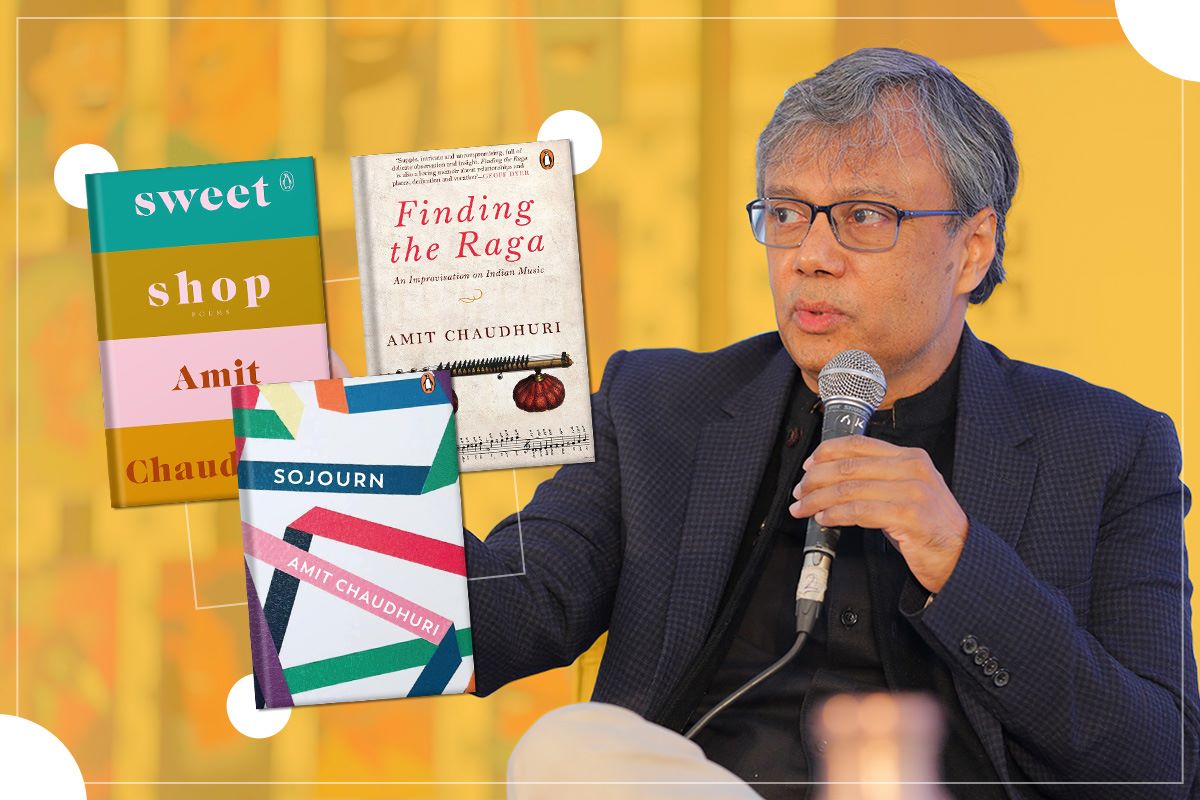

Amit Chaudhuri has many avatars―singer, novelist, critic, editor, professor, and poet! At the Jaipur Literature Festival 2023, we caught up with him to discuss his unique approach to writing, expression through Hindustani music, and affinity for the chaos of cities. By Paridhi Badgotri

While speaking with Amit Chaudhuri on his latest novel, Sojourn, at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2023, author Janice Pariat aptly described the book as a “moment” instead of a novel. Author of eight novels, Chaudhuri regularly experiments with form—his novels tend to be slim and are known to straddle multiple genres. Sojourn wanders around the city of Berlin and muses on the minute details of life. The novel is a collection of ordinary yet noteworthy moments; nothing overtly heroic or tragic happens in it, much like Chaudhuri’s other books, but therein lies the beauty of his work.

Curious about his creative process, we chatted with him to understand what goes behind his genre-defying books, his relationship with cities and music, and the representation of the self in his novels.

A Conversation with Amit Chaudhuri

Kunzum: There’s a new trending term in the publishing world today: auto-fiction. Do you think your work falls under this genre?

Amit Chaudhuri: Well, the term is new but I am not sure what auto-fiction is actually. The practice has been sort of going on for a long time, where authors bring themselves and their own names into stories. One example from the early 20th century is Colette, the French writer, and [another is] Manto. It’s a wonderful estranging device for these writers, that is, It’s happening to me, but the person writing is somebody else. Our conventional parameters of interpreting something as autobiography, biography, or fiction no longer seem important in the face of philosophical underpinnings of examining what the self is, like somebody wanting to die. And [it’s] a strange sense of hovering above oneself―being part of and yet not being part of it. I think this genre is a way of exploring that, [and] I think Annie Ernaux says something similar. People either confuse it for autobiography or confession―the person is telling us about the traumas in their lives or whatever. But there is a sense of detachment and even pleasure in describing the particular world that happens to this person, who happens to share the same name as the writer. In bhajans, they used to end with “kehat Kabir“―there’s a distance from the self. I don’t know if ‘auto-fiction’ is necessarily the best term to speak about works that are about the process of writing itself and also about this kind of estrangement—from not only one’s identity but the idea that if you write about yourself, you’re revealing something.

Kunzum: Do you think that not conforming to the rules of one particular genre/form gives you a sense of liberation?

Amit Chaudhuri: It’s about not being tied down to the conventional expectation that a work of fiction is something that’s made-up… On top of that, the offshoots of fiction declare their fictionality, fantasy, or magical realism, so to interrogate those expectations is to be free. Often, what we are interrogating are those parameters of realism that govern so much of what we write, whether it comes under the guise of self-definition or a “made-up” story, or a work of fantasy, or a work of magic realism. In a “made-up” story, you have, “Mr. So-and-so got up, he went to the balcony, he saw his friend, he went down, and then this happened.” In a fantasy, “Mr. So-and-so got up, and he went through the wall, then on the other side, there was a tiger.” In magic realism, “Mr. So-and-so got up, read the newspaper, a flying elephant went past, etc.” But the conventions of the syntax of the realist novel are being kept intact. It’s always one thing after another, then another; it’s like a sentence in Khadi Boli. A particular poet used to complain about Khadi Boli—how everything has to end with hai! What we want is to get out of this particular syntax―it doesn’t matter which route you take. As [Jacques] Derrida said, one of the best routes, whether in philosophy or in fiction, is autobiography, but not in the conventional sensibility. It is to just step out of this neutral kind of narrator presenting an imagined world—be free of the syntax of neutrality.

Kunzum: You don’t write heroic or tragic novels, instead focussing on the ordinary, workaday details of life. What informs this choice?

Amit Chaudhuri: Ordinary, because the world is of great interest to me. By the world, I don’t mean the stuff you read in newspapers but what is around you, and it’s not only the hero’s or heroine’s life that is important, it is the world. Often [when] talking about a hero’s/heroine’s life, a conventional novel marginalises life—by life, I mean, everything that is around me. I want that to have equal space as anything else, in fact that is where all the excitement lies for me. So, I want to bring it in further into the narrative. I am departing from a humanist approach to the novel, where the novel is always human-centred.

Kunzum: On one hand, you have parodied the Romantics’ sublime in your works, and on the other hand, you emphasise that one can find sublimity in modernity. Can you tell us how one can experience the sublime in the chaos of a city?

Amit Chaudhuri: Chaotic, for me, is anything that’s alive. I’m not saying life should be complete disorder… [but] orderliness, whether that’s orderliness you see in nature, which often is private property—beautifully manicured and owned by somebody—has a deadness about it. Cities, where everything is on some level private property and is owned and ordered by a particular version of the law, begin to replicate what is expected of them… Things need to break out of that―it has to be unexpected, surprising, in order to be of interest. So, I like certain parts of the city, I like certain parts of nature. So much is private property, so much is governed by a particular type of law. When there is too much silence, it’s because you are told not to honk your cars by a sign put by the law. I like that in India people are honking their horns. Chaos is at the heart of most literature itself. Throughout history, people are searching for those open and disorderly spaces. In our country, even the temples—not the new kind that are being built but the traditional ones—were open spaces; you would see a lot of people.

Kunzum: Many writers reclaim their precolonial land through the written word, but you reclaim your culture and self through music. Do you think classical music adds a different facet to the literary canon?

Amit Chaudhuri: Music is a form of thought, especially Hindustani classical music Khayal. In Finding the Raga, I have talked about forms of thoughts. These are forms of thought germane to the forms of thought that I’m exploring, and others have explored through novels and writing. Anything like post-enlightenment kind of writing, anything that’s supposed to exist only because it goes from one place to another, is then critiqued, and this is also true of the novel. And then the freedom of not going anywhere becomes a form of thinking; it is also pertinent to traditions like Khayal, Raag, which aren’t unfolding—to which delay is central. So, to me, all these are forms of thinking, and I’m exploring them and bringing them for whoever is interested to the discussion.

Kunzum: What are some of your book recommendations?

Amit Chaudhuri: I like so many books! I’ll give you some randomly: Elizabeth Bishop Collected Poems, [and] Dhusar Pandulipi by Jibanananda Das.

Kunzum: Which authors have been the biggest influences on your craft?

Amit Chaudhuri: I don’t think of it in terms of influence. It’s more about authors’ affinities with each other. [D.H.] Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers is one. It was not an influence, but it made me realise that the novel could be an act of homage―an act of tribute to the world. I did not want to sit down and write about characters. I wanted to pay homage to this contingency that we are alive now. And Lawrence made me realise that the novel can do that.