A book critic reflects on his discovery of Joan Didion and the impact one of her books had on his grieving process, while also trying to decipher what makes the prose tick. By Saurabh Sharma

One reaches out to one’s most trusted person in a crisis. In the wake of the pandemic, I turned to my all-time favourite Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me (Bloomsbury, 2017). I began rereading it for the umpteenth time. It begins with the photographer and writer Bill Hayes moving to New York after the death of his partner Steve. While the book will unfold differently for each reader, for me, it was an essential reading on grief, loss, and queerness.

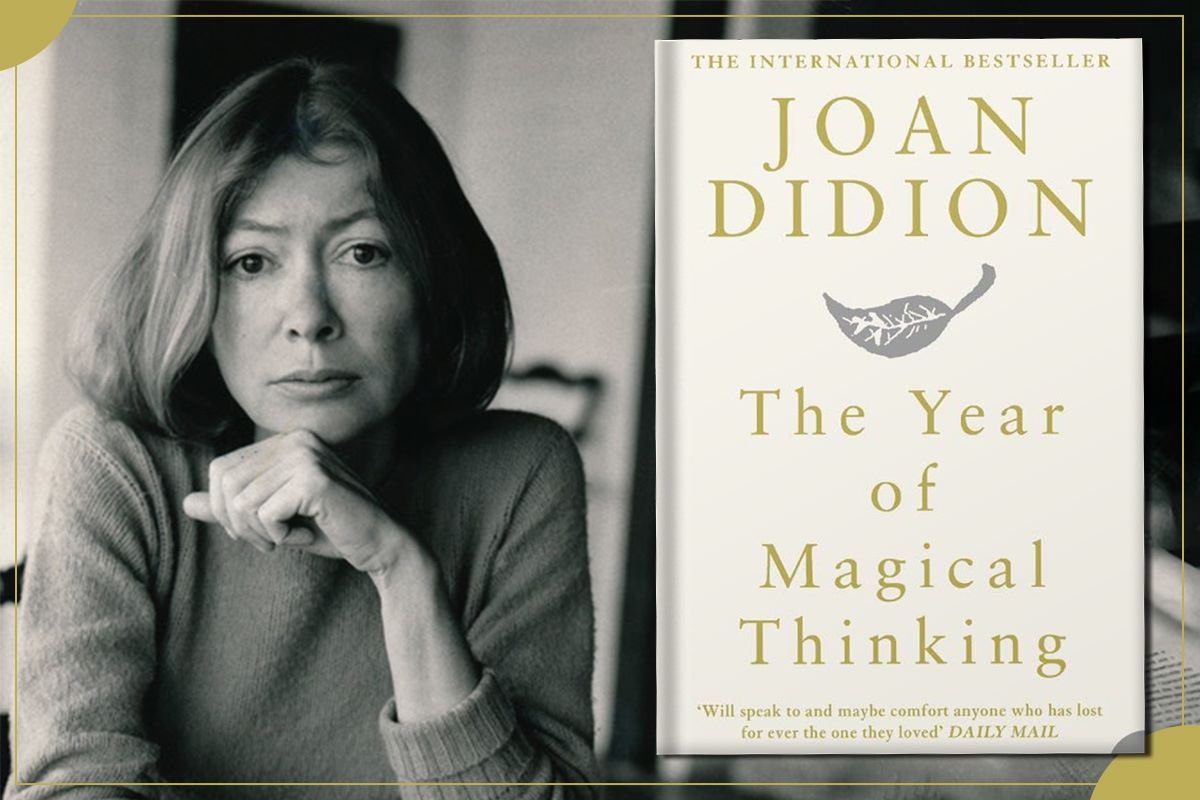

I gifted copies of Insomniac City to friends and potential dates, who now had extra time on their hands and wanted to “try reading.” It was at the same time that I started discussing books on Instagram. During one such discussion, a friend asked me if I had read Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (Vintage, 2005).

I wasn’t instantly convinced because the title made it sound like a self-help book. “By nonfiction, I mean narrative nonfiction like (Olivia) Laing’s works,” I wrote back, clarifying my reading preferences. In hindsight, I feel stupid. But, thankfully, I did get my copy of the Didion book, and reading the very first page I told myself: This isn’t going to be like anything you’ve read before.

A pioneering figure of the New Journalism era, Didion wrote immensely successful works like The White Album, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and Play It as It Lays, but it’s The Year of Magical Thinking—a memoir she wrote after the death of her husband John Gregory Dunne, a well-known writer, journalist, and screenwriter—that she’s most remembered for.

The book not only helped initiate or reintroduce grieving to people like me, but it also gave them a language to articulate it. For a writer, this book is a gift that keeps giving. Be it the repetition of impactful phrases (And then—gone.) to transferring guilt, blaming oneself, and confronting the inalienable feeling of loss, the book adroitly blends reporting and grieving.

In the first few chapters, Didion describes the delay incurred in getting urgent medical support for Dunne, her insistence on getting an autopsy done, and being called a “cool customer” by a social worker. The average reader may place significance on the emotional weight of these details. But a writer will assess it as a choice that the author exercised to offer a new paradigm of approaching loss.

Having said that, it’s hard to read a book like The Year of Magical Thinking with a strictly readerly or writerly focus. You cannot not remember your loss. Reading Didion for the first time in 2020, I was taken back to 2008. I asked myself: Had people who surrounded the Hyundai i10 that had had a head-on collision with a speeding truck on June 1, 2008, checked the pulse of the four men inside it? Or had they assumed that all of them were dead on the spot—as one newspaper reported it?

My father was in that car, which resembled a piece of crumbled paper in the image underneath the Hindi headline that read “Four Delhi-based Businessmen Died in a Car Accident.” I was in Aligarh at that time. My aunt and cousins knew what had happened. They didn’t break the news to me, perhaps thinking it’d be too much of a shock for a 15-year-old. They consoled me by saying that my father had had a bad accident and been hospitalised.

It’s just an accident.

He can’t talk right now, Saurabh!

Aren’t we going to meet him tomorrow?

Eat something, beta…

But the next day, I didn’t howl like the others when I saw his blood-stained body; I remember looking at this frail corpse and thinking it looked like someone else. I remember running a hand over his bier, to check. An uncle pulled me away, muttering a single word as if it were a secret: post-mortem.

Some things, we imagine, can only happen to others. No one, however, is an exception when it comes to death.

As I submit this piece, a friend has lost her father to cancer.

When I saw a notification of her message last night, I prepared myself for the inevitable, yet deep down I prayed it would be something else. I took note of all the possibilities:

- Maybe it’s about some book.

- Maybe she has finally read the copy of Insomniac City I sent her.

- Maybe she wants me to read and review a book.

- Maybe she needs me.

The last one didn’t occur to me — I knew she did.

Earlier that night, we were laughing with abandon in the meeting area of the hospital where her father was admitted, yet we all knew the fear that was written on our faces: He might not make it. What we were doing was avoiding the start of the grieving process. Didion was eating congee, I was doing algebra, and my friend was laughing with us, sharing memes and catching up on gossip.

“You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends,” this sentence from The Year of Magical Thinking never leaves me. For me, it happened in 2008. Then again in 2009. And for my friend, this morning. It seems I’ve been living in this continuum of grief, and only when I breathe my last will this end—because grieving is not a process one can begin and end anytime one pleases. It isn’t something you can subscribe and unsubscribe from. You’re not in control. This knowledge is necessary, but it comes late. Mine came from Didion. I know which book to gift my friend next.

Related: An Abundance of Hope Amid Tragedy: How John Green’s Books Transcend the Young-Adult Bookshelf