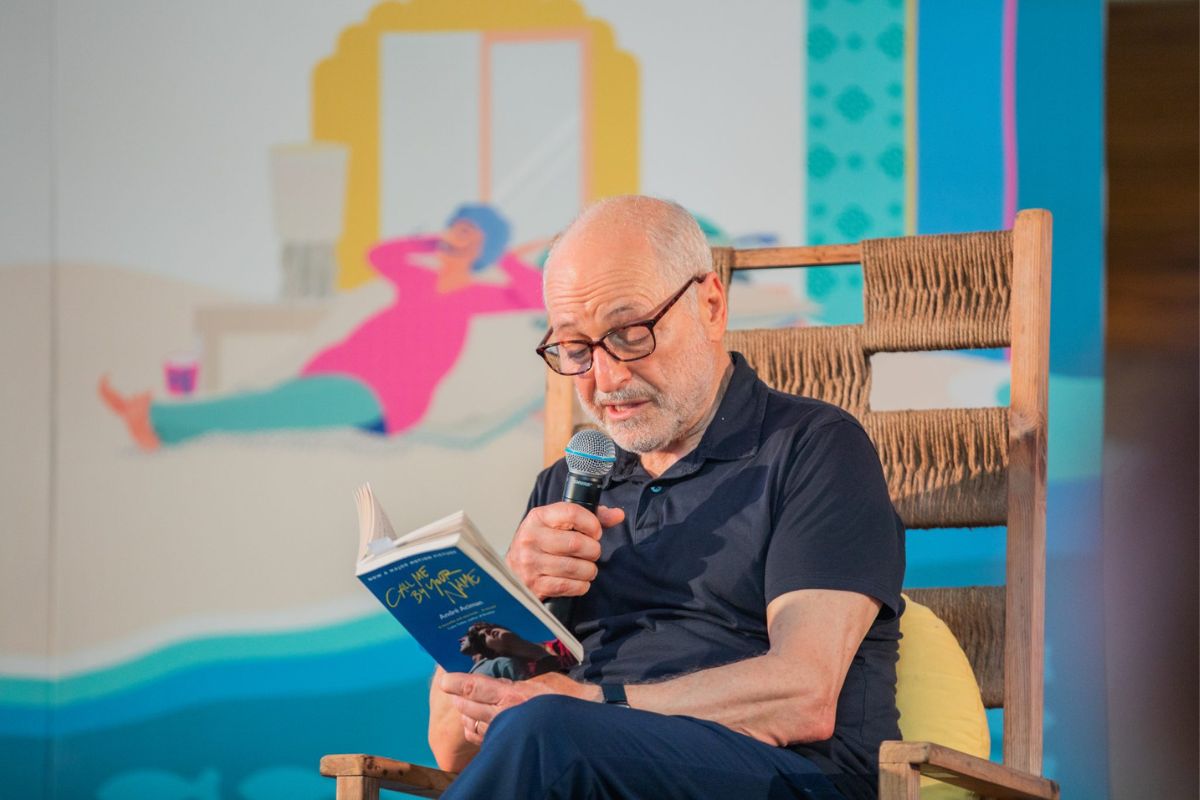

The bestselling author of books like Call Me By Your Name, Find Me, and, more recently, Homo Irrealis, André Aciman speaks with Sumeet Keswani about his most popular novels, writing about desire and shame, crafting gender-fluid characters, his literary inspirations and next book!

When I first met André Aciman, I was a starry-eyed journalist hesitatingly approaching a celebrity author for an interview. But over the next few days of a literal festival, and beyond, we became friends who shared many hearty meals and laughs together. He patiently listened to me describe my novel-in-progress and generously offered his advice, while I learnt about his life journey across countries, refined reading taste, and favourite type of Scotch. Here’s a distillation of many freewheeling conversations with the modern master.

The Standout Novels

What makes your two most popular books, Call Me By Your Name and Find Me, stand out from the rest of your work?

André Aciman: I don’t think they stand out that much, to be honest. But let us say they do—[it would be] in one respect. All three, including Enigma Variations, tend to be about human motivations and about how one human being examines another. I’m not interested in just the psychology of the character, which can become almost Freudian, but I’m always interested in the analytical aspect of the characters. What makes a person say, feel, or do something? How do they see themselves, and how do we see it? This has always been my fundamental understanding. That’s why I don’t like Tolstoy, whom I consider superficial. And Dostoevsky is almost like the summit of the investigation of the psyche of a character.

Are your characters based on people you know?

André Aciman: Most of it is a projection. I think I am all my characters. I project what I think they will feel or say. I don’t allow myself to withhold what they are feeling. If I’m going into a woman character, for instance, I will go all the way—and see what she feels, what she doesn’t want to feel, and what she can’t help but feel.

So, would you say that André the person bleeds into all the characters André the writer creates?

André Aciman: Yes, even if it is a dog. I become the dog.

Why are most of your characters gender-fluid? Is this a conscious choice?

André Aciman: Most of the people I have met—including myself—slip out of themselves into other things—other beings, other religions, other nationalities, other genders. The borders that have been imposed on us are artificial. I’m not interested in a fanatic; I cannot write one—a person who believes one thing and totally disbelieves all others.

Your gender-fluid characters may come naturally to you. But they have become a matter of representation for the LGBTQIA+ community.

André Aciman: Yes, that’s exactly what has happened. But not because I had a mission statement or [even] knew that this would happen. Take the example of Oliver. Oliver is a character I never understood. Because he’s self-confident; he is who he is and he’s not going to change. I find him almost two-dimensional. Elio, on the other hand, has no structure, no identity. He becomes everybody around him. He is morphing from one person to another.

What made you write Oliver like that?

André Aciman: Because I was trying to understand him. I don’t desire him, but I was interested to know how someone can be so happy with themselves. I don’t understand him, so I approached him from different angles—how does he play cards, how does he treat women, how does he treat the father? He doesn’t change, he’s constantly sure of himself.

You sound like Elio describing Oliver!

André Aciman: Yes, exactly! I’m trying to understand who this person is.

Do you like/love him then, like Elio does?

André Aciman: Do I like him? I don’t know. I don’t like people who are sure of themselves; I envy them. But usually, after a few drinks, they confide in me and I realise they’re like everyone else—as unsure of themselves as everyone! This morning, I was talking about feeling ashamed. I think this is what differentiates me from so many people. I am so easily ashamed of who I am. I am very shameful, timid, pusillanimous; very hesitant about what I believe and therefore I don’t reach out to other people. That is definitely not who Oliver is. Whereas Elio is far bolder than I have ever been in my life (for e.g., when he says “I’m gonna come to your room tomorrow night.”) I will never make a pass at someone unless I am sure that they will respond positively.

You said these books don’t really stand out from your other work, so what made them so much more popular? Was it the movie adaptation?

André Aciman: Not necessarily. The movie helped a great deal, because it made me quite famous. But the books, in and of themselves, were already [well-known]. This is the part I don’t understand. I’ve said this before: I don’t understand how people have emotionally responded to the story. For me, the story did not have strong emotional content. It was more about brute, almost forceful, desire. We’ve all had desire for many people, and I was interested in examining the nature of that desire, how it compels us. Most people had never heard sexual insecurity described the way I have, that’s what made it stand out. They’re most bitten by the unrelenting study of what it is to desire someone and feel terrified of what one feels. The people who have responded most to my work have not necessarily been gay people, but young girls, who say, “I know exactly how this character feels!” Because they have experienced timidity, inhibition, fear. I don’t think many people have described these things as openly. They (the readers) think they were responding to the love, the father’s speech, etc.—all legitimate—but I think what they were [really] responding to was the openness with which Elio narrates his own inhibitions.

Past & Present

Which writers have most influenced your work?

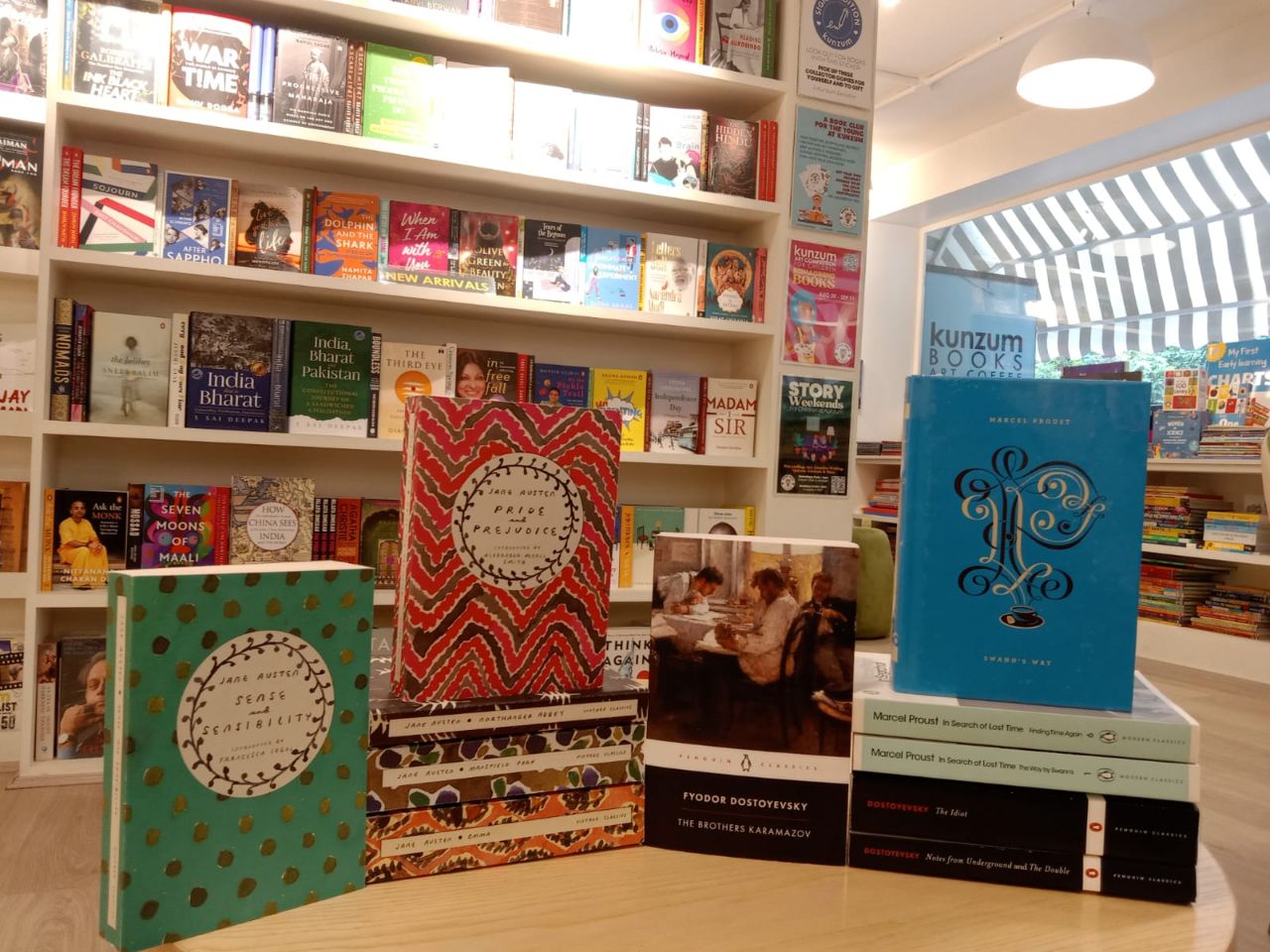

André Aciman: The very good ones. The first one who was totally compelling was Dostoyevsky. All his characters are troubled and twisted, and he’s not ashamed of telling you how twisted they are. I had never known that someone could have one aspect and then have the opposite one simultaneously. I love that Dostoevsky gave me the license to feel that way. Most writers will show you a totally dysfunctional person who has a disease that has a name. By and large, nobody wants to tell you how dysfunctional they are. The other one is Jane Austen. I love Austen very, very much. I teach Austen all the time. And finally, Proust. I don’t think I’ll ever be who I was before reading his books. You change once you read somebody this profound and this observant of the human condition. You begin to say, “I was superficial before. I cannot afford to be this way.”

Are you working on something now?

André Aciman: I’ve just finished a manuscript on my adolescent period in Italy. It’s a memoir—I arrived [in Italy] when I was 14 and left when I was 17. But I made it (the memoir) about one year. This was an eye-opening period for me. This is when you become a grown-up, and I didn’t even know it was happening.

When you write a memoir of adolescence in your 70s, are you worried about remembering things correctly? About changing the truth of your life?

André Aciman: When you’re writing about your own life, you move some of the furniture. Some things are irrelevant—they were relevant at the time but they don’t fit the narrative anymore. There are other things that may have belonged in some other time but they would really help the story, so you insert them. You try not to falsify the facts, but it’s the narration that takes over. So, I cannot say things [in the memoir] are exactly the way they happened—partly because I don’t remember how they were, and partly because when you look back you’re already altering the experience. So, when I was re-reading the manuscript, I would question things. Many times, I would call my brother and ask him—and he’d correct me. I did need that correction.

Related: Reading List: Filmmaker Onir Lists His Favourite Books

1 thought on “I Am All My Characters: André Aciman on Writing about Desire, Shame, Insecurity, and Gender Fluidity”