The world has worked overtime to distance its children from everything that’s wrong with it. Wars, for instance. News and literature about real life wars were a taboo for children, even young adults, except for a The Diary of a Young Girl occasionally thrown in. Recently, however, the plot has changed.

Now, the children’s bookshelves proudly host books that tell stories of ordinary people living in conflict zones like Syria, Afghanistan etc. Indian English fiction, too, swerved in this direction sometime back to bring us such books in the children’s and YA department.

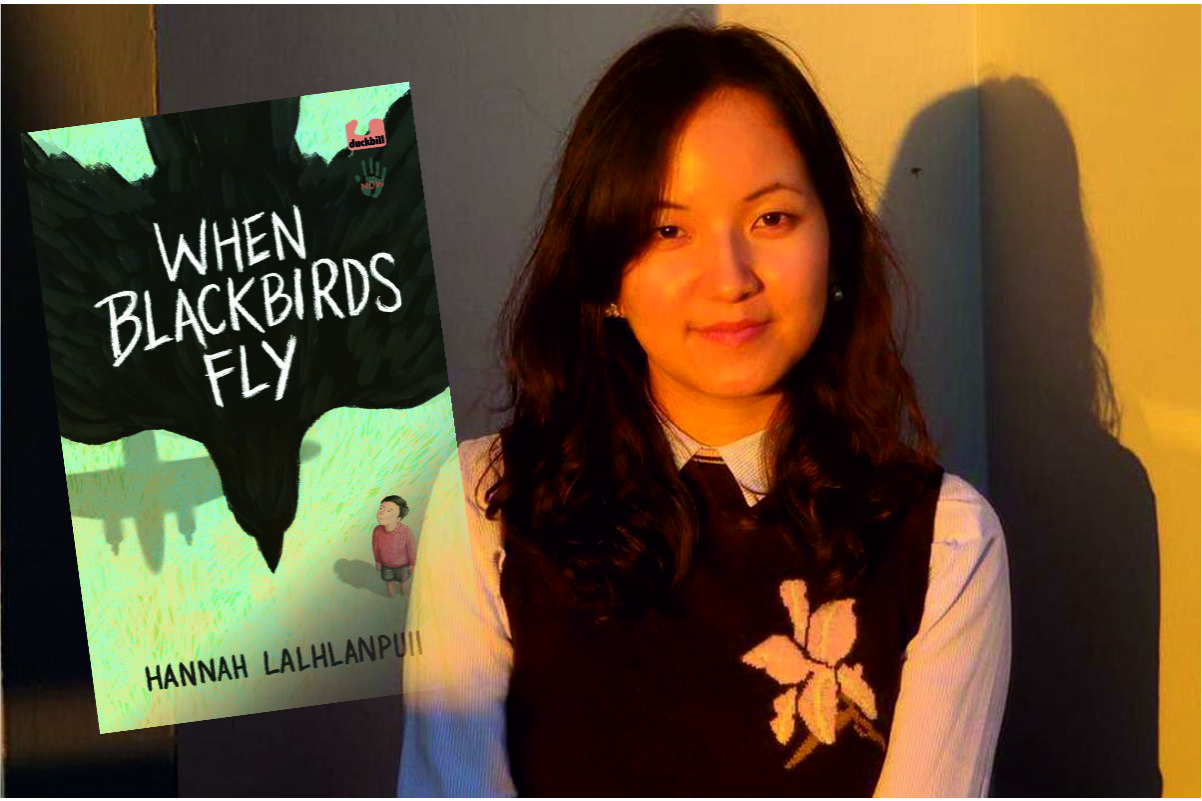

Hannah Lalhlanpuii’s debut book, When Blackbirds Fly, is one such breakthrough book set in Aizawl of the 1960s in the midst of a devastating event that changed the course of history in the region. The story is an inevitable piece of literature that fills a glaring gap in the children’s and YA rack.

“I wanted to tell the story of people like my mother whose traumatic experiences during the insurgency are silenced by political narratives,” says Hannah in an interview with Shruti Kohli, Managing Editor, Kunzum.

Shruti: When Blackbirds Fly is based on a true incident that occurred decades ago. To bring alive such an incident involves immense research. How did you research for your book? Feeding squirrels under that one tree, the ghee can (used to store cartridges), the pastor holding a stick with a white cloth knotted at the high end…these are subtle details belonging to another time. How did they all come together in your story?

Hannah: I conducted several interviews with people who would be in their early teens in the 1960s. I also went through historical archives, but it was mostly from the interviews that I was able to picture what life in Mizoram in the 1960s would be like, particularly the ones with the detailed and personal touches. For instance, I learnt from a friend’s grandfather that using ghee cans for storing cartridges was a common activity for schoolboys during that time.

I know that there are many who have similar stories like my mother’s and I was disappointed to see that Rambuai (Mizo term for insurgency) writings that we have are mostly political accounts.

Shruti: Writing period fiction comes with its own specific challenges. And when you have to narrate period fiction for children, it can require much more omission, and commission, mostly omission – violence, romantic relationships/acts/feelings etc. The protagonist’s feelings for Rini are quite intelligently presented without letting the strain (of omission) suffocate the appeal. How easy or difficult was it for you to keep the story ‘neat’ yet enticing?

Hannah: I tried as much as I could to put myself inside the head of the teenagers in my story, how they would think and perceive. Again, the interviews helped me a lot in this aspect because some of the interviewees are close family friends and I could freely ask them about their experiences and perspectives on almost everything during their teenage years, including romantic relationships.

Shruti: A very basic question. How did the idea of writing a story based on this incident come about?

Hannah: I grew up listening to my mother’s story about how she witnessed the killing of my grandfather by the soldiers during the insurgency and how my grandmother continued to raise her children and eventually developed mental illness because of the trauma she experienced during and after my grandfather’s death. I know that there are many who have similar stories like my mother’s and I was disappointed to see that Rambuai (Mizo term for insurgency) writings that we have are mostly political accounts. I wanted to tell the story of people like my mother whose traumatic experiences during the insurgency are silenced by political narratives.

Shruti: The plot of your book is set in another era. Yet, are you there somewhere in the story? Through some habits, mannerisms, like Rini touching the ends of her braids.

Hannah: You got me there. Friends, families and people who know me well often ask me whether Rini is based on my own character. I might have done it unconsciously.

Shruti: Although personally, I loved this ending. I did feel a lump rising in my throat at a few instances towards the end of the story. However, did you have alternate endings in mind?

Hannah: At first, I did feel that the ending might be too bleak for a children’s story. But nothing good came out of the insurgency and I wanted the story to be realistic from beginning to end.

Shruti: Are you working/do you plan to work on another book? Will it again be a children’s book? Have you thought of a subject/plot?

Hannah: Yes, I’m planning to write a novel based on my mother’s life which will focus on the psychological impact of the insurgency on the present generation. But it’s still just a rough idea.

I think a sense of historical awareness is important to bridge generational gaps.

Shruti: Would you like to leave a message for young readers and their parents?

Hannah: Listening to stories from my mother and the many old people I interviewed made me realize how important it is to know our history and the individual experiences of our parents and grandparents so that we can have a better understanding of how they think and feel. I think a sense of historical awareness is important to bridge generational gaps.