Amish Raj Mulmi set out to fill the vacuum of the knowledge regarding Chinese influence on Nepal by recording the lives of indigenous Nepali people. Curious about his research, Kunzum’s Ananya sat down with him to know more about his writing process. By Ananya

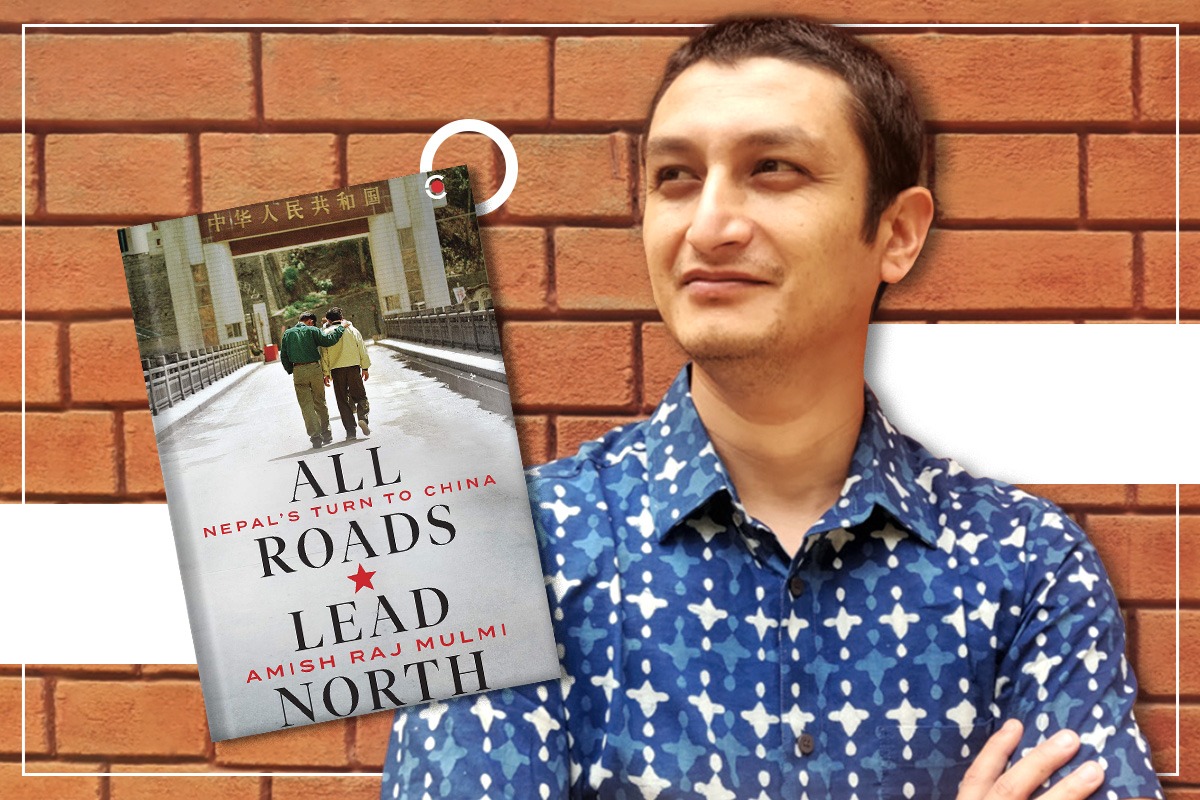

Author Amish Raj Mulmi’s new book All Roads Lead North: Nepal’s Turn to China investigates Nepal’s rich history of Nepal’s global engagement through its northern border, marked as it is by trade, cultural exchange, political manoeuvring, and occasional conflicts. The book was also selected as one of 2021’s best nonfiction books by The Guardian. Backed with 7th century Chinese traveler, 13th-century architects, untold stories of Tibetan guerrilla fighters, failed coup leaders and trans-Himalayan traders, poets and dozens of interviews, Mulmi crafted a masterpiece handbook for anyone who wants understand the depth of the Himalayas.

A Conversation with Amish Raj Mulmi

Kunzum: Your book All Roads Lead North explores the geopolitical relationship of Nepal with its two neighbours, China and India. Tell us more about when did the book start taking shape and what kind of research did it take to develop such a nuanced understanding of Nepal’s socio-cultural and political relations.

Amish Raj Mulmi: Everyone from Nepal loves going to the mountains, right? But going to the mountains and understanding the culture, understanding history and people is a different thing.

And once you start doing that, then you start developing a respect for the civilisations that have come up there. And then I also realised while living in Delhi that when you think about the Himalayas, you never think about their cultures. You mostly think about it from a different perspective. You’re basically preoccupied with the national aspects. And there’s also an eroticisation of the people. I realised the connections and the interconnections that existed in the human layer were a lot more intricate than they have ever been told. And I thought that their story needed to be told, which is why I started from a tale of the trade because that was the foundation of how people were interacting with each other.

The borders existed only in our minds. The larger question should have been, why hasn’t it been done till now? When you talk about the Himalayas, you mainly view it in terms of borders. Whether India dominates it versus China or the British explorers who have been roaming around as the moulders and supposedly mapping these areas for the world. However, their indigenous history goes unnoticed. How did the people living in the mountains imagine the mountains that are around them? How did the people imagine the world around them? That story hasn’t been told. I wanted to tell that story.

Kunzum: You mention in the book that Nepal has recently re-entered the geostrategic spotlight. In the context of this, why do you feel that it becomes imperative to look at Nepal as a significant country for those who want to understand South Asian politics?

Amish Raj Mulmi: Okay, so there are two parts. The first part is about South Asia. Recently, Yale was doing a South Asian Conference and all the speakers were talking about India only. So is South Asia only India? That is the first question. The second question: is South Asia considered then only through India’s purview? It is India-Pakistan, India- Bangladesh or India-Nepal.

Do the other countries and other communities in this region have to be hyphenated with India to become South Asian? And then the third part comes that Nepal, with its geographical position situated between the indigenous civilisation world and the Tibetan Buddhist civilisation world, forms part of both the Himalayan country as well as the country of the plains. So It is both: a South Asian civilisation as well as a Tibetan civilisation. But that part has never been told. That part has never been thought of and we always imagined Nepal as an extension of India. It’s always hyphenated with India and only then can Nepal’s reality or Nepal history can be told. I don’t think that’s necessarily true.

And as far as the geopolitical spotlight comes, what we have today is that you have China that has risen—you have the US that is contesting—and you have an India that is at loggerheads with China. And Nepal’s two neighbours are India and China. By that virtue alone, you have to start thinking of Nepal beyond just the regular satellite state.

Kunzum: In addition to being an author, you have also been a reputed journalist. Is there a difference in your writing when you write journalistic articles and a book which is a longer form of storytelling? If so, do you have advice for fellow writers on how to approach the same?

Amish Raj Mulmi: So the difference essentially is: how much material you want to put across in your piece. Like in short-form pieces, you don’t have the luxury of [different] nuances many times. Therefore you can not do the background content, the historical or political content. Which long form writing allows. Since I am more an editor than a journalist, my advice to fellow journalists who want to jump from short to long-form writing would be to emphasise on analysis. Start analysing the content you are writing and supplement it with adequate evidence that would make your argument stronger. Your primary and secondary research for a book is the key since you can take shortcuts in journalism, but in writing a book, there are no shortcuts.

Kunzum: Your interests and profile vary greatly, from being a journalist, editor and author to specialising in crime fiction, political nonfiction, travel writing and biographies. How do you strike a balance between all your profiles and reading interests?

It is only recently that I have become more specialised. I still read academic books, history and political non-fiction, but I am also indulging in crime fiction. It becomes a way to tap into a different way of thinking. When you read non-fiction, it is like you are teaching yourself something and with fiction it is more like you want to feel something. The idea that you need to get something out of reading a book is a very wrong way to approach reading itself. Reading because you simply just want to read—to get pleasure out of whatever it is that you read should be at the heart of the act of reading. It has to evoke something in you.

In the publishing industry especially—it is said that publishing at its heart is a business of passion. Unless you’re not passionate and driven by books, you can not work in it. The same goes for my other profiles. So for balance, the key is to enjoy what I do.

Kunzum: Can you recommend five books that one could read to deepen their knowledge of South Asian Pacific politics and geography?

Amish Raj Mulmi: Empire of the Indus by Alice Albinia, Tibet Tibet by Patrick French, Animal Intimacies by Radhika Govindrajan, Long Night of Storm by Indra Bahadur Rai and Forget Kathmandu by Manjushree Thapa.