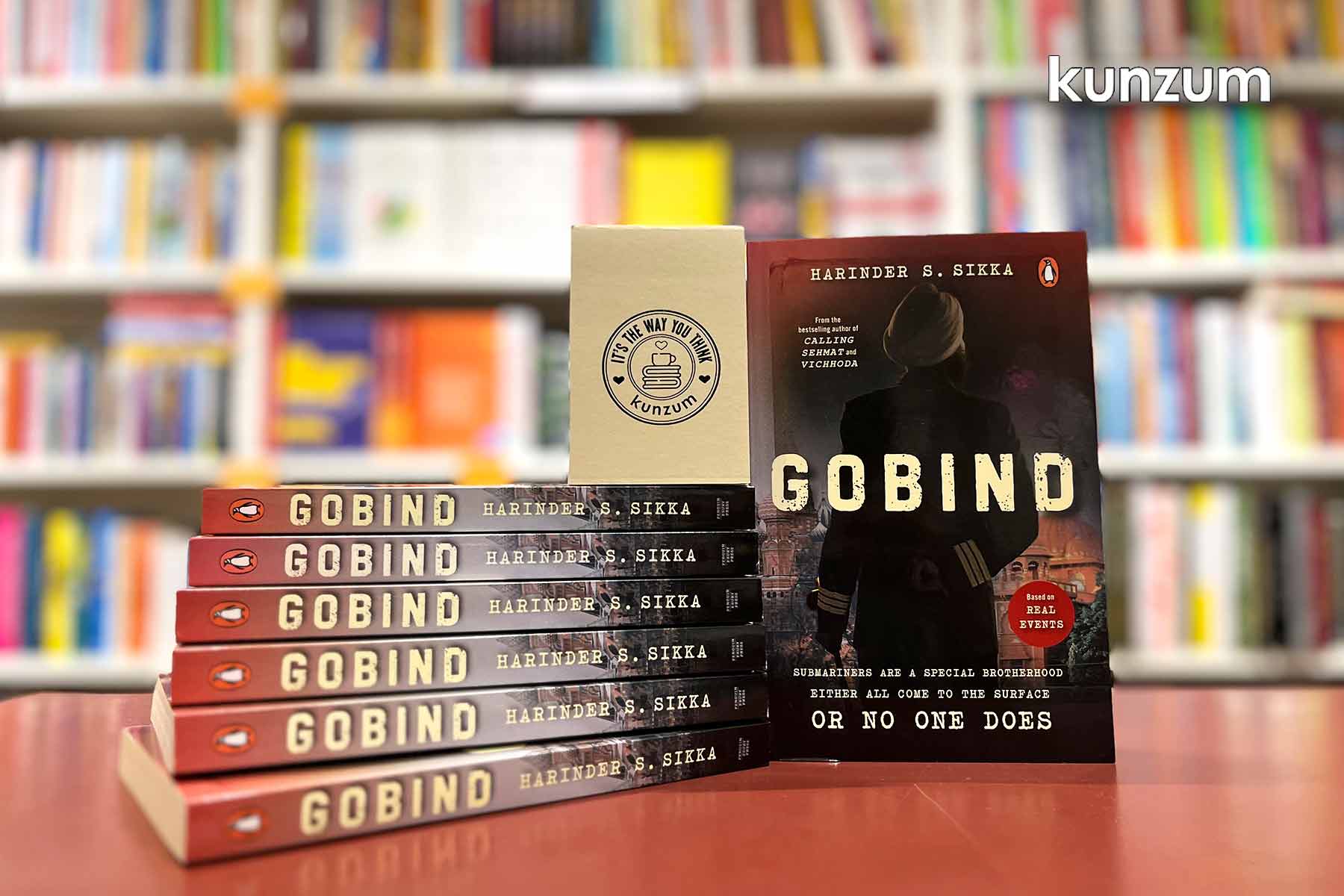

Pick up Harinder S. Sikka’s “Gobind” at Kunzum store or WhatsApp +91.8800200280 to order. Buy the book(s) and the coffee’s on us.

About the Author

Pritha Banerjee has completed her Masters in English Language & Literature from the University of Delhi. She was the recipient of the National Essay-writing Award from the SREI Foundation in 2014. Currently acting as a writer and translator for the Sankrityayan-Kosambi Study Circle, her latest publications include articles in ‘South Asian Women’s Narratives: Literatures of Their Own’ by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, FIPRESCI India, Muse India, Pashyantee: A Bilingual Journal, and Anustup Prakashani. Her upcoming translation of Rahul Sankrityayan’s ‘Dimaagi Gulaami’ is to be published by LeftWord Books. Find her on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook!